Argument preview: Interstate water dispute over Elephant Butte Reservoir and the Rio Grande Compact

Ryke Longest is a clinical professor at Duke University School of Law and Nicholas School of the Environment. He teaches water resources law and directs the Duke Environmental Law and Policy Clinic.

On January 8, the Supreme Court will hear an original jurisdiction dispute among three states that share interests in the flows of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo del Norte: Texas, Colorado and New Mexico. The congressionally approved Rio Grande Compact of 1938 apportioned water rights among these states.  In 2014, the Supreme Court granted Texas’ motion for leave to file a complaint and the court’s appointed special master, A. Gregory Grimsal, has been working through preliminary matters since then. The United States filed a complaint in intervention against New Mexico as well. The upcoming argument focuses on the first interim report by the special master, which considered a motion to dismiss filed by New Mexico against the state of Texas and the United States and motions to intervene filed by an irrigation district and a water improvement district. On October 10, 2017, the court denied New Mexico’s motion to dismiss Texas’ complaint and denied the intervention motions by the two local water entities. The exception of the United States and the first exception of Colorado to the first interim report of the special master were set for oral argument, and those matters will be before the court on Monday, January 8, as part of an interstate-apportionment double header.

In 2014, the Supreme Court granted Texas’ motion for leave to file a complaint and the court’s appointed special master, A. Gregory Grimsal, has been working through preliminary matters since then. The United States filed a complaint in intervention against New Mexico as well. The upcoming argument focuses on the first interim report by the special master, which considered a motion to dismiss filed by New Mexico against the state of Texas and the United States and motions to intervene filed by an irrigation district and a water improvement district. On October 10, 2017, the court denied New Mexico’s motion to dismiss Texas’ complaint and denied the intervention motions by the two local water entities. The exception of the United States and the first exception of Colorado to the first interim report of the special master were set for oral argument, and those matters will be before the court on Monday, January 8, as part of an interstate-apportionment double header.

The Rio Grande River in the 20th century

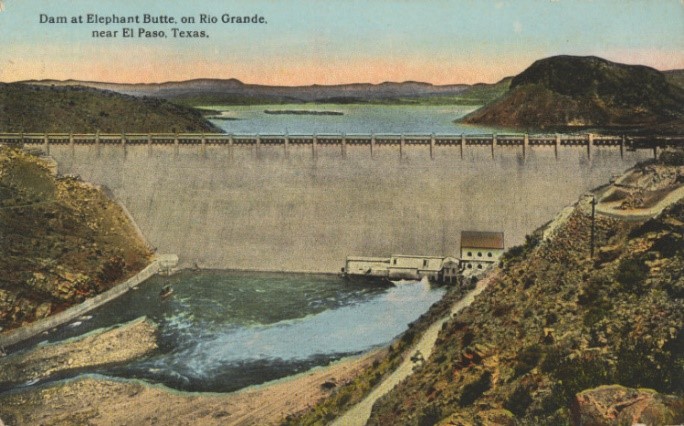

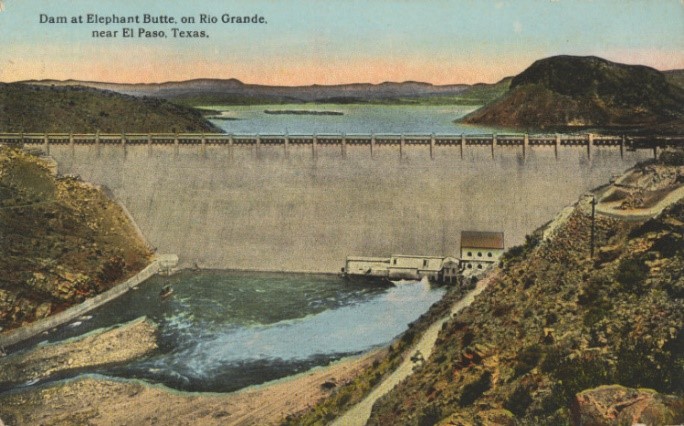

The Rio Grande forms the 1250-mile international boundary between the United States and Mexico, established primarily as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In the United States, the river begins as a stream in Colorado and winds southward approximately 400 miles across New Mexico and into Texas. In New Mexico, the river is dammed at Elephant Butte, near the city of Truth or Consequences. The Rio Grande Project, authorized by Congress in 1905, is administered by the United States Bureau of Reclamation and brings the federal government directly into aspects of the dispute between Texas and New Mexico. Texas, Colorado and New Mexico negotiated a compact that sought to resolve their disputes over water rights in the Rio Grande; the compact was ratified by Congress in 1939. The compact is administered by the Rio Grande Compact Commission, which includes representatives from each state. These representatives often disagree on questions of accounting for water allocation among the states under the compact. For example, see the Rio Grande Compact Commission Report of 2015.

Original jurisdiction complaints over compact and Rio Grande Project

Texas alleged in its complaint that New Mexico has violated the 1938 compact because officers, agents and political subdivisions of New Mexico have allowed diversions of surface water from the basin and pumping of groundwater, which is hydrologically connected to the Rio Grande downstream of Elephant Butte reservoir. New Mexico argues that the compact does not require it to prevent development downstream of Elephant Butte. New Mexico claims that the case should be dismissed because there is no allegation that it has violated its duty with respect to water delivery to Elephant Butte reservoir, saying that “[i]n sum, New Mexico’s duty under the Compact is to deliver water to Elephant Butte.” The United States opposed New Mexico’s motion to dismiss. The special master recommended that the Supreme Court deny the motion to dismiss, which it did in October.

Texas’ complaint goes beyond a mere disagreement over accounting methodology. Texas argues that New Mexico is allowing its residents to take water reserved under the compact for Texas and its residents. The compact, Texas maintains, requires delivery of a minimum amount of water to Elephant Butte reservoir and then reserves that minimum amount to traverse through New Mexico unimpeded for the use of Rio Grande Project beneficiaries located in Texas.

The United States’ complaint in intervention basically adopts Texas’ factual rationale as well as its interpretation of the 1938 compact’s duties. The United States asserted jurisdiction under both 28 U.S.C. § 1251(b)(2) and Article III, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution. The special master recommended that the Supreme Court dismiss the complaint of the United States for relief under the 1938 compact but grant an extension of jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1251(b)(2) in order to allow the intervention on claims under federal reclamation-law principles to preserve judicial economy and protect the interstate and international interests of the federal government in the Rio Grande Project.

In analyzing New Mexico’s motion, the special master observed that the United States typically appears as an amicus, not an intervening party, in original jurisdiction disputes between states over water allocation. He noted the occasional exceptional case:

On occasion, the United States has been granted leave to intervene as a party in original actions to apportion interstate streams among States; in those contexts, the United States intervenes to protect unique sovereign interests regarding federal reclamation projects or Native American relations. … The case of Nebraska v. Wyoming provides useful instruction as to the scope of the United States’ role both initially in an action to apportion the waters of an interstate stream, as well as the scope of its role in a subsequent action to enforce the decree or compact apportioning a stream.

Under the special master’s analysis, the United States’ complaint here is too broad an assertion of federal power. He wrote:

But the 1938 Compact is an agreement among three quasi-sovereign States to apportion the Rio Grande – to which each has an equitable right – among themselves. The United States is not a signatory to the 1938 Compact – indeed, it received no apportionment of Rio Grande water through the compact. The United States has no claim itself to the natural flow of an interstate stream, as does a State through which the stream passes.

Expect New Mexico to argue on Monday that the United States has no rights under the compact or federal law and that the special master erred to the extent that he decided otherwise. The solicitor general will argue that the special master erred by failing to recognize the federal interest arising under the compact, most importantly the federal government’s obligations under treaties with Mexico to deliver water.

The second case on Monday’s argument calendar is also an original jurisdiction dispute between the states over water rights — Florida v. Georgia, previewed here.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado