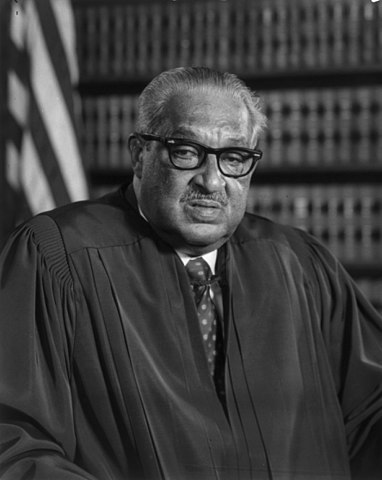

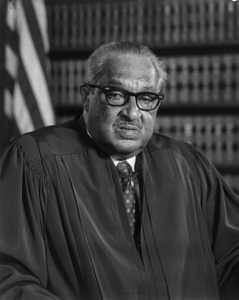

Thurgood Marshall remembered by Justice Kagan and other former clerks

“His voice is still in my head,” Justice Elena Kagan told the audience on Tuesday when asked how her former boss, Justice Thurgood Marshall, had affected her life. Kagan, along with three other former Marshall clerks, described a justice who demanded much from his clerks, but gave his time and knowledge generously in return. They also remarked on the peculiarity of working for, as one panelist put it, “not just a regular Supreme Court justice, but a living legend.”

In addition to Kagan, the event, which was hosted by the Supreme Court Historical Society, featured Harvard Law School professor Randall Kennedy, Judge Paul Engelmayer of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, and Judge Douglas Ginsburg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, who also moderated the panel.

The evening was filled with reminiscences about working for Marshall. The former clerks recalled Marshall’s fierce commitment to his values and his dogged pursuit of what he believed was right. As an example, Kagan pointed to Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public Schools, a case involving a schoolgirl in rural North Dakota whose family had to pay for her to take a bus to a school 15 miles away and who challenged the fee structure as a violation of the Constitution’s equal protection clause. Kagan told Marshall that it would be difficult for the schoolgirl to win, because the court’s prior cases suggested that the fee structure would be upheld under a lenient standard of review. Marshall rejected her analysis immediately; Kagan explained that he believed he was on the court to “make sure that people like Kadrmas got to school every day, and he was going to do what he could to make that happen.”

Kennedy told the story of Batson v. Kentucky, in which the court ruled that peremptory challenges used by prosecutors to strike jurors based solely on their race are unconstitutional. Kennedy explained that the court only agreed to hear Batson after Marshall had filed dissent after dissent from the court’s denial of certiorari in similar cases. Even after his colleagues finally agreed to hear the case and adopted his position, Marshall wrote a concurring opinion, arguing that the court wasn’t going far enough. Kennedy explained that Marshall’s willingness to constantly “push the envelope is what I admired about him.”

Engelmayer remembered City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., in which the court ruled that Richmond’s plan to ensure that a certain percentage of construction contracts were awarded to minority-owned businesses was unconstitutional. Marshall was very distressed by the outcome and instructed his clerks to point out in his dissent the irony of the former capital of the Confederacy’s attempting to do something progressive and being shut down.

Marshall’s convictions would sometimes take him to surprising places. Kagan recalled Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co., in which a group of Hispanic employees lost an employment discrimination case. Jose Torres’ name was left off the subsequent notice of appeal because of a clerical error, so he was unable to take part in the appeal. Marshall’s clerks believed that Torres should win, but Marshall ended up overruling them and writing the Supreme Court’s 8-1 decision against Torres. Kagan explained that “playing by the rules was one of the most important principles for [Marshall],” even if doing so produced undesirable results.

The panelists traced much of Marshall’s ideology to his time crisscrossing the Jim Crow south as an attorney for the NAACP. Engelmayer noted that it took a great deal of physical courage to work as a defense attorney representing black people in the south. He recalled Marshall telling stories of being moved between houses in the middle of the night for his protection and taking note of who was sleeping closest to windows in case a bomb was thrown into the room. According to the panelists, these experiences influenced Marshall’s decision to dissent in every capital case that came before the Supreme Court, because he had represented many black defendants who were executed or lynched.

Though Marshall witnessed many painful things in his career, each former clerk agreed that humor was one of the justice’s defining characteristics. During a discussion of the death penalty, Kagan remembered, Marshall declared that when one of his clients was sentenced to life in prison rather than condemned to death, “he absolutely knew that the guy was innocent.” Each former clerk described his or her first conversation with Marshall, all following a similar pattern. In Kagan’s case, Marshall called and asked, “So, you want a job?,” to which Kagan replied, “I’d love a job.” Marshall deliberately misheard her and replied, “Oh, so you have a job?” This kind of back and forth continued until Marshall warned his future clerks to prepare to write dissents, and then hung up.

During deliberations over a case, Marshall would tease and joke with his clerks. Kennedy once told Marshall that if he ruled the way he was intending, he would contradict one of his own earlier decisions. In response, Marshall asked Kennedy, “Do I have to be a damned fool all my life?” Likewise, Kagan recalled that, when told that he had to rule one way or another, Marshall often retorted: “There are only two things that I have to do: stay black and die.”

Clerking for Marshall was demanding and stressful, but the clerks were all able to step back and realize how much their boss meant to others. For Engelmayer, one such moment came when the justice took his clerks out for lunch. As their group walked into the dining room, everyone fell silent and stood up until Marshall motioned for them to sit down. Kennedy remarked on how intimidated he was when he first met Marshall face to face, in large part because he grew up hearing his father repeat a story about seeing Marshall argue a case in South Carolina challenging an all-white primary election. To Kennedy’s father, hearing Marshall referred to as “Mr. Marshall,” a title seldom given to black men in the Jim Crow south, made a lasting impression. At the end of Kennedy’s clerkship, his father was able to meet Marshall and tell him about that argument in South Carolina.

Kagan closed the evening on a lighthearted note. On the last day of her clerkship, when Kagan’s parents came to the court, Marshall was nicer than he had been all year. “That was the only time I knew that he liked me,” she said.

This post has been updated to reflect that Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public Schools originated from a dispute in North Dakota, not Kansas.

Posted in Supreme Court history, What's Happening Now