Empirical SCOTUS: Slicing and dicing the court’s 2017 oral arguments (Corrected)

While the Supreme Court is lagging in releasing its decisions this term, the justices wrapped up hearing oral arguments almost a month ago. The justices heard 63 oral arguments between October 2017 and April 2018. Within that block of time, many expectations were reaffirmed and several new paths were blazed.

Aside from the accounts of those who sit in the Supreme Court’s pews, the only means we have to gauge interaction at oral argument is through the words spoken by the justices and advocates – either via audio recordings or written transcripts. Sometimes the justices’ questions conform to expectations about how they will vote in the case. Take the arguments in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. In one instance, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a likely vote for the state commission, engages in this pointed interaction with the cake artist’s attorney:

Contrastingly, Justice Samuel Alito, a likely vote for the cake artist, threw the same attorney a softball during this interaction:

Although the justices’ positions are sometimes predictable and their interactions occasionally hint at their positions on the merits, much is still left on the table after oral argument is complete. More to the point of this post, oral arguments occur in a sequence, with one or two per argument day over the course of a seven-month period. Certain insights can be gleaned from reading a transcript or by listening to an argument, but much of the material that can be used to make inferences about the justices’ positions or about case outcomes is not particularly glaring. Across 63 arguments this term, the justices and attorneys averaged 9,666 combined words spoken per argument.

Lay of the land

Activity at oral argument is not as straightforward as one might surmise. For instance, not all justices engage in every oral argument. For even the casual court-watcher, Justice Clarence Thomas’ lack of participation (he was silent at every oral argument this term) should not have come as a shock. Less bandied about is the fact that not all of the other justices choose to speak at each oral argument. Looking at the number of arguments with the justices’ active participation, we see that only three justices – Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sotomayor – spoke at every oral argument this term.

This baseline of participation affected the justices’ relative contributions to oral arguments this term. Several, but not all, of the instances of non-participation are products of recusals. These include one for Justice Elena Kagan (she recused herself from Jennings v. Rodriguez after oral argument), one for Justice Anthony Kennedy, and three for Justice Neil Gorsuch. All occurrences of non-participation for any reason are treated similarly in this post.

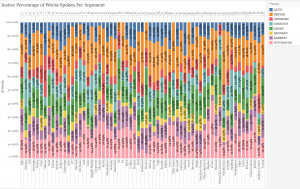

This justice-level participation can be broken down further into individual arguments. The following graph shows the justices’ relative contributions by percent to the total words spoken by all justices at each oral argument. The arguments are ordered chronologically by argument day.

Overt and subtle details about the justices’ participation are covered in this graph. Combining this with the previous graph, we can note that the one argument in which Kagan did not participate was Rubin v. Islamic Republic of Iran (a product of her recusal). We can also note that Justices Stephen Breyer and Sotomayor tend to speak the most. Even with their regularly high level of participation, these two justices were more dominant in some oral arguments than others. Breyer spoke nearly 40 percent of the words from all justices in WesternGeo LLC v. ION Geophysical Corp., while Sotomayor spoke over 42 percent of the words from all justices in Koons v. United States.

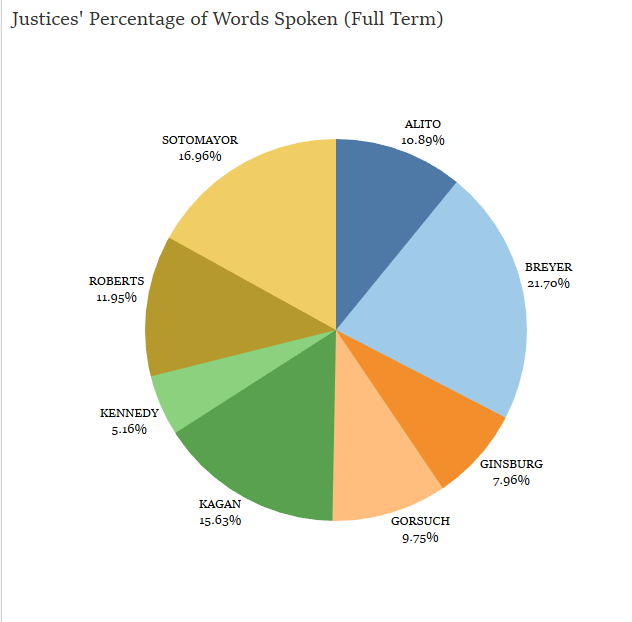

This leads to the breakdown of the justices’ relative participation across all oral arguments this term in the aggregate. The top two speakers have already been highlighted.

Kagan spoke the next most after Sotomayor, while the Supreme Court’s right-wing members (aside from the silent Thomas) each spoke a similar amount to one another this term. Kennedy and Ginsburg, traditionally two of the less vocal justices at oral argument, did not alter their behavior this term. Kennedy spoke the least, with just over five percent of the total words from all justices.

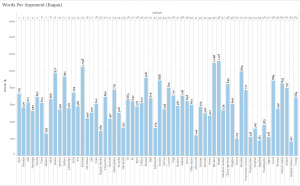

We can take a different vantage on the various actors’ contributions to oral argument by looking at the cumulative amount of speech in each individual argument as is shown in the figure below.

While at only the normal allotted time of one hour, the number of words spoken was at the high end in the Masterpiece Cakeshop and Carpenter v. United States cases, while it was minimized in cases at the opposite end of the spectrum like Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago and Rubin.

Several attorneys were repeat players across these 63 oral arguments. These attorneys are spotlighted below.

Private attorney Paul Clement participated in the most oral arguments, followed by government attorneys Jeffrey Wall and Malcolm Stewart. Even though individual attorneys only participated in a modicum of arguments across the term compared to the justices, some were able to contribute quite significantly in these limited instances.

When we look at the top speakers’ (justices and attorneys) cumulative words spoken across the term, we see that several attorneys are in the mix.

Clement, for example, spoke more words in his six arguments than Kennedy in his 58. Kannon Shanmugam, Jeffrey Fisher, Eric Feigin and Neal Katyal each made substantial contributions in three arguments apiece. Not far behind them follow Malcolm Stewart with his five arguments and Adam Unikowsky with his two.

Attorneys

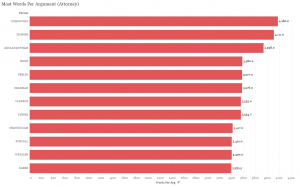

Examining the participation of attorneys in a bit more detail, we can gather more information about their involvement at the case level. Below are the attorneys who spoke the most words per argument.

Adam Unikowsky’s high level of involvement in the cases he argued is apparent from this figure as well as the one above it. Some of the other attorneys already mentioned, including Kannon Shanmugam and Jeffrey Fisher, made substantial word-based contributions at the case level. Others, like first-time arguer Stephen Vladeck, made strong impressions, as measured by the number of words they spoke, despite their lack of experience before the justices.

Looking at this question a bit differently, we can also order the advocates based on the greatest word contributions in terms of words spoken in individual arguments. This analysis is detailed below.

Of this list of attorneys’ participation, four attorneys had over 4,000 words spoken in an argument. These include Adam Unikowsky in Artis v. District of Columbia, Eric Feigin in Encino Motorcars v. Navarro, David Zimmer in Pereira v. Sessions and Adam Unikowsky again in Sveen v. Melin.

Although these attorneys were able to articulate a lot of substance during oral arguments, they did not all have equal opportunities to do so. Some made the most of fewer opportunities, while others provided curt responses across many turns talking. The breakdown of attorneys with the most speaking turns by argument is shown next.

Thomas Goldstein with his argument in Cyan Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund and Solicitor General Noel Francisco with his argument in Trump v. Hawaii far surpassed other attorneys in their total talking turns. Several of the attorneys with the most words in an argument also appear in this figure, including Neal Katyal with his argument in Trump v. Hawaii, Jeffrey Fisher with his argument in Currier v. Virginia and Adam Unikowsky with his argument in Sveen.

Justices

Unlike particular attorneys, Supreme Court justices are engaged in each oral argument over the course of the term. Even the reticent Thomas is often caught perusing briefs while on the bench. Still, not all justices are equally engaged and their type of engagement varies as well.

The first way to view the justices’ relative engagement is through their words per argument across all arguments in which they participated this term.

The lead speaker at oral arguments for the past several terms, Breyer, once again was the most active speaker by a large margin. Sotomayor and Kagan have also helped lead the way in terms of the justices’ speech over the past several terms. While Justice Antonin Scalia was not the most gregarious of justices at oral argument at least in terms of total word output, Gorsuch seems to be lagging behind Scalia’s model. Gorsuch was the justice to average the third fewest words per argument in which he participated.

Even when justices participate in oral arguments, they are occasionally minimalists. In 29 instances this term, justices spoke 100 words or fewer in an oral argument.

Not surprisingly given his low output across the entire term, Kennedy had the most such instances among the justices. Still, five other justices are also covered in this figure, and the only justice in this figure with just one instance of 100 words or fewer in an argument is Sotomayor. This goes to show that the justices (possibly with the exception of Breyer) put a disparate amount of energy into various oral arguments, and that Kennedy deliberately chooses when to engage.

The justices also cumulatively vary in their engagement from case to case. In certain oral arguments this term they had little to say across the board.

The justices as a unit spoke much less in Rubin and in Lamar, Archer & Coffrin, LLP v. Appling than they did in other oral arguments this term. Both of these cases were seen as less salient than some of the blockbusters like Masterpiece Cakeshop and Gill v. Whitford. It is possible that the justices as a whole modulate their involvement based on a variety of factors, including the perceived importance of cases.

When we look by contrast at the cases in which the justices as a whole engaged the most actively this term, we see cases that engendered the most public scrutiny toward the top of the list.

The justices, not surprisingly, spoke the most in Masterpiece Cakeshop — well more than in any other case this term. The argument in which they spoke the second most was the highly anticipated Fourth Amendment case of Carpenter v. U.S. Although this is not a clear indicator of case salience, this as well as the variation in justices’ speech in oral arguments across the term shows that they are not equally engaged in each case.

Of course, words spoken is not the only measure of justice engagement. Justices take a number of speaking opportunities in each oral argument and say varying amounts during each of these turns talking. Breyer often expounds lengthy hypotheticals during his turns while other justices engage in more pithy interactions with the attorneys. When we look at the average number of talking turns per oral argument across the term, we arrive at the following figure:

Sotomayor usurps the speaker role more than any of the other justices. Breyer takes the second most talking turns of the justices and yet speaks volumes more than any of the other justices. The justices aside from Thomas who speak the least — Ginsburg and Kennedy – also take the fewest speaking turns.

Breyer’s dominance in terms of total speech is immediately apparent when we look at the arguments in which the justices spoke the most this term. The threshold I set for this figure was at least 1,000 words in an argument.

Breyer alone had more arguments with at least 1,000 words than the rest of the justices combined. He also had the most words in an argument this term in the Ohio v. American Express case. Sotomayor had the second most words in an argument in Masterpiece Cakeshop.

The justices use their speaking opportunities differently. Some choose to ask more questions than others. (I use question marks as the marker for questions in this analysis.) The instances when justices asked 25 or more questions in an argument this term are shown in the next figure.

While Breyer had 25 or more questions in more arguments this term than any of the other justices, Gorsuch, Alito and Sotomayor each had several arguments with more than 25 questions as well. This is particularly interesting because although Sotomayor was one of the most active speakers this term based on the justices’ spoken word counts, Alito and Gorsuch were not.

The next set of figures dig deeper into the justices’ word-count participation on the individual case level. Each graph charts a justice’s unique behavior so that we can see when they chose to engage with the attorneys more and less often.

Beginning with the ever-enigmatic Kennedy, we can see signs of varied, yet often minimal, participation.

Kennedy spoke most at the Masterpiece Cakeshop oral argument, and also contributed a significant amount during arguments in Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Class v. United States and Carpenter. He had little to say in multiple arguments, with 12 words in District of Columbia v. Wesby, 26 in Pereira and 27 in both Abbott and National Association of Manufacturers v. Department of Defense.

Along with Kennedy, Ginsburg was also a minimalist in terms of the amount of speech she contributed across the term. Age may be a factor in the amount of engagement from both of these justices, who are the two oldest on the court. Ginsburg’s participation looks as follows:

Ginsburg reached the 1,000-word marker in one argument this term – Hall v. Hall, which interestingly was just about at the midpoint for arguments this term. She added over 800 words in Hamer. On the other end of the spectrum, she only spoke 31 words in the Abbott argument.

Kagan was much more actively involved in oral arguments than the previously mentioned justices.

Kagan had multiple arguments with over 1,000 words, including in Upper Skagit Indian Tribe v. Lundgren, in which she had a word count of 1,116. Even when Kagan spoke less, she had over 100 words per argument, so she was more active on a regular basis than Ginsburg or Kennedy.

Moving in the direction of the most active justices at oral argument, Sotomayor was regularly near the top in terms of words spoken.

The trajectory of Sotomayor’s speech pattern is notable as well. Sotomayor appeared to start out slowly and to increase her input into oral arguments through the first part of the term. After around the midpoint she spoke less once again, only to increase her words per argument a second time toward the Supreme Court’s final sitting of the term.

Breyer, while apparently never at a loss for words at oral argument, had variation of his own.

With 21 arguments – a third of the total arguments for the term — in which he spoke at least 1,000 words, Breyer often had more to say than any of the other justices. Still, Breyer spoke minimally (at least in a relative sense) in several cases during the term, including in Sessions v. Dimaya, which not only was one of the more important cases of the term, but also divided the justices, leading to a 5-4 split decision. Breyer did not speak at all during the oral arguments in Hamer and Wisconsin Central Ltd. v. United States.

The remaining three justices who spoke during oral argument showed the greatest variation in their oral-argument speech patterns. First, Alito was often either very involved or hardly involved at all in oral arguments this term.

Alito had multiple arguments with over 1,000 words and several more with over 900 words. He spoke his most in two of the voting-rights cases this term – Gill and Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky. On the other hand, he had little to say in several hot-button cases, including the Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association (previously Christie) case, dealing with the legalization of sports betting, and the important patent case Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC.

While less active across the board and with no 1,000-word arguments, Roberts was fairly consistent in his participation at either a moderate or low level during most oral arguments.

Roberts had very little involvement in the Dimaya argument, as well as in some of the less discussed cases of the term. He was more involved in several of the term’s most salient arguments, including in Masterpiece Cakeshop and Gill.

Like Alito, Gorsuch appeared to engage deeply in certain arguments and to predominantly avoid speaking in several other arguments this term.

This juxtaposition might have been most apparent at the beginning of the term, when Gorsuch did not speak at all during the Supreme Court’s first argument of the term – Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis – and then spoke more than he did in any other argument this term in the next argument – Dimaya. Although Gorsuch hovered around 100 words or fewer in a handful of arguments this term, he was one of the most vocal contributors in several of the term’s most important cases, including Oil States and Carpenter.

That’s a wrap

The justices each treat oral argument differently, as is apparent from their behavior this term. Some of this is made clearer in the next figure, which looks at the frequency of the justices’ questions based on their words per question.

The justices at the top of the figure tend to say a lot relative to the number of questions they ask. In this respect they may be seeking different types of information than some of the other justices. Given that Kennedy and Ginsburg speak the least at oral argument, they appear to efficiently choose when to engage. Alito and Gorsuch speak the fewest words per question, indicating that they tend to frame their speaking turns around questions. These two justices are also exceptionally close in their words-to-questions ratios, which may be meaningless or may mean they have similar goals for oral argument.

With most of the cases this term still undecided and oral arguments complete, the justices have many cases to resolve based at least in part on the information provided during oral argument. In each of their unique ways, the justices used oral argument to reach certain conclusions about their positions and the positions of their colleagues. This term’s arguments helped give us a much better sense of how Gorsuch fits into the oral argument schematic as a justice who may participate little if at all in certain arguments and dominate the discussion in others. With several of the older justices’ minimal participation in oral argument, other justices — particularly Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan – have had the opportunity to fill any voids in the conversation.

An earlier version of this post indicated that oral argument in Abbott v. Perez lasted the normally allotted one hour. In fact, ten minutes were added.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Corrections, Empirical SCOTUS