A “view” from the courtroom: The bridge-and-tunnel crowd

Politics is in the air at the Supreme Court today. Not the looming impeachment trial of President Donald Trump, which will be drawing Chief Justice John Roberts across the street to the Senate in a matter of days, but the “Bridgegate” affair out of New Jersey.

In 2013, three New Jersey officials schemed to close two of three access lanes normally dedicated to rush hour traffic from Fort Lee, N.J., onto the George Washington Bridge to New York City. (The other two lanes were shifted to join the eight used by interstate traffic approaching the toll plaza, a not insignificant fact when it comes to the legal theories in the case.)

The plan was payback against the Democratic mayor of Fort Lee for refusing to endorse New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie for reelection that year. The plan caused massive traffic headaches in Fort Lee for several days as well as longer-term political and legal fallout for all involved.

At the court today, it seems as if there is a dedicated lane at the security checkpoint for residents of New Jersey.

Two of the three officials involved in the scheme are here today: Bridget Anne Kelly, a former Christie aide, and William Baroni, a former deputy executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. While Kelly’s appeal of her conviction on federal fraud and conspiracy charges is the cert petition explicitly before the court, Baroni’s conviction came in the same trial and his lawyer has been granted argument time today.

The third official, former Port Authority aide David Wildstein, pleaded guilty in the federal case and testified for the government. He is now the editor of a website that covers New Jersey politics and is evidently busy covering the New Jersey legislature today.

There are, by my quick count, at least 30 Amtrak trains each weekday from northern New Jersey to Union Station in Washington. On Monday, Kelly boarded one to come to the argument and found Christie on the same train, headed for the same destination.

The two are not exactly on friendly terms. Kelly testified in her own defense that Christie was aware of the Fort Lee plan, but he has denied that and was not charged in the federal prosecution.

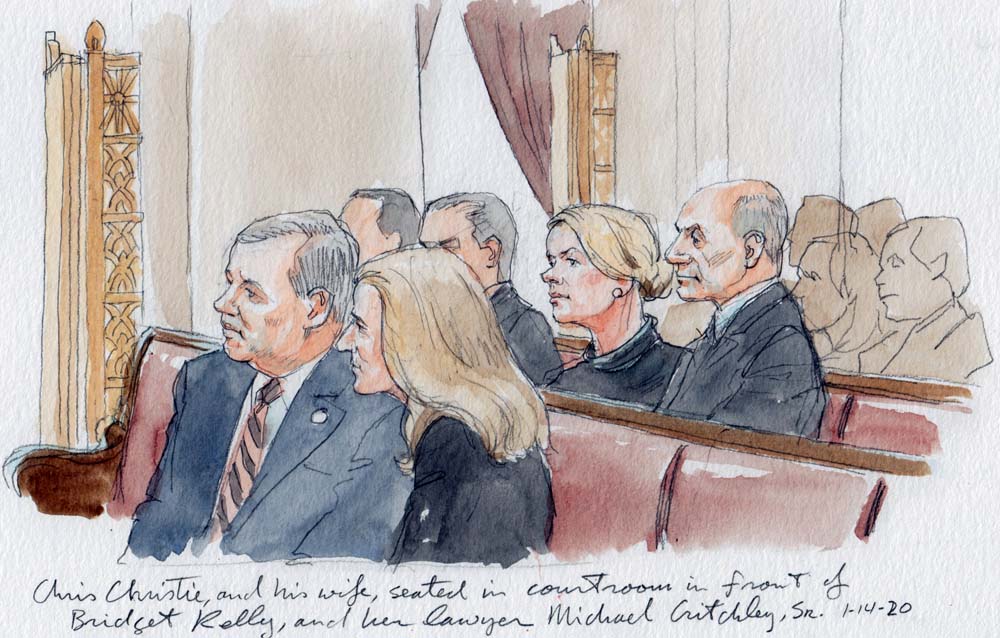

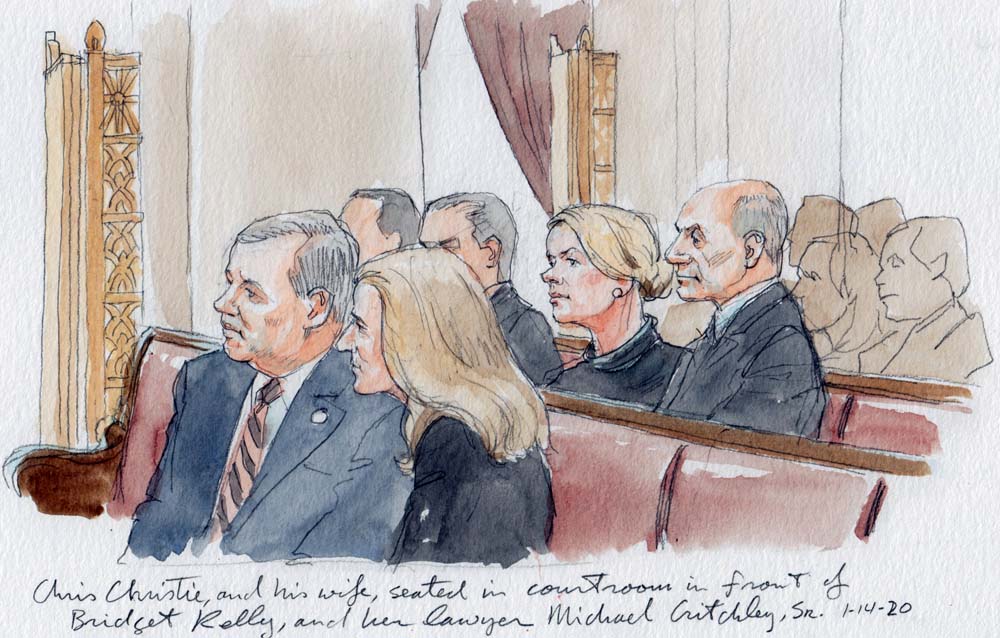

Kelly is seated in the second row of the public gallery with Michael Critchley Sr., her trial attorney. Soon after Kelly and Critchley take their seats, court personnel escort Christie and his wife, Mary Pat, to seats in the front row of the public section, directly in front of Kelly. (Later, addressing reporters on the plaza, Kelly will make clear that she and Christie did not speak to each other, on the train or in the courtroom. “It’s been a long six years,” Kelly will say. “I hope he has a harder time seeing me than I have seeing him.”)

The numerous New Jersey reporters who have come down for the argument seem astounded by Christie’s presence, suggesting the former governor, whose 2016 presidential bid was hampered if not undone by the Bridgegate scandal, is demonstrating quite a bit of chutzpah by showing up. Christie, now an ABC News political commentator, has probably never been accused of lacking that trait.

Meanwhile, Baroni is on the opposite side of the public gallery, in the third row. He will tilt his head to get a better view and maintain a serious expression, as his name will be mentioned about three times as often as Kelly’s.

Amy Howe has this blog’s main account of the argument. Jacob Roth, Kelly’s lawyer, stresses that “the government is trying to use the open-ended federal fraud statutes to enforce honest government at the state and local levels. Its theory this time is that the defendants committed property fraud by reallocating two traffic lanes from one public road to another without disclosing their real political reason for doing so.”

“This theory turns the integrity of every official action at every level of government into a potential federal fraud investigation,” he adds during his 20 minutes of time. Roth gets some intense questioning, but he manages to squeeze in a point about the unseemliness of the whole affair.

“I’m not trying to suggest that this is okay. Okay?” Roth says. “We don’t want public officials acting for personal reasons. We don’t want them acting necessarily for partisan or political reasons. But what I’m saying is the remedy for that is not the federal property fraud statutes. We have certainly political remedies that … had pretty substantial repercussions here.”

Michael Levy has 10 minutes to argue for Baroni. It turns out he and Baroni attended law school together at the University of Virginia.

One of Levy’s main points is that the government proved that Baroni, despite nominally being the No. 2 official at the Port Authority, was the co-head of the agency and had the authority to shift traffic lanes. That undercuts Baroni’s conviction, Levy says.

Trial testimony showed that “within the Port Authority structure, the deputy executive director and the executive director had a 50/50 split in terms of power sharing; that the deputy executive director was not the Number 2 position within the Port Authority,” Levy says.

This appears to have troublesome implications to Justice Samuel Alito, a native of Trenton and the former U.S. attorney for New Jersey.

“The arrangement is always that there’s a New York representative who’s the executive director and the New Jersey representative who’s the deputy, is that right?” Alito asks, and Levy confirms the arrangement.

“This is a bi-state agency,” Alito says. Why would New Jersey agree to an arrangement like that where its representative is always in the second seat, at least nominally? Just the big brother across the river.”

For the federal government, Deputy Solicitor General Eric Feigin defends the prosecutions. Solicitor General Noel Francisco is evidently recused from the case. As a private lawyer, he successfully represented former Virginia Gov. Robert McDonell in the last major public misconduct case before the court, and his former firm, Jones Day, represents Kelly.

“The defendants in this case committed fraud by telling a lie to take control over the physical access lanes to the George Washington Bridge and the employee resources necessary to realign them,” Feigin says. “Unless they lied about the existence of a Port Authority traffic study, none of them had the power to direct those resources and realign the lanes.”

The defendants “don’t get a free pass simply because their motive happened to be political,” he adds.

Feigin gets immediate pushback from Justice Stephen Breyer, who suggests the government’s theory would restore a broad definition of honest-services fraud that the court has trimmed back in recent cases.

Feigin says the case about a particular type of fraud that is indeed illegal — “commandeering fraud.”

“It is when the defendant tries to take over property that is in the hands of the victim and manage it as if it is his own property,” he says.

Justice Elena Kagan asks Feigin whether the case would have been the same if the shifting of traffic lanes had not caused massive backups in Fort Lee, or even “maybe improved” traffic.

Yes, he says. “It’s not about the effect although the effect was catastrophic and that was a reason why the prosecution was brought, because of the incredible danger in which they put the citizens and commuters of Fort Lee, but they would still have committed the same crime.”

After the argument, Kelly and her lawyers address the news media on the court’s plaza, as a light rain falls. She has been free on bond, with a 13-month prison sentence in the balance.

Baroni, surrounded by a large entourage of his lawyers and supporters, waits for Kelly and her pack to move away from the press area before descending the court’s steps to give an emotional statement. He had begun serving his 18-month sentence and was freed on bail after the Supreme Court granted Kelly’s cert petition.

“A year ago, I walked into federal prison, and I never dreamed that the Supreme Court of the United States would agree to hear our case,” Baroni says. He thanks Levy, his family members, friends here, friends in Ireland.

“There’s one other group I want to thank,” he says. “Those are the guys that I was in prison with. For every day I was there, [they] never let me stop believing, and never let me give up. Sometimes people forget them. But they are not forgotten today. So now we wait.”

Reporters wait a few more minutes in the rain for Christie, who is seldom shy about appearing before cameras. In fact, he rushed to appear before them after the oral argument in a New Jersey sports-betting case in 2018. But he doesn’t show. Maybe he has a train to catch.

Posted in What's Happening Now

Cases: Kelly v. United States