Diverse six-justice majority rejects broad reading of computer-fraud law

The Supreme Court’s decision on Thursday in Van Buren v. United States provides the court’s first serious look at one of the most important criminal statutes involving computer-related crime, the federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s opinion for a majority of six firmly rejected the broad reading of that statute that the Department of Justice has pressed in recent years.

Among other things, the CFAA criminalizes conduct that “exceeds authorized access” of a computer. Crucially, the statute defines that term as meaning “to access a computer with authorization and to use such access to obtain … information … that the accesser is not entitled so to obtain.” The question in Van Buren was whether users violate that statute by accessing information for improper purposes or instead whether users violate the statute only if they access information they were not entitled to obtain. In this case, for example, a Georgia police officer named Nathan Van Buren took a bribe to run a license-plate check. He was entitled to run license-plate checks, but not for illicit purposes. The lower courts upheld a conviction under the CFAA (because he was not entitled to check license-plate records for private purposes). The Supreme Court disagreed, adopting the narrower reading of the CFAA, under which it is a crime only if users access information they were not entitled to obtain.

For Barrett, the key to understanding the statute is that the user exceeds authorized access only by obtaining information “that the accesser is not entitled so to obtain” (my emphasis). She wholeheartedly accepts Van Buren’s view, quoting Black’s Law Dictionary, among others, for the proposition that the word “so” is “a term of reference that recalls ‘the same manner as has been stated.'” Under that reading, the key question under the statute is “whether one has the right, in ‘the same manner as has been stated,’ to obtain the relevant information.” Quoting directly from Van Buren’s brief, Barrett finds the answer to that question in the immediately preceding phrase in the statute: “the only manner of obtaining information already stated in the definitional provision is ‘via a computer [one] is otherwise authorized to access.'” In Barrett’s words, what the statute prohibits is obtaining “information one is not allowed to obtain by using a computer that he is authorized to access” (Barrett’s emphasis).

Barrett has no patience for the government’s reading, under which “so” refers generally to “the particular manner or circumstances in which” the information was obtained, so that it would violate the statute to obtain information violating “any ‘specifically and explicitly’ communicated limits on one’s right to access information.” Barrett starts by noting a practical oddity of that reading: that “an employee might lawfully pull information from Folder Y in the morning for a permissible purpose … but unlawfully pull the same information from Folder Y in the afternoon for a prohibited purpose.” The more serious problem, though, is that the government’s reading fails to account for “so”: “the relevant circumstance – the one rendering a person’s conduct illegal – is not identified earlier in the statute.” Barrett ridicules the government’s reading of “so” to “captur[e] any circumstance-based limit appearing anywhere – in the United States Code, a state statute, a private agreement, or anywhere else.”

Having parsed the statute and rejected the government’s reading, Barrett turns to the government’s “primary counterargument”: “that Van Buren’s reading renders the word ‘so’ superfluous,” because even without “so” the statute would criminalize using a computer to obtain information that the accesser was not entitled to obtain. Barrett gives content to “so” by pointing to a hypothetical case in which a person is entitled to obtain hard copies of files but is not entitled to obtain them from the computer. In that case, the crime would be obtaining from a computer information that the user was not entitled “so to obtain.” It would not be a crime to obtain the files by walking down the hall to them. But it would be a crime, under Barrett’s reading, to use a computer to obtain them. Barrett emphasizes that her reading “underscores that one kind of entitlement to information counts: the right to access the information by using a computer.”

Barrett also argues that the structure of the statute supports her reading, pointing to the two clauses that prohibit accessing a computer entirely “without authorization” and accessing a computer with authorization but “exceed[ing] authorized access.” Adopting Van Buren’s view, “[t]he ‘without authorization’ clause … protects computers themselves by targeting so-called outside hackers,” while “the ‘exceeds authorized access’ clause … provide[s] complementary protection for certain information within computers.” Barrett likes that “account of [the statute] because it treats the ‘without authorization’ and ‘exceeds authorized’ access’ clauses consistently.” She describes it as “a gates-up-or-down inquiry – one either can or cannot access a computer system, and one either can or cannot access certain areas within the system.” But the government’s rejected reading wouldn’t work that way, because it is only the “exceeds unauthorized access” clause that would “incorporate purpose-based limits contained in contracts and workplace policies.” Even the government did not contend that those external limits apply to “the threshold question whether someone uses a computer ‘without authorization.'” Barrett pointedly notes the lack of an explanation from the government as to “why the statute would prohibit accessing computer information, but not the computer itself, for an improper purpose.”

Finally, Barrett turns to a topic that dominated the amicus filings and much of the time at oral argument: the “breathtaking amount of commonplace computer activity” that the Government’s reading would criminalize. For Barrett, that reality “underscores the implausibility of the Government’s interpretation,” which provides (in words Justice Elena Kagan coined in an earlier case) “extra icing on a cake already frosted.” Barrett notes that extending the statute to “every violation of a computer-use policy” would make criminals of “millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens,” offering examples of such trivial conduct as “embellishing on online-dating profile” and “using a pseudonym on Facebook” – activities that violate website use restrictions and thus would fall within the government’s understanding of the CFAA.

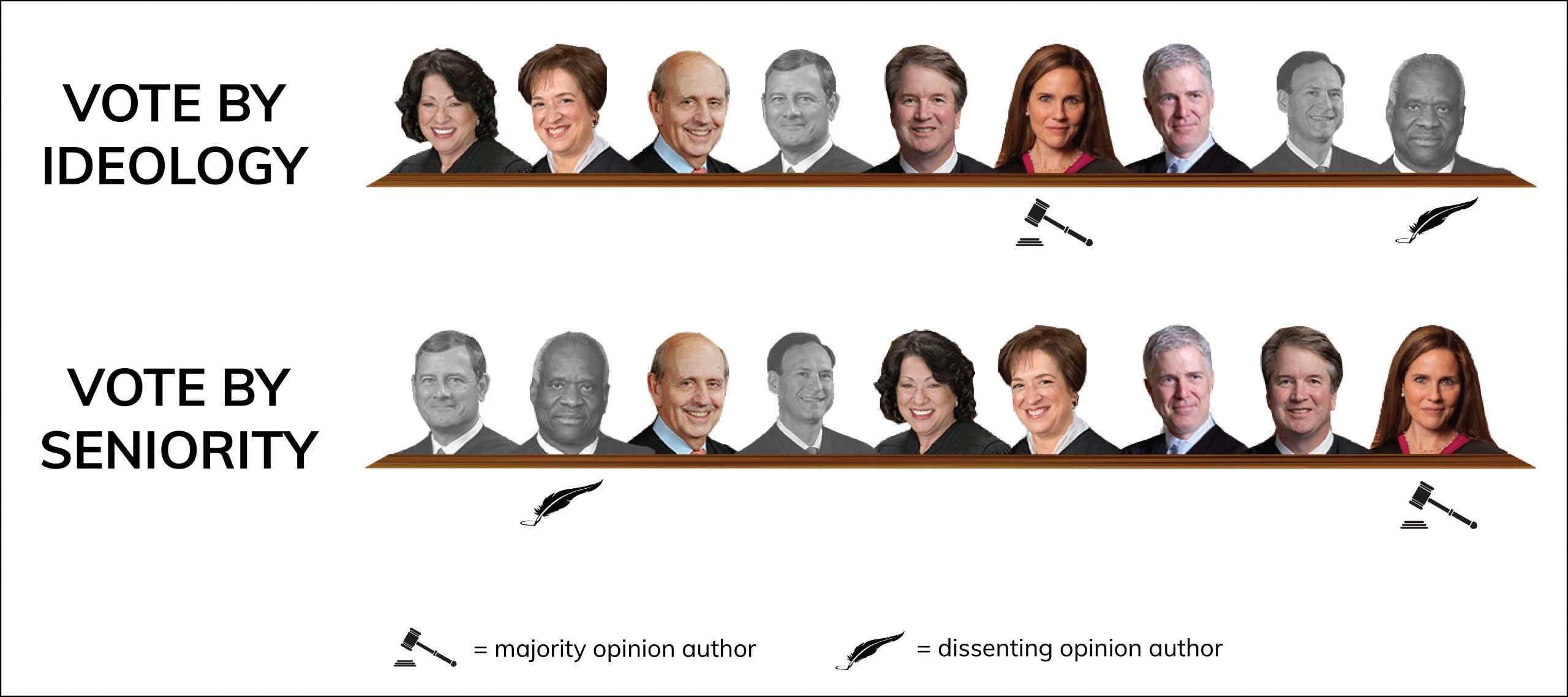

This already-lengthy article does not work through the details of all the arguments of the government and the dissenters that Barrett addresses, arguments that doubtless will consume scholars and lower courts for years to come. In the end, given the attention the case has gotten and the reactions at oral argument to the breadth of the government’s position, the final result here will surprise few informed observers. Probably the most notable aspect of the decision is the lineup, which includes in the majority Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, leaving only Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito to join the dissent of Justice Clarence Thomas.

Posted in Featured, Merits Cases

Cases: Van Buren v. United States