Courtroom access: The nuts and bolts of courtroom seating – and the lines for public access

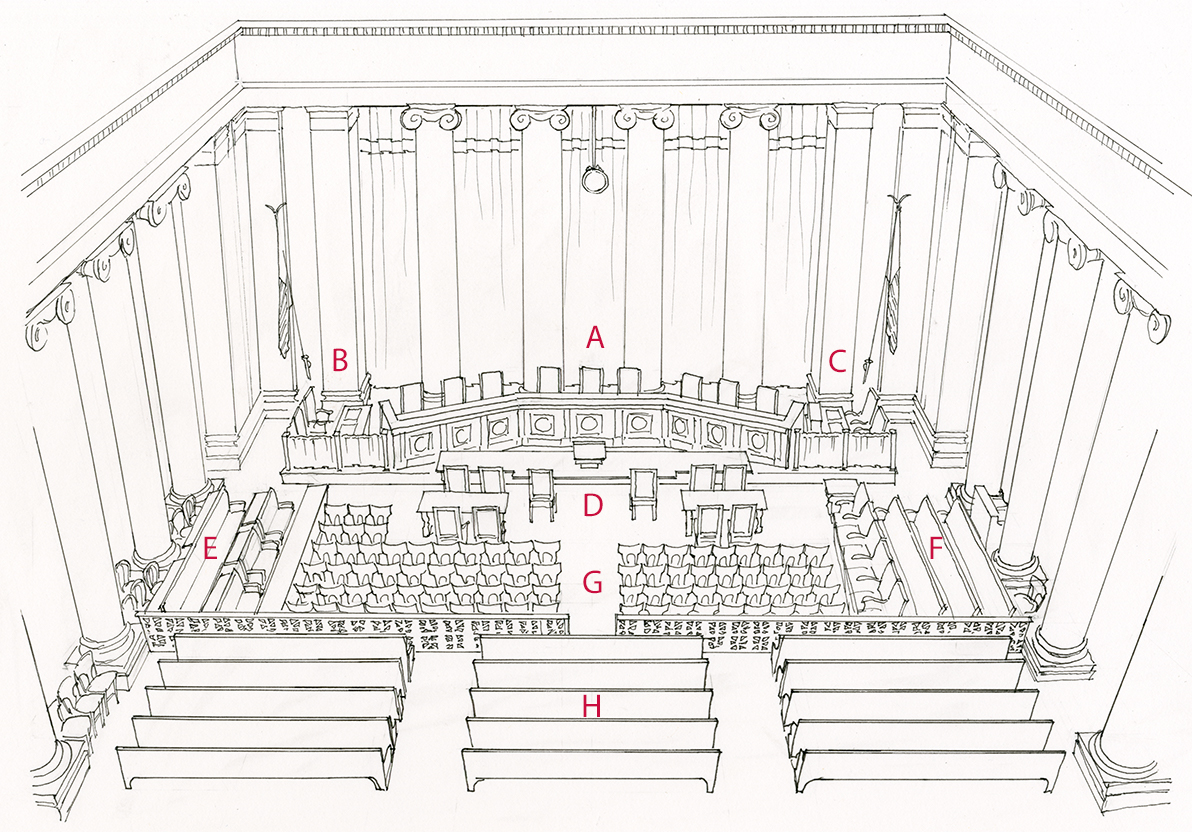

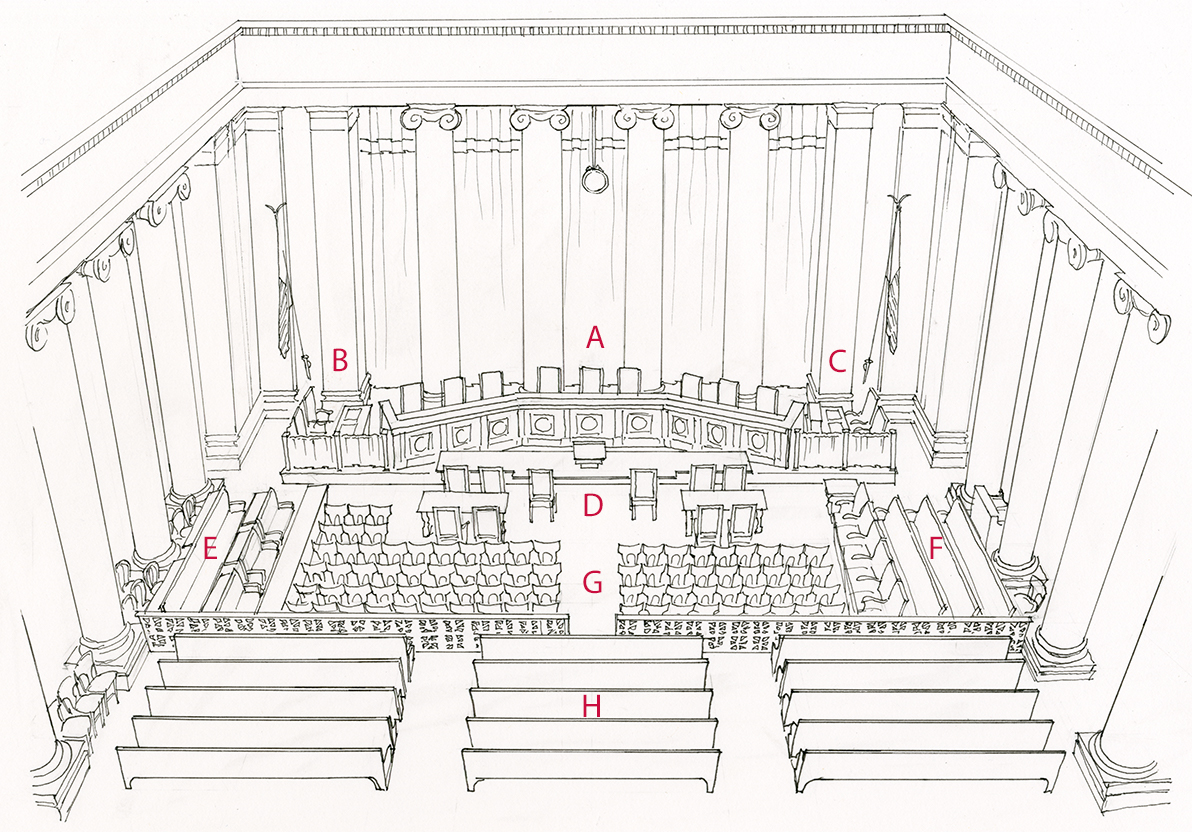

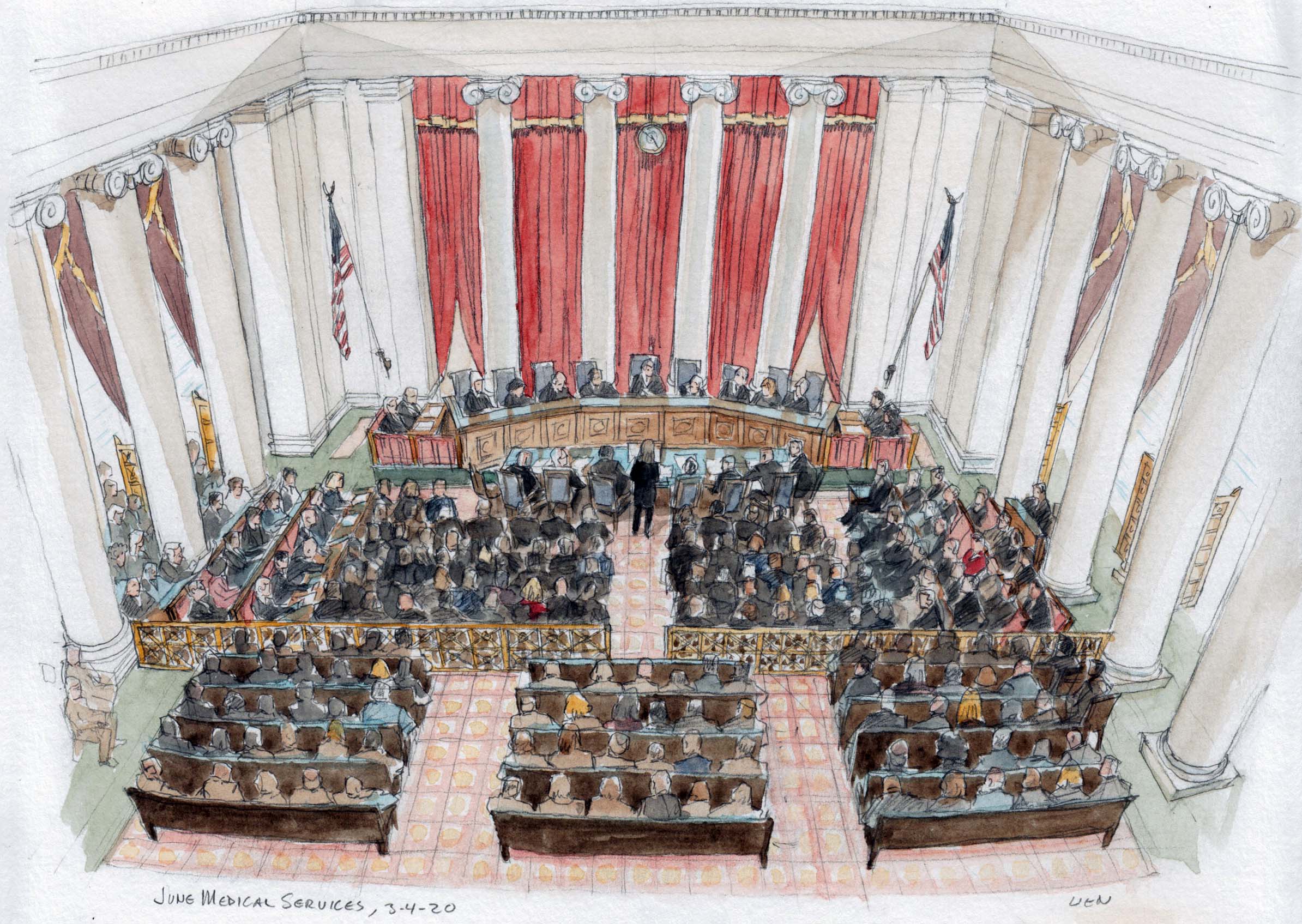

On an average argument day at the Supreme Court, there are 439 seats in the courtroom. Of those 439, only 50 – that is, just over 11 percent – are specifically set aside for members of the general public. The other 389 are divided among several different groups.

The “public line”

The line to obtain one of the 50 public seats (the so-called “public line”) forms on the sidewalk in front of the court – on the right-hand side if you are facing the Supreme Court building, with the Capitol behind you across First Street. At around 7:30 on the morning of an argument, Supreme Court police officers begin to hand out at least 50, but sometimes more, tickets. The lucky ticket-holders are then ushered into the Supreme Court building, where they can warm up, use the bathroom and store their belongings before forming a new line to enter the courtroom itself. The rest of the line stays outside, where those who didn’t make the first cut wait and hope that (as is usually but not always the case) more tickets will be distributed, normally between 9:30 and 10 a.m. Depending on whether any seats remain open, the officers may also continue to admit members of the public after arguments begin at 10 a.m.

The press corps, the justices’ box and the clerks’ seats

On one side of the courtroom, perpendicular to the bench, 36 seats are allocated to members of the press. Across the courtroom on the other side, and also perpendicular to the bench, 37 seats are reserved for retired justices, the justices’ spouses and VIP guests (including Ivanka Trump and her daughter at one argument in 2017) and senior court officials. The justices’ law clerks have 27 seats in less desirable real estate farther back in the courtroom, on the same side as the justices’ box.

The “bar section” and the “bar line”

Between the press section and the justices’ box sits the “bar section”: 78 seats reserved for members of the Supreme Court bar. Although the Supreme Court bar is sometimes described as an elite fraternity, the requirements for membership are fairly simple: To be admitted, you must have stayed out of trouble while practicing law for at least three years, find two lawyers who have already been admitted to the bar to vouch for you, and pay a $200 fee. Once admitted, you can sign briefs and argue in the Supreme Court, but one of the best perks for most people is the seating. Although there are a lot of lawyers in Washington, it’s almost always still easier to get a seat in the bar section than in the public section.

The location of the line for seats in the bar section depends on how popular the arguments are on a particular day. When the justices are hearing argument in lower-profile cases, the “bar line” may form inside the building after it opens. Lawyers line up behind a desk on the ground floor, along a wall displaying exhibits on the history of the court. But on bigger argument days, the line is likely to form outside the court, sometimes in the wee hours of the morning, and move inside (like the first wave of the public line) sometime around 7:30 a.m. No line-standers are permitted in the bar line, unlike the public line. Inside, court officials begin to hand out tickets, checking on a computer to confirm that each person in line is indeed a member of the Supreme Court bar.

Although there are 78 seats in the bar section, that doesn’t mean that the first 78 lawyers in the bar line will be guaranteed seats there. On days when the justices take the bench to hear oral arguments (as well as most non-argument sessions), they also admit new lawyers to the Supreme Court bar. Those lawyers are seated in the bar section without having to wait in line, as are the bar members who are moving their admission. On days when a lot of lawyers are being admitted, over half of the seats in the bar section may be taken before any of the tickets are handed out to regular bar members. But even if they don’t make it into the courtroom, bar members have a consolation prize that is not available to people waiting in the public line: They can sit and listen to the arguments in the lawyers’ lounge, a large room on the same floor as the courtroom where live audio is piped in over speakers.

The “three-minute line”

There are 25 seats set aside in the back of the courtroom for members of the public who wait in the “three-minute line,” which allows many people to cycle through the courtroom for three to five minutes at a time. So at some point, people waiting in the public line who don’t get one of the first wave of tickets may have to make a difficult choice. Do they continue to wait in line in the hope that they will eventually be admitted to hear the entire argument, or at least a substantial portion of it? Or do they cut their losses and move into the three-minute line, which will significantly increase their chances of getting into the courtroom – but only for long enough to hear a snippet of the proceedings?

“Reserved” seats in the public section

If you have been tallying up the seats as you read along, you know that there are still 186 seats unaccounted for. These are what are known as the “reserved” seats in the public section of the courtroom, which are overseen by the Marshal’s Office at the Supreme Court. The reserved seats are set aside for school groups, the guests of the newly admitted bar members (who get one seat each), the guests of the lawyers arguing that day (who get six seats each, unless the argument is divided, in which case they get four) and “guests of the court.” If any of these 186 seats are not being used for one of these categories, they are made available for the public line.

Our thanks to the Supreme Court Public Information Office for providing numbers and information for this post.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Courtroom Access