A fast-moving argument over medication abortion

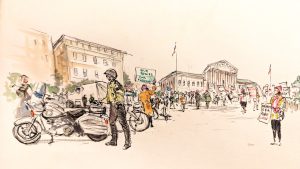

It’s a crisp morning here as Washington’s famous cherry blossoms are holding on to their leaves and color a good eight days after they reached an unexpectedly early peak bloom. The court has some of the trees right on its grounds, and they will be a backdrop to much expressive activity over today’s lone case — Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, about the agency’s 2016 and 2021 actions easing access to the abortion drug mifepristone.

Without getting into specifics, security is tighter than normal both outside and inside the courtroom as the justices take up their first case on abortion access since they overturned the constitutional right in 2022.

Inside the nearly full courtroom (only the bar section has a few empty seats), I scan the public gallery looking for one particular former Supreme Court law clerk. Soon enough, I see Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., seated in the front row on the south side. He is married to Erin Hawley, who will argue for the challengers this morning. Both clerked for Chief Justice John Roberts during the court’s 2007-08 term.

I am a bit taken aback to see another familiar face a few seats away. New York Attorney General Letitia James is also in the same front row of the public section. While universes seem to be colliding, James did file a “friend of the court” brief for New York and 22 other states (plus the District of Columbia) in this case, supporting the FDA. And James will have something to say later to the crowd of abortion-rights supporters outside the court.

In the bar section, Kristen Waggoner, the president and general counsel of Alliance Defending Freedom, the organization representing the anti-abortion doctors and medical associations that challenged FDA’s actions on mifepristone. Waggoner, who has argued several cases here, will approach the lectern to move the admission of a new bar member, but will leave the arguments to Hawley.

Unlike Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and the dual arguments in 2021 over who could challenge the restrictive Texas S.B. 8 abortion law, which included arguments by one and three men, today’s arguments will all be carried out by women. (This is unusual at the Supreme Court, where in recent years women argued less than a quarter of the cases before the justices.)

The arguments today centered mostly on whether any of the doctors who are plaintiffs have a legal right to sue, known as standing, based on their theory that they might face treating a woman who used mifepristone and ended up in an emergency room with complications that would require a doctor with a conscience objection to abortion to participate in such a procedure. U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar said this is too tenuous a connection, and they therefore did not have standing.

The challengers’ “theories rest on a long chain of remote contingencies,” the solicitor general says. “Only an exceptionally small number of women suffer the kind of serious complications that could trigger any need for emergency treatment. It’s speculative that any of those women would seek care from the two specific doctors who asserted conscience injuries. And even if that happened, federal conscience protections would guard against the injury the doctors face.”

When it’s her turn, Hawley argues that the challengers have standing “because, one, the FDA relies on [obstetrician] hospitalists to care for women harmed by abortion drugs. Two, the FDA concedes between 2.9 and 4.6 percent of women will end up in the emergency room and, three, the FDA acknowledges that women are even more likely to need surgical intervention and other medical care without an in-person visit.”

There is frequent discussion of two individual challengers who Hawley contends have objections of conscience to participating in any abortion procedures. Those doctors, Christina Francis and Ingrid Skop, are in the courtroom today.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett pushes Hawley on those doctors’ official statements, saying, “I think the difficulty here is that at least to me, these affidavits do read more like the conscience objection is strictly to actually participating in the abortion to end the life of the embryo or fetus. And I don’t read either Skop or Francis to say that they ever participated in that.”

Some of the other justices were more than happy to move on to the merits. Justice Samuel Alito, the author of the Dobbs decision overruling Roe v. Wade, asks about an issue that was part of the plaintiffs’ lawsuit at the district court but set aside by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit and only sparsely addressed in the merits briefs before the high court. “Shouldn’t the FDA have at least considered the application of 18 U.S.C. 1461?” he asks Prelogar, somewhat coyly avoiding the better-known identifier for the 19th century federal law that bars using the mail to deliver any drug meant to be used for “producing abortion.”

Prelogar is quick to refer to that better-known name, the Comstock Act, which was later amended to also apply to delivery of abortion drugs by “common carrier” or “Interactive mail service.”

Justice Clarence Thomas returns to the Comstock Act in his questioning of Jessica Ellsworth, representing the drug manufacturer, Danco.

“My problem is that you’re private,” Thomas tells Ellsworth in reference to Danco. “The statute doesn’t have this sort of safe harbor that you’re suggesting. And it’s fairly broad, and it specifically covers drugs such as yours.”

Hawley jumps at Thomas’s request for her to comment on the application of the Comstock Act.

“We don’t think that there’s any case of this court that empowers FDA to ignore other federal law,” Hawley says. “As relevant here, the Comstock Act says that drugs should not be mailed … So we think that the plain text of that, Your Honor, is pretty clear.”

Meanwhile, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson is willing to counter Alito’s aggressive line of questioning of Ellsworth, regarding whether the FDA had ever approved a drug and later had to pull it because of serious adverse consequences. (“It has certainly done that,” she replied.)

“I just have one quick question,” Jackson says to Ellsworth. “So you were asked if the agency is infallible and I guess I’m wondering about the flip side, which is, do you think that courts have specialized scientific knowledge with respect to pharmaceuticals and as a company

that has pharmaceuticals, do you have concerns about judges parsing medical and scientific studies?”

Yes, Ellsworth says, pointing to “friend of the court” briefs from the pharmaceutical industry and adding that “FDA has many hundreds of pages of analysis in the record of what the scientific data showed. And courts are just not in a position to parse through and second-guess that.”

As the fast-moving 93-minute argument draws to a close, Sen. Hawley slips out of the courtroom just as Prelogar is starting her short rebuttal.

Outside the court building, I bump into James and say hello. There are so many questions I could think of to ask her about various pending legal matters. But she is walking briskly to the front of the building to address abortion access supporters (where she will be introduced over a loudspeaker as a “legal badass.”)

Some of the doctors who are among the challengers don their medical coats to join Hawley, Waggoner, and others from Alliance Defending Freedom before a bank of press cameras and microphones. (Ellsworth and a colleague will also address the press scrum a few minutes later on behalf of Danco.)

But their words are mostly drowned out by the two opposing groups, numbering in the hundreds, who are carrying on loudly with their separate rallies on the sidewalk.

The midday sun has warmed up the air and made the nearby cherry blossoms appear even more brilliant.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, Danco Laboratories, L.L.C. v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine