Empirical SCOTUS: Get ready for a confirmation battle more intense than most

Even though the Supreme Court is not in session, it is far from out of the news. With the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh, much of the conversation now concerns expectations for a fierce confirmation battle — possibly one of the most fierce we have ever seen. Notwithstanding the drama surrounding the failure of Judge Merrick Garland’s nomination, some speculate that because Justice Neil Gorsuch took the place of another conservative, Justice Antonin Scalia, the Democrats did not mount a significant struggle (or at least as significant as they could have) to combat that confirmation. Even so, the Republicans needed to enable and exercise the nuclear option to confirm Gorsuch, because they would not have succeeded under the old Senate rules. Now that the Republicans can put their mark on the Supreme Court for years to come with a justice more conservative than Justice Anthony Kennedy, many see the stakes as much higher. Here are a few reasons why.

Historical context

Supreme Court justice confirmation battles have taken many twists and turns in prior years and these have helped shape the type of confirmation hearing we can now expect to see. The hearings are (or at least were intended to be) one of the few opportunities for the general public to see and hear a current or prospective justice candidly answer questions.

The nature of these hearings changed with the Judge Robert Bork’s combative hearing in 1988. Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations during Clarence Thomas’ hearing in 1991 increased media attention to Supreme Court confirmations dramatically. Now with more aggressive vetting of potential nominees, nominees exercise increased caution in answering all questions.

Nominees now also posture themselves as purveyors of an objective standard of law, and avoid any reference to individual interpretation. The last several nominees avoided answering any questions about personal beliefs, usually deferring to the norm that they should not express any views on questions that they might hear on the court if confirmed. This tactic has proved generally successful. The only recent nominees not to be confirmed, Garland and Harriet Miers, never made it as far as the confirmation hearings.

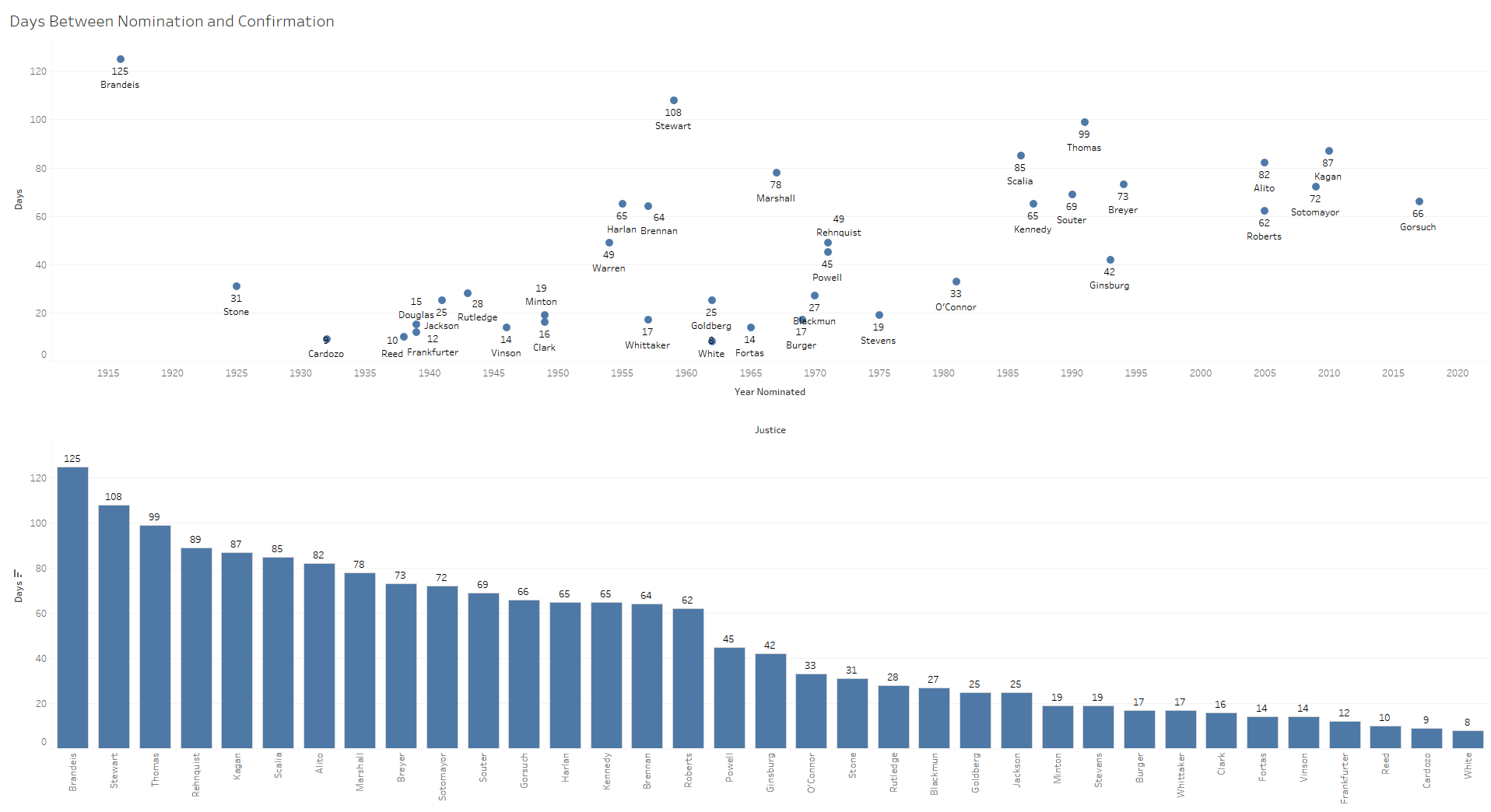

Garland’s nomination changed the terrain surrounding confirmation battles once again, as his nomination sat pending for 294 days, a modern record, before it expired in January 2017. The average time between a nomination and a final action in the Senate across the last several nominations was much closer to two months (N.B., the following figures were constructed with the aid of data from the Supreme Court Justices Database). Here are the times between nomination and confirmation for all confirmed nominees who had a hearing before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

None of these lengths of time compares to the amount Garland waited until his nomination finally expired without a confirmation hearing. With a Republican-controlled Senate and little chance of a credible Democratic opposition, we can likely expect Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings to fall in a more normal zone of around two months from the time of his nomination on July 9.

Justice Louis Brandeis, the nominee with the longest time between nomination and confirmation, was also the first to have a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Brandeis faced opposition from big business interests over concerns that he would push for unwanted reforms. Even though Brandeis had the longest delay, historically the time between a nomination and a confirmation vote has decreased for both successful and failed nominations.

Brandeis not only waited the longest before he was given a confirmation hearing, but he also had the longest confirmation hearing to date for a confirmed or unconfirmed nominee.

With a Republican-controlled Senate, we should not expect drawn-out hearings as in the case of some earlier nominations. Only about a quarter of the 162 Supreme Court nominations across time were unsuccessful, and fewer would have been so if the Senate voting rules for Supreme Court nominees were the same as they are today.

Since 1975, Bork was the only nominee who made it to the Senate hearing and was not confirmed. Going back to 1900, only 10 nominated individuals were not later confirmed. Across the history of the Supreme Court, the votes for nominees were overwhelmingly favorable. When organized from most net votes to fewest, the confirmation votes look as follows.

Failed nominations have been fairly evenly distributed over the years, although the bulk were in the court’s earlier history, as the following figure shows.

These figures suggest that modern nominees like Kavanaugh are more likely to be confirmed than their predecessors were and are also likely to wait longer to receive a confirmation hearing, and that modern hearings are and will be relatively short compared to those in the past. The newly enacted nuclear option providing for confirmation by a majority enhances the likelihood that nominations by presidents of the same party that controls the Senate will now succeed.

Where Kavanaugh fits in

Kavanaugh has gone through the confirmation process in the past as a nominee to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. He had one of the more controversial experiences with the ABA’s Standing Committee on the Judiciary, as he was initially given their highest ranking, which was later rescinded for a lesser ranking. Such moves by the ABA committee have led to some to say that it is guilty of partisan bias. This assertion may be tested by looking at recent nominees who have been given highly qualified or qualified evaluations by the ABA.

Whether or not the Republican nominees have been less qualified, they have borne the brunt of more negative ABA evaluations, which accords with Kavanaugh’s experience. With another ABA vote for Kavanaugh forthcoming, the potential evaluations have become an interesting source of speculation.

Confirmation success is related to a multitude of other factors along with ABA qualification ratings. Clusters of nominees, for instance, came from similar home states — most of them from New York. Nominees have not been equally successful, though, from all geographic locales.

Although all the many nominees from Virginia have been confirmed, the only justice from Virginia in the last 100 years was Justice Lewis Powell. Meanwhile, Kavanaugh is already in rarefied territory as a nominee born in Washington, D.C. Also, Bork is the only past nominee whose home state was the District of Columbia.

A partisan matter

We can also examine the success of nominees by their party affiliation. When nominees are divided by their last party affiliation, some interesting differences become apparent.

Although more Democrats have been nominated across the court’s history, a higher percentage of Republican nominees have been successful. If Kavanaugh is successful, he would add to this differential success of Republicans and Democrats. (As a side note, the only nominee with an independent party affiliation was Justice Felix Frankfurter.)

We can also look more granularly and focus on success by president. This not only accounts for party affiliation and the reputation of the nominee but also the reputation of the president and the relationship between the president and Senate.

Historically, George Washington had the most nominations for court candidates (having started out with the most open seats), while Franklin Roosevelt had the most successful nominations without any failures. President Donald Trump has one successful nomination so far with Gorsuch and his second pending with Kavanaugh.

With his second nomination to the court, Trump looks to reach the success level of his predecessors Presidents Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush, who both had two nominees confirmed and no failed nominations. Although there is little question about the Democrats’ resolve in stymieing this nominee, they have minimal leverage. With a Republican-controlled Senate, a simple majority the only requirement for success, and a Republican president making the nomination, the Democrats appear relatively powerless. Add to this the fact that even liberals within the legal community have had little resistance to offer, and it is unclear what type of credible fight the Democrats can make. Some signs hint at the public’s lukewarm perception of Kavanaugh, but in this highly polarized political environment, preventing Kavanaugh’s confirmation seems a tall if not impossible order.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.