Symposium: Liquidating elector discretion

Rebecca Green is professor of the practice of law and co-director of the Election Law Program at William & Mary Law School.

In a 2014 case called National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning, the Supreme Court blessed a method of interpretation known as “liquidation” that seeks to identify settled practice as a means of understanding ambiguous constitutional text. Since then, scholars like law professor Will Baude have elaborated on James Madison’s idea that resolving constitutional vagaries can be achieved through identifying “a regular course of practice to liquidate and settle [its] meaning.”

The petitioners in Colorado Department of State v. Baca picked up on this thread, citing Noel Canning to argue that “well-established post-enactment understanding by the public [that electors perform a mere ministerial role], coupled with longstanding historical practice,” should be understood to establish that states may constitutionally penalize or remove defecting electors.

In a recent law review article, “Liquidating Elector Discretion,” I challenge this narrative, marshalling evidence that the opposite is true: that settled practice in fact assumes elector discretion.

What does a liquidation analysis entail? Drawing on Madison’s writings, Baude identifies three elements: (1) the presence of a discrete textual indeterminacy; (2) a course of deliberate practice; and (3) actual settlement of the ambiguity revealed by institutional and public acquiescence to the practice in question. What might this analysis reveal in resolving the constitutionality of electors’ exercising discretion? Let’s take each in turn.

Textual indeterminacy

Textual ambiguity is clearly present. The 12th Amendment directs electors to “vote” by “ballot,” but does not settle whether electors must be permitted to exercise discretion when casting their ballots. Federal statutes add little meat to the bones on this question.

Aspects of this design have been litigated. For example, the Supreme Court held in Ray v. Blair that political parties may require electors to take pledges to vote for a particular candidate.

But the Supreme Court has not resolved the question of whether states may punish or remove electors who violate that pledge. The split between the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in Baca and the Washington Supreme Court in Chiafalo v. Washington arises from this textual indeterminacy.

Course of deliberate practice

On the second question, whether a course of deliberate practice establishes elector discretion, four factors point to discretion as the default: frequency, geography, ballot design and accountability.

Frequency. Electors have defected throughout U.S. history. According to FairVote, 165 electors have cast their vote for someone other than the candidate with the most votes in their state (90 for president and 75 for vice president). Of those electors, 71 defected because the candidate chosen by popular vote in their state died before the Electoral College met (63 for president and 8 for vice president). Dozens of electors thus exercised discretion to vote for someone other than the popular-vote winner in their state. If, in the course of deliberate practice, electors played only a ministerial role, why the steady trickle of defectors throughout the decades? It is not the case that electors used to defect and now do not. 10 of the 18 most recent elections featured at least one defecting elector.

One might counter that the vast majority of Electoral College votes have tracked the majority vote winner in their state—only .67 percent of electors have voted for candidates other than the one they pledged to elect. But that something happens rarely does not mean that its occurrence is not settled. By design, elector defection is meant to happen infrequently. Electors will choose to follow popular will in their states unless extraordinary circumstances demand. Electors sacrifice their political life and reputation to cast a faithless vote for the perceived good of the nation. That defection happens rarely is an intended feature of Electoral College design.

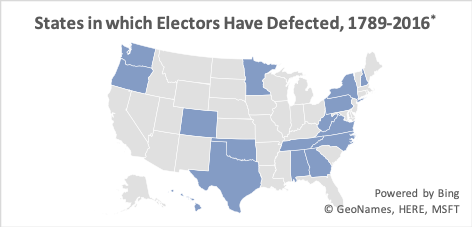

Geography. Defections have not clustered in one geographic region. Elector defections—even excluding those resulting from the death of a candidate—have been dispersed geographically, as the map below illustrates:

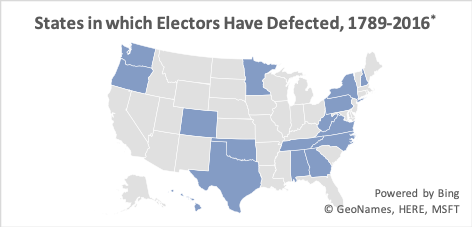

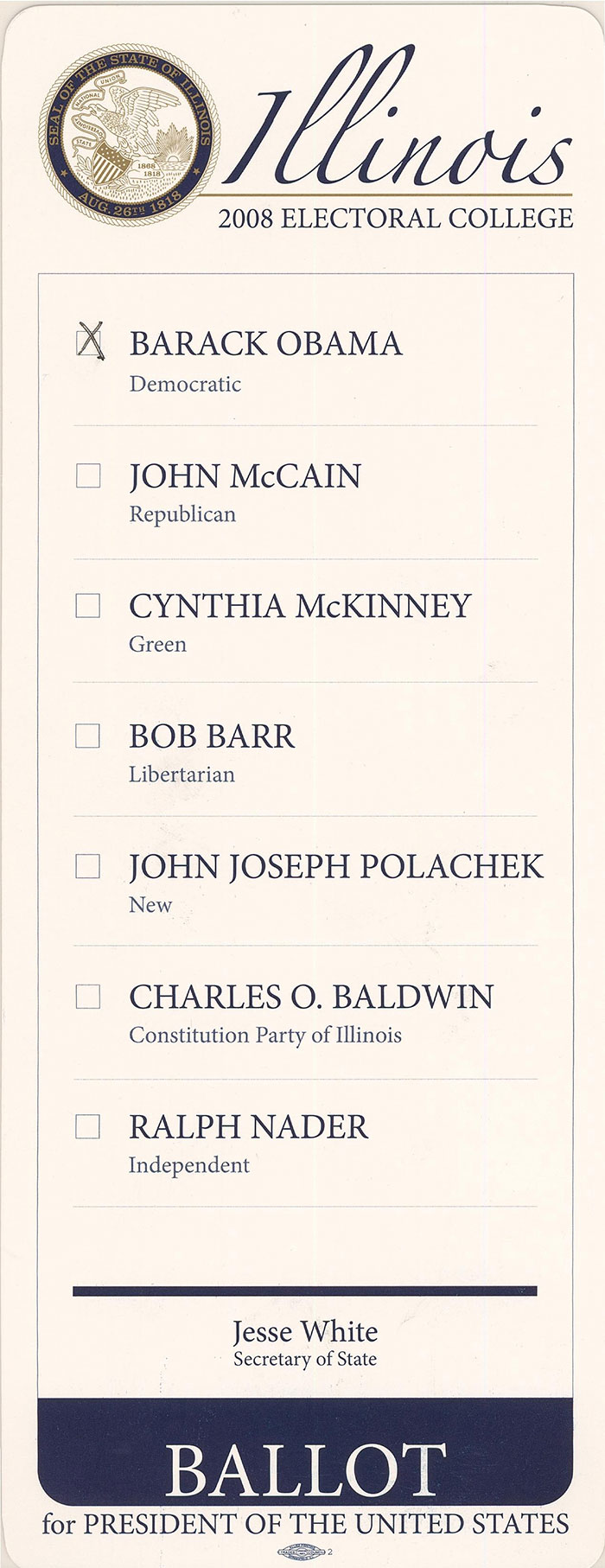

Ballot design. If electors acted in a ministerial role only, how can we explain states’ routinely handing electors ballots that clearly anticipate discretion? Here are two examples of many, from Illinois (2008) and Texas (2016):

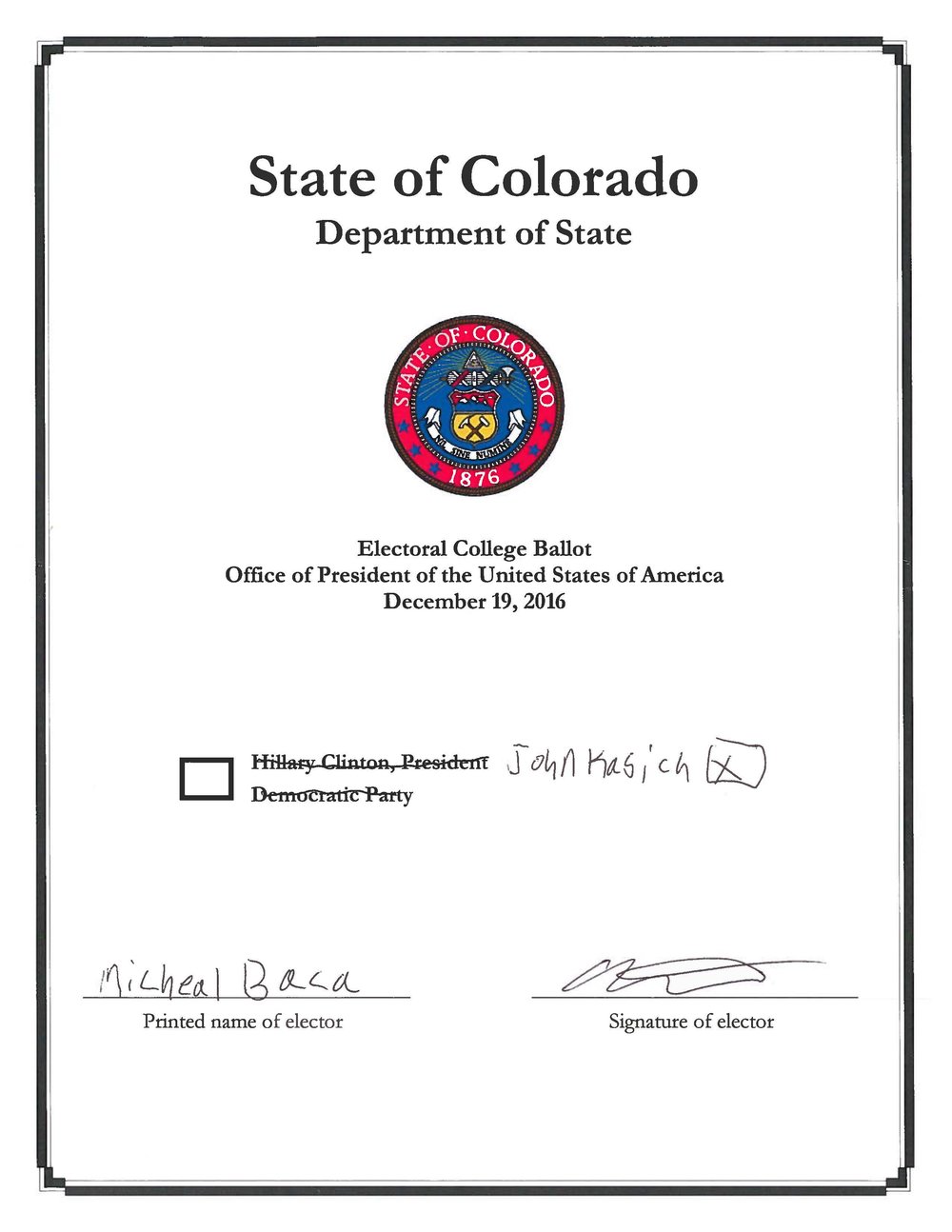

Even when elector ballots do not as clearly anticipate choice, it is hard to hand an elector a ballot and a pen and expect otherwise, as Micheal Baca himself demonstrated:

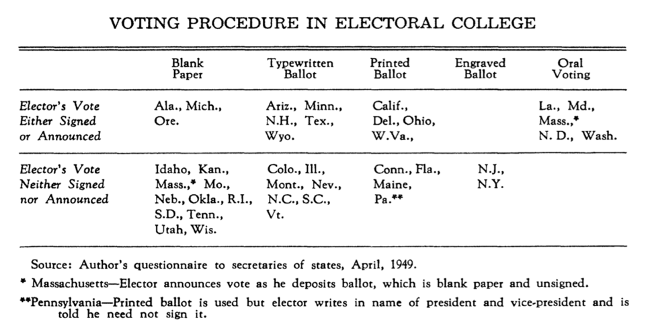

Accountability. One might expect, were it a deliberate course of practice to deny electors discretion, that states would universally hold electors accountable for cast votes. But evidence suggests that states have not always done so. In 2004, for example, an elector defected in Minnesota, but no one knew who it was because balloting had been conducted in secret. It appears that no comprehensive study has been undertaken to determine the extent to which electors have historically been held accountable for their vote. One historian, writing in 1949, collected evidence suggesting that quite a few states did not require electors to sign their ballot or otherwise be held to account (see row of states in which the “Elector’s Vote [is] Neither Signed nor Announced”):

Faithless electors have appeared throughout U.S. history (albeit rarely), instances have been geographically dispersed, states routinely hand electors ballots anticipating choice and states do not uniformly require elector accountability. These realities undermine claims that a “deliberate course of practice” relegates electors to an exclusively ministerial role.

Institutional and public acquiescence

The third prong of Baude’s framework requires examining “settlement,” or the degree of institutional and popular acquiescence.

Institutional acquiescence. At the federal level, Congress has yet to turn away a faithless elector’s vote. Undeniably the picture at the state level is muddled. But at least as of the 2008 presidential election, it appears that no state had punished a defecting elector. Why? One source suggested that states had not punished faithless electors because “experts doubt[ed] that it would be constitutionally possible to do so.”

Popular acceptance. Widespread public calls for electors to vote their conscience in 2016 demonstrate that the public assumed that electors would have discretion when extraordinary conditions arose. The 2016 election presented an atypical trifecta: The winner of the popular vote failed to capture the White House, troubling evidence of foreign interference in the election swirled and many believed the presumptive Electoral College winner was unfit for office.

These unprecedented circumstances unleashed a torrent of popular pressure on electors to defect. Americans lobbied electors through letter campaigns and newspaper opinion columns. A “Conscientious Elector” petition at Change.org gained millions of signatures imploring electors to cast their vote for the popular vote winner. Electors felt the heat. A USA Today headline blared: “Harassment or Hail Mary? Electors feel besieged.” A Politico story titled “Electors under siege” recounted how “once-anonymous electors are squarely in the spotlight, targeted by death threats, harassing phone calls and reams of hate mail,” noting that “[o]ne Texas Republican elector said he’s been bombarded with more than 200,000 emails.” Some states hired protection for besieged electors.

Massive popular pressure on electors to change their votes in 2016 demonstrates that the American public fervently believed electors have discretion.

* * *

There are lots of reasons to doubt whether liquidation can resolve the constitutionality of states’ binding electors. Liquidating the actions of federal bodies is much more straightforward than attempting to nail down settled practice in 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Also, importantly, as Baude describes, looking to settled practice is a form of constitutional interpretation intended to minimize disruption. If the Supreme Court hands electors the power to vote their conscience in November 2020 and they in fact upset the result, massive protests would certainly erupt. The least disruptive path forward would be to allow states to bind electors.

Where does this leave us? The petitioners in Baca assert that settled practice argues against elector discretion. The above discussion provides fodder for the idea that Electoral College norms and practice routinely anticipate elector discretion, and that institutions and the populace generally accept it. But the argument that settled practice invariably points to elector discretion is far from a slam dunk. Perhaps the safest ground is to conclude that liquidation proves neither side adequately, despite the Colorado Department of State’s assertion that it does.

Posted in Symposium before oral argument in Chiafalo v. Washington and Colorado Department of State v. Baca

Cases: Chiafalo v. Washington, Colorado Department of State v. Baca