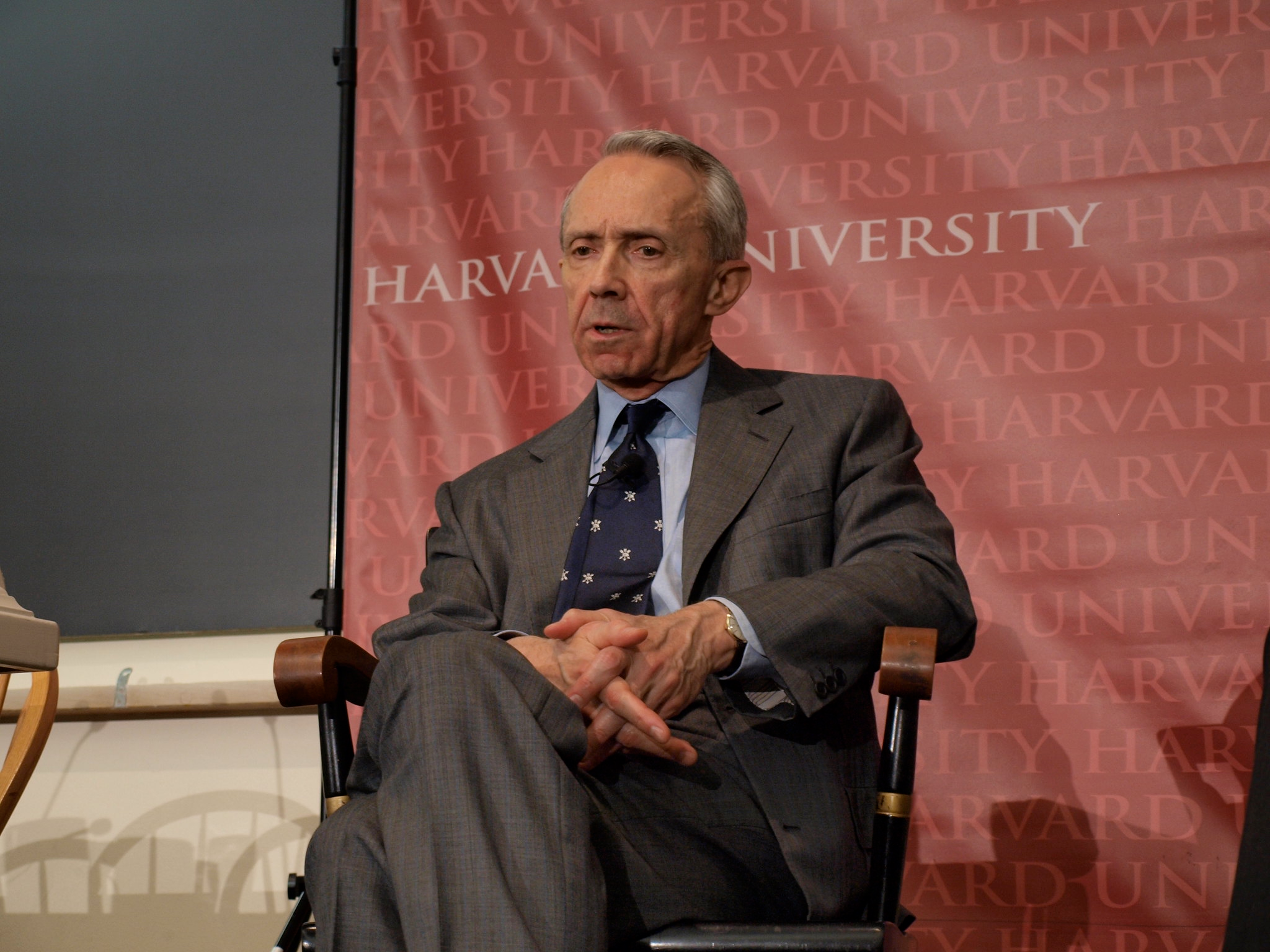

David Souter, retired Supreme Court justice, dies at 85

This article was updated on May 9 at 2:42 p.m.

Retired Justice David Souter, who was appointed to the Supreme Court by a Republican president but became a reliable member of the court’s liberal bloc during his 19 years there – so much so that the phrase “No more Souters” became a rallying cry when future Republican presidents had the opportunity to fill vacancies on the court – died on Thursday at his home in New Hampshire. He was 85 years old.

In a statement released by the court’s Public Information Office on Friday, Chief Justice John Roberts remembered Souter, saying that he “brought uncommon wisdom and kindness to a lifetime of public service.” Souter, Roberts concluded, “will be greatly missed.” Each of the current members of the court, and the two retired justices, issued statements remembering Souter on Friday afternoon.

David Hackett Souter was born on September 17, 1939, in Melrose, Mass. He graduated from Harvard College in 1961. He was named a Rhodes Scholar, spending two years at Oxford University’s Magdalen College, from which he received a master’s degree in jurisprudence in 1963.

After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1966, Souter spent two years in private practice at Orr and Reno, a small firm in Concord.

Souter then began a stint in state government, working for Warren Rudman, then the attorney general of New Hampshire. Over the next eight years, he served as an assistant attorney general and then a deputy attorney general before being appointed as the attorney general in 1976. He served in that role for two years before being named as a judge on a state trial court. In 1983, he was named to the state supreme court, where he served for seven years before he was unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate to the United States Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit on May 25, 1990.

But Souter’s initial stay on the 1st Circuit was fleeting. In July 1990, when he was just 50 years old, Republican George H.W. Bush nominated Souter to replace liberal lion Justice William Brennan. Bush called him “extraordinarily bright” and cited his reputation for being “extraordinarily fair.”

Souter notably lacked a “paper trail”: He had not written any articles or given any speeches that might shed light on his views on controversial issues like abortion. What he did have was the backing of powerful New Hampshirites within the Bush administration, such as John Sununu, a former New Hampshire governor and Bush’s chief of staff, who had named him to the state supreme court. In an interview with the New York Times, Sununu said that he ”was looking for someone who would be a strict constructionist, consistent with basic conservative attitudes, and that’s what I got.” Sununu added that he ”was able to tell the President that I was sure he would do the same thing when he encountered Federal questions.”

Rudman, then a U.S. senator, described Souter as “the single most intellectually brilliant mind I have ever met.”

Questions and concerns about the possible effects of Souter’s confirmation on the Supreme Court’s 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, establishing a constitutional right to an abortion, dominated Souter’s confirmation hearing. Molly Yard, then the president of the National Organization for Women, said, “I tremble for this country if you confirm David Souter,” warning that he would “be the fifth vote to overturn” that decision.

Souter was eventually confirmed by a vote of 90-9 and began work on the court in Oct. 1990. He joined a court with three justices appointed by President Ronald Reagan – Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and Antonin Scalia – as well as a conservative chief justice, William Rehnquist. With the arrival of Clarence Thomas, another justice appointed by Bush, in 1991, conservative hopes for a sea change at the court were high.

But less than two years later, Souter would assuage the fears of abortion-rights advocates, and garner the ire of anti-abortion forces, when he joined Kennedy and O’Connor to reaffirm the fundamental right to an abortion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

In 1994, Souter authored the majority’s decision in Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet, in which the court struck down a New York law that carved out a separate school district within the religious enclave of Kiryas Joel, where a group of ultra-Orthodox Jews live. The group’s children attend private religious schools, but the separate school district created by the law ran a public special education program for children with disabilities.

Souter concluded that the law violated the Constitution’s establishment clause, which bars the government from either establishing or promoting a particular religion. Souter explained that power “over public schools belongs to the State and cannot be delegated to a local school district defined by the State in order to grant political control to a religious group.”

Souter acknowledged that “religious people (or groups of religious people) cannot be denied the opportunity to exercise the rights of citizens simply because of their religious affiliations or commitments, for such a disability would violate the right to religious free exercise.” But that does not mean, he continued, that a state can “deliberately delegate discretionary power to an individual, institution, or community on the ground of religious identity.”

More than two decades later, Souter once again wrote an opinion for the court that drew a line between church and state. In McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union, the justices – by a vote of 5-4 – ruled that two Kentucky counties could not display large copies of the Ten Commandments in their courthouses. The displays violated the establishment clause, Souter concluded (in an opinion joined by O’Connor and Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer).

Souter explained that a government entity’s purpose in taking an action like displaying the Ten Commandments “needs to be taken seriously under the Establishment Clause and needs to be understood in light of context; an implausible claim that the governmental purpose has changed should not carry the day in a court of law any more than in a head with common sense.”

And in Bush v. Gore, Souter joined Stevens, Ginsburg, and Breyer in dissenting from the majority’s decision to stop the recount of ballots in Florida, ordered by the Florida Supreme Court, that ultimately ensured George W. Bush the presidency.

Souter questioned the majority’s decision to intervene, arguing that if the court had not stopped the recount a few days earlier, “it is entirely possible that there would ultimately have been no issue requiring our review, and political tension could have worked itself out in the Congress.” “There is no justification,” Souter concluded, “for denying the State the opportunity to try to count all disputed ballots now.”

In his book The Nine, published in 2007, journalist Jeffrey Toobin described Souter as “shattered” by the court’s decision in Bush v. Gore – to the point that he “seriously considered resigning” from the court. “At the urging of a handful of close friends,” Toobin reported, “he decided to stay on, but his attitude toward the Court was never the same.”

After 19 years on the bench, Souter did step down in 2009, at the relatively young (for a Supreme Court justice) age of 69. Only three justices on the court at the time (Roberts, Thomas, and Justice Samuel Alito) were younger than he was. Souter’s retirement was not entirely a surprise however, as he was long believed to have disliked Washington, D.C.: He had said once that he had “the world’s best job in the world’s worst city.”

After he had announced his intent to retire but before he officially left the bench, Souter penned a dissent in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, a lawsuit brought by a conservative nonprofit prohibited from showing a movie that criticized then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in the run-up to the 2008 elections. Souter’s draft was sharply critical of the majority opinion, which would have gone well beyond what the challengers requested to instead invalidate two major campaign-finance decisions. Writing in the New Yorker, Jeffrey Toobin described Souter’s draft dissent as an “extraordinary, bridge-burning farewell to the Court” that Chief Justice John Roberts feared “could damage the Court’s credibility.” Instead of deciding the case then, Toobin reported, the court heard oral argument in the case again the following term, instructing both sides to the dispute to brief the broader questions.

After his retirement from the Supreme Court, Souter became a regular fixture back on the 1st Circuit, hearing hundreds of cases. In one of those cases, Carson v. Makin, Souter joined his colleagues in unanimously rejecting a challenge to a Maine program that paid tuition for some students to attend private schools, but barred the use of state funds for tuition at private schools that provide religious instruction.

In June 2022, the Supreme Court reversed the 1st Circuit’s ruling. Writing for a six-justice majority, Chief Justice John Roberts made clear that when state and local governments opt to subsidize private schools, they must allow families to use those subsidies to pay for religious schools. Any other result, Roberts explained, would be “discrimination against religion.”

The court’s ruling in Carson was the third of three decisions opening the door for the use of public funding for religious schools. The justices heard oral arguments last week in a case seeking to extend that trio of decisions to allow the establishment of the country’s first religious charter school. A decision in that case is expected by late June or early July.

[Disclosure: I was among the lawyers on the legal team at the Supreme Court for then-Vice President Al Gore in Bush v. Gore.]

Posted in In Memoriam