Argument analysis: Justices have strong views about removal of class actions

Yesterday mornings argument in Home Depot U.S.A. v. Jackson was a notable one, as Justice Elena Kagan brought a strong view of the case to the bench and proceeded to dominate the argument.

The case involves the removal of litigation from state court to federal court. Under Section 1441 (and predecessor provisions dating back to the 18th century), the defendant or the defendants generally has a right to remove any civil action brought in a State court of which the [federal] district courts have original jurisdiction. In 2005, responding to concerns that state courts have been unduly receptive to class actions, Congress adopted the Class Action Fairness Act (often called the CAFA), which included a variety of provisions designed to make it easier for class-action defendants to remove those cases to federal court. One provision, in Section 1332, granted original federal jurisdiction over most class actions seeking a recovery of more than $5 million. Another provision, in Section 1453, provided that any defendant can remove a class action as defined in Section 1332.

Together, those provisions make it clear that if a plaintiff initiates a large class action in state court, any of the defendants can remove the case to federal court. Home Depot presents an odd twist on that framework. In this case, the initial litigation was between Citibank and respondent George Jackson: Citibank sued Jackson in state court to collect a debt arising out of a purchase Jackson made that was connected to Home Depot. All agree that the Citibank action could not have been brought in (or removed to) federal court. The next step, though, is what makes the case interesting: Jackson responded by asserting both defensive claims against Citibank and a class action against Home Depot, alleging a variety of consumer-protection claims. Citibank then withdrew its claim against Jackson, leaving Home Depot alone in the litigation against Jackson. Home Depot responded by filing a petition seeking to remove the matter to federal court under the CAFA. The lower courts rejected Home Depots petition and concluded the case should return to state court.

As I explained in my preview, the parties for the most part briefed the case on the question whether Home Depot qualifies as a defendant under Section 1441 and 1453, with Home Depot arguing that as a literal matter it plainly is a defendant and Jackson arguing that the history of Section 1441 shows that the term defendant refers only to the party against whom an action initially is filed.

Kagan came to the bench with a somewhat different take on the matter, appearing strongly predisposed to rule against Home Depot because the initial complaint in this case (filed by Citibank) did not institute a civil action over which federal courts would have original jurisdiction. For her, the key to the case isnt whether Home Depot is or is not a defendant, it is whether the civil action at issue here could have been brought in federal court and it plainly could not have been. That view squarely collided with the presentation on behalf of Home Depot, represented by William Barnette.

Early on Kagan pointed out that Section 1441(a), which is the principal removal statute, says that a civil action, not claims, but a civil action can be removed where the district courts have original jurisdiction. And what Ive always taken that to mean is that to look for original jurisdiction, you look to the plaintiffs complaint, the original plaintiff. She could agree with Barnette that:

[Y]our claim might be under the original jurisdiction of the district courts if that had started the lawsuit. But that didnt start the lawsuit. The lawsuit, the civil action, was started by a claim thats completely non-federal in nature. And you look to the original claim to decide whether the courts have original jurisdiction, dont you?

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer saw the case much the same way. Sotomayor, for example, asked Barnette whether his case would fall apart if we dont accept your claim-by-claim analysis? You approach this claim by claim. Im not quite sure how we can do that since the statute speaks about a civil action and it talks about removal of an action, not a removal of a claim.

Breyer emphasized Section 1332, which says the term class action means any civil action filed under Rule 23 [or analogous state law]. Did [Jackson], the one who sued you, did he file a civil action? When Barnette suggested that Jackson had filed such an action, Breyer disagreed forcefully: I dont think he did, did he? Where does it say he did? . What he did was he filed a . [counter]claim.

Barnette continued to press his point that Home Depot should be regarded as a defendant, but Breyer kept taking the discussion back to the filing of the complaint against Home Depot by the defendant on the original complaint: Where does it say that when a defendant files a class action, that is an action filed, a civil action, because civil actions are usually filed by plaintiffs. Indeed, when Barnette persistently redirected the discussion back to his baseline position, Breyer seemed to lose patience, commenting that he was only asking a simple question and asking: Why are you still not giving direct answers?

By the end of the discussion, Breyer seemed as settled in his view as Kagan, explaining at one point: Now Im over with Justice Kagan. A civil action is an action brought by a plaintiff. And, therefore, since this isnt a civil action filed under Rule 23 [or analogous state law], they cant take advantage of 1453 because they dont fit within the definition.

Kagan summarized the discussion near the end of Barnettes presentation, explaining:

Mr. Barnette, under your theory, every time one party joins another party, we would have a new civil action. But we dont. We only have one civil action, and the civil action includes a multitude of claims, or can, between and among a wide range of parties. But its only one civil action.

[Y]oure suggesting that we should look at this case as though the original claim never occurred and we should pretend that the claim started with the original defendant. But the case did not start with the original defendant. The civil action started with the original plaintiff, who brought a claim against a defendant who then brought a claim against you.

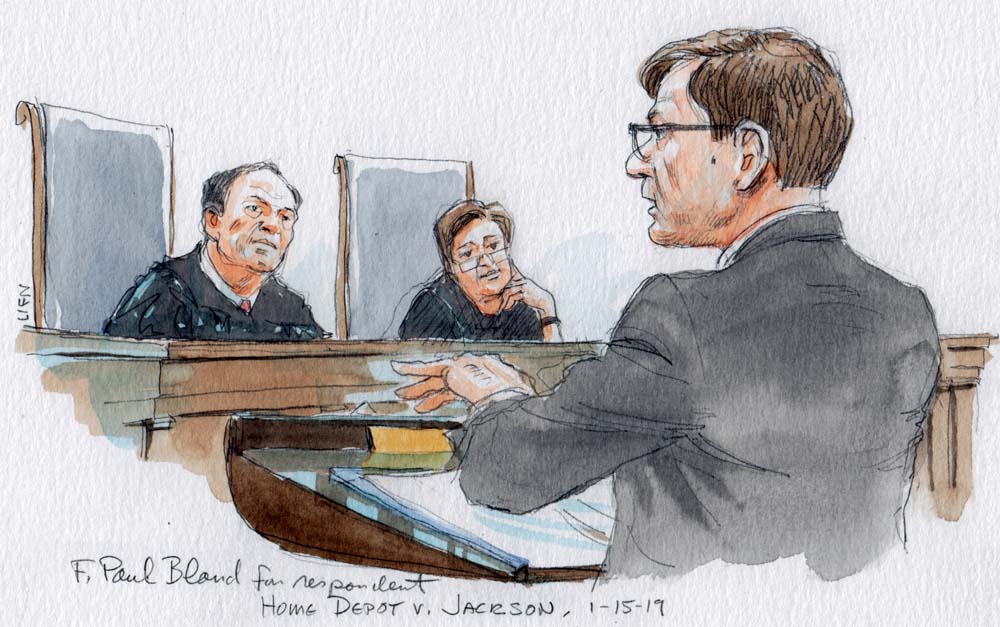

That is not to say that Paul Blands argument on behalf of Jackson was entirely stress-free. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito probed closely on the textual support for and policy implications of Blands position. When Alito started to press Bland closely, Kagan repeatedly interrupted to explain how she would analyze the problem. At one point, she engaged Alito so directly that he asked Bland whether he agree[d] with Justice Kagans answer to my question.

Bland was reluctant to embrace the position that Kagan had articulated that it is irrelevant whether Home Depot was or was not a defendant because Jackson had not filed a civil action against Home Depot. Bland spent much of his argument trying to resist comments by Alito and Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggesting that Home Depot must be accepted as a defendant. Alito, for example, commented at one point that if we look at the text, we have a reference to the defendant or the defendants. So Home Depot would qualify there, would it not? When Bland suggested that the traditional understanding of Section 1441 meant that Home Depot was not a defendant, Alito was wholly unpersuaded: Youre reading things into it. [I]n the ordinary sense of the term, are they not defendants? . They are some kind of defendants.

Alito also seemed to think affirming the decision in this case would fly in the face of Congress intent in adopting the CAFA, as he asked Bland rhetorically:

[I]s there any good reason why a claim like this should not be removable to federal court? If a claim like this is filed originally in state court, it can be removed, but if it comes into the state court in this strange sort of back-door way, then it has to stay in state court. You really think that thats a possible decision Congress would make?

At the end of the day, it is not at all clear from the argument how the court will resolve this one. We should find out by the end of June.

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is counsel to the petitioner in this case. The author of this post is not affiliated with the firm.]

Editors Note: Analysis based on transcript of oral argument.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Home Depot U.S.A. Inc. v. Jackson