How the 2024 term fits into the history of the Roberts court

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

As Chief Justice John Roberts closes out his 20th term, the Supreme Court has entered a new phase – less defined by volatility and more by entrenched ideological structure. The 2024-25 term, while quieter than some expected, confirmed that the real story of the Roberts court is the steady narrowing and consolidation of control by a certain faction of the justices.

Over two decades, the court has moved from a shifting center – once held by Justice Anthony Kennedy – to a stable conservative supermajority that increasingly speaks through a few core voices. At the same time, the liberal justices have shifted away from a primary role of coalition-building to become more consistent dissenters, using their opinions less to persuade their colleagues and more to speak to the future.

From a swing court to a structured majority

In the first decade of the Roberts court, the ideological center was fluid. Kennedy often cast the decisive vote – joining liberals in cases like 2008’s Boumediene v. Bush and 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, while siding with conservatives in others, such as 2010’s Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

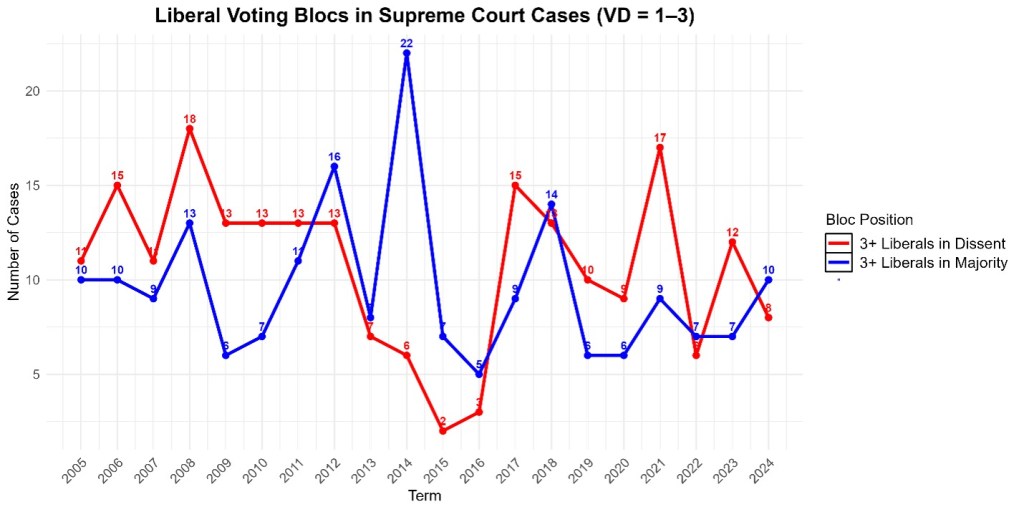

Roberts himself continued along his path as an occasional swing vote and also often as a restrained institutionalist, likely in an attempt to preserve the court’s legitimacy. Liberal justices could still win meaningful victories by building coalitions. Between 2005 and 2016, blocs of three or more liberal justices often formed part of the majority in significant cases, such as 2006’s Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and League of Latin American Citizens v. Perry, 2011’s Bullcoming v. New Mexico, and 2015’s King v. Burwell.

But that balance shifted with the appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch (2017), Brett Kavanaugh (2018), and Amy Coney Barrett (2020). Kennedy’s retirement and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death transformed the court into a 6–3 conservative majority. After that, compromise became unnecessary.

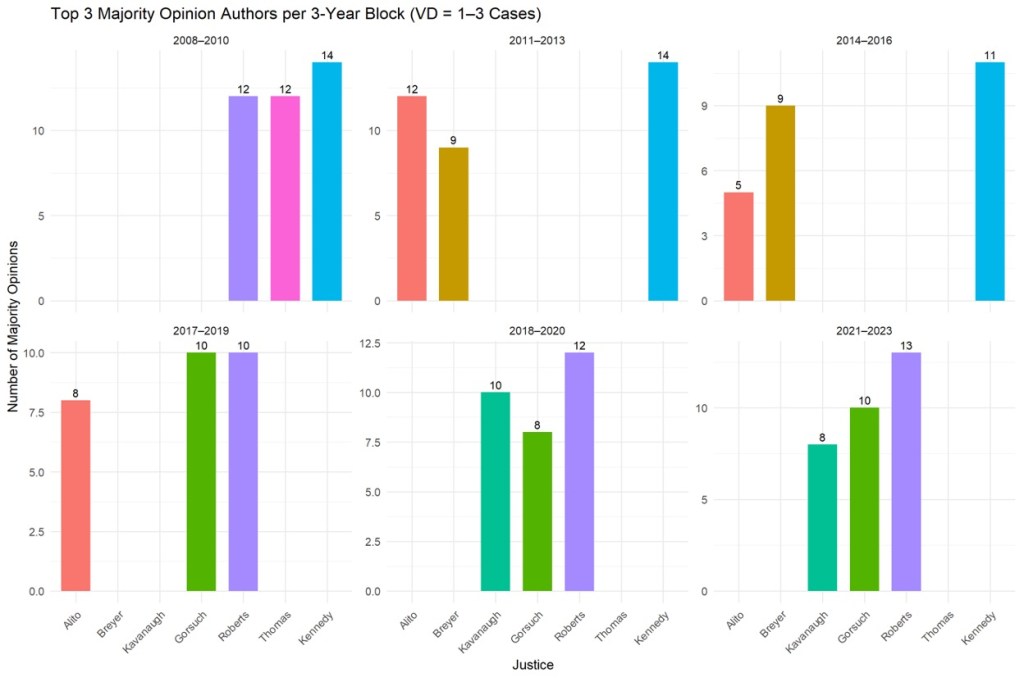

Note that the abbreviation I use below (“VD”) refers to vote difference between the majority and dissenting coalitions. VD 1-3 reflects cases with close votes that generally are either 5-4 (one vote difference) or 6-3 (three vote difference).

Liberal blocs were more often in the majority before 2018. Since then, they’ve been concentrated in dissent until the 2024-25 term, when the liberal bloc rebounded with 10 majorities in such cases and eight dissents.

It will be interesting to see what this means for the liberals. Is it a one-term blip on the radar or a sign of a small turning of the tide? But I do not want to overstate things: Several of the most highly publicized decisions, such as Trump v. CASA and Mahmoud v. Taylor, came down to a 6-3 vote along ideological lines.

The new majority core: Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett

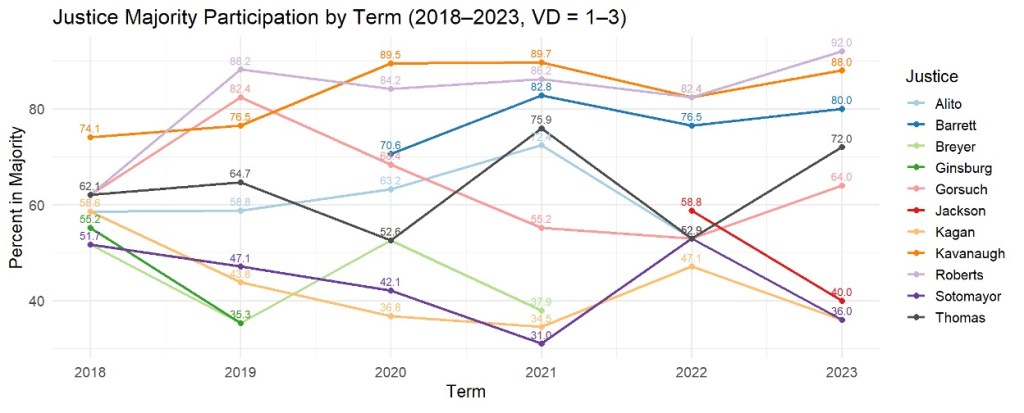

In the current court, power is not just about votes – it’s about voice. Over the past four terms, Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett have been the most frequent members of the majority in divided cases. They also often write the court’s opinions in high-impact disputes.

Specifically, during the 2024-25 term Roberts authored majorities term in United States v. Skrmetti, Lackey v. Stinnie, and A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools. Kavanaugh wrote Seven County Infrastructure v. Eagle County and Kennedy v. Braidwood Management. Barrett handled CASA, Medical Marijuana v. Hornand Advocate Christ Medical Center v. Kennedy. Their opinions are conservative in result, but carefully framed – often avoiding perceptible overreach, reinforcing precedent, and signaling stability. (Although Justice Samuel Alito wrote the court’s opinion in Mahmoud, that is undoubtedly an outlier to this trend.)

This trend is borne out statistically. As shown above, Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett have consistently appeared in the majority in closely divided cases since 2018. In the 2024 term, Roberts was in the majority 90% of the time in VD 1-3 cases, Kavanaugh was in the majority 80% of the time, and Barrett was in the majority 70% of the time.

Long-term trends: unanimity down, bloc discipline up

In earlier years of the Roberts court, the chief justice made consensus a hallmark. From 2010 to 2016, unanimous rulings often made up half of the court’s decisions or more. The high-water mark for this period — 64% — came in the 2013 term. Today, that number is falling slowly but perceptibly – down from 50% in 2022 to 44% in 2023 to 42% in the 2024-25 term.

But the drop in consensus hasn’t brought chaos. Conservative majorities are remarkably consistent. When they disagree internally, members of the conservative bloc often write concurring opinions instead of dissents. Gorsuch, for instance, frequently concurs to emphasize formalist or originalist principles. Justice Clarence Thomas does the same to signal future directions for the law.

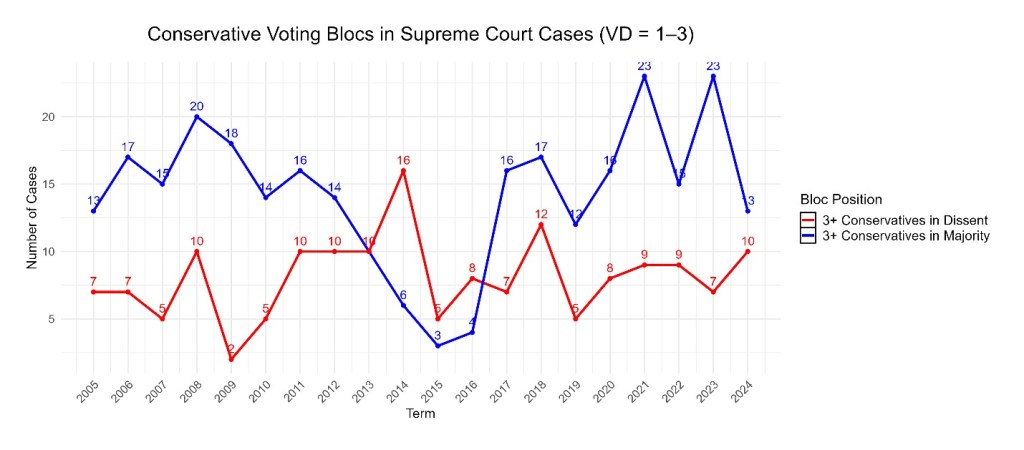

Since 2017, the conservative bloc mainly dominated majorities in closely divided cases, with numbers that far surpassed those of the liberal blocs until leveling out during the 2024-25 term as the liberals gained ground in such cases. While this might signal a decline in the ideological influence of the conservative bloc, as described earlier, the bloc still held together in many of the term’s most highly anticipated decisions.

Who’s writing – and what that tells us

Opinion authorship also matters. It shows not just who decides outcomes, but who defines doctrine.

Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Gorsuch routinely write the majority in close cases, as is evidenced in the graph below showing Roberts with 25 total opinions in VD 1-3 cases for the period spanning the 2018 through 2023 terms. Kavanaugh and Gorsuch were close behind with 18 apiece. Their styles shape how lower courts, agencies, and litigants read the law.

During the 2024-25 term, Roberts authored the most VD 1-3 majority opinions with four, while Gorsuch and Alito came next with three apiece. Barrett continued to develop a reputation for doctrinal clarity and coalition stability, authoring one of the most high-profile decisions of the term in Trump v. CASA. Meanwhile, Kavanaugh emerged as a central coalition writer, authoring more 6-3 majority opinions this past term than any other justice.

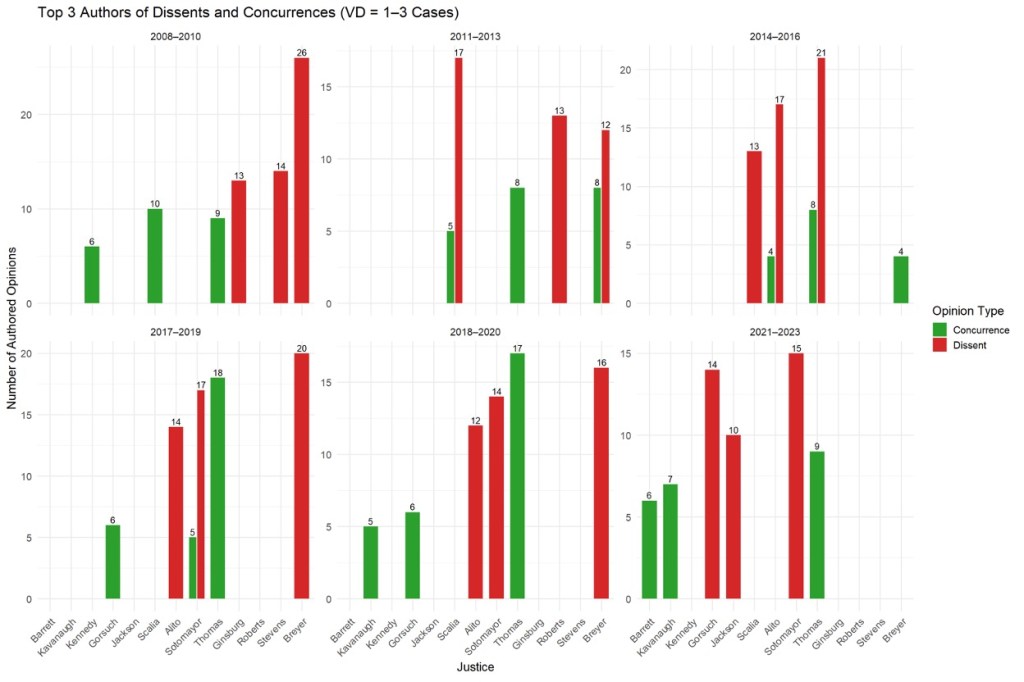

Dissents and concurrences offer a different kind of influence. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was the top dissent author this past term with 10, followed by the routinely prolific dissenter Thomas with nine. Thomas has reached high dissent marks across many different court compositions since the 2005 term, as shown in the graphs below. Thomas, Gorsuch, and Barrett led in concurrences, often laying down personal markers for future realignment.

In close vote cases since OT 2021, Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Jackson, and Gorsuch dominate the dissents. Thomas, Barrett, and Kavanaugh frequently write concurrences to clarify separate reasoning.

In the 2024-25 term, Thomas authored concurrences in five VD 1-3 decisions and dissented in seven. Justice Elena Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson all authored four dissents in VD 1-3 decisions, while Alito, Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Jackson all authored two concurrences in this set of decisions.

What comes next?

This term confirmed what many already sensed: The Roberts court has matured into a coalition-driven institution. There is no single swing vote, no rotating center. Instead, there is a stable conservative majority and a liberal bloc committed to articulating an alternative vision from dissent.

But several questions remain:

— Will concurrences increase, hinting at new future fractures?

— Will liberal dissents begin to shape how future justices or legislatures approach these rulings?

— As cases involving agency power, presidential immunity, and civil liberties return, will Roberts’ instinct for institutionalism slow the court – or help it pivot?

Structure over surprise

The story of the 2024–25 term is not just about who won. It’s about who spoke, who wrote, and how stable the court’s internal dynamics have become.

With Roberts at the center, and Kavanaugh and Barrett beside him as the second and third most frequent justices in the majority, the current majority is not only prevailing – it is defining the shape of American constitutional law. But the liberal justices, while often in dissent, especially in highly publicized decisions, are not silent. Their opinions are detailed, doctrinal, and aimed at the long game.

The U.S. Supreme Court Database provided vote data for terms prior to the past one (OT 2024).

A longer-form version of this piece can be found at Legalytics.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns