Opinion analysis

Unusual alliance of justices holds government to strict notice requirement in removal proceedings

on May 2, 2021 at 3:58 pm

On Thursday, the Supreme Court issued a 6-3 decision in Niz-Chavez v. Garland, opting for a strict reading of an immigration statute that turns on whether the government has provided proper notice to a noncitizen to appear for removal proceedings. By holding the government to the plain language of the statute, and by refusing to accommodate immigration agencies’ desire for flexibility, the majority handed a win to noncitizens and their advocates, who have long criticized the government’s piecemeal approach to providing notice of removal hearings.

The timing of this notice to appear (formalized as Form I-862 Notice to Appear or “NTA”) carries significance for cancellation of removal, which is an important form of relief for noncitizens in removal proceedings. There are two kinds of cancellation of removal, and each includes a durational presence requirement – either seven years of continuous residence or 10 years of continuous physical presence. Importantly, via a provision known as the “stop-time rule,” service of the NTA upon the noncitizen stops both of these clocks. Therefore, for noncitizens seeking to accrue the required periods of time, issuance of the NTA can be fatal to eligibility.

The litigation in Niz-Chavez built upon a similar case, Pereira v. Sessions, and examined the precise form that an NTA must take in order to trigger the stop-time rule. The Immigration and Nationality Act specifies 10 different pieces of information that together constitute notice of removal proceedings. In Pereira, the court held that NTAs lacking some of that information – specifically, the time and place of the hearing – are insufficient to trigger the stop-time rule. Pereira did not squarely answer the question presented in Niz-Chavez: whether the stop-time rule is triggered if the government provides notice via multiple documents – commonly, an NTA lacking time and place information, followed by a subsequent hearing notice. Petitioner Agusto Niz-Chavez had received precisely that kind of two-part notice before he had accrued 10 years of physical presence in the United States. The Board of Immigration Appeals and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit both held that Niz-Chavez was ineligible to apply for cancellation of removal because the two notices, taken together, had triggered the stop-time rule.

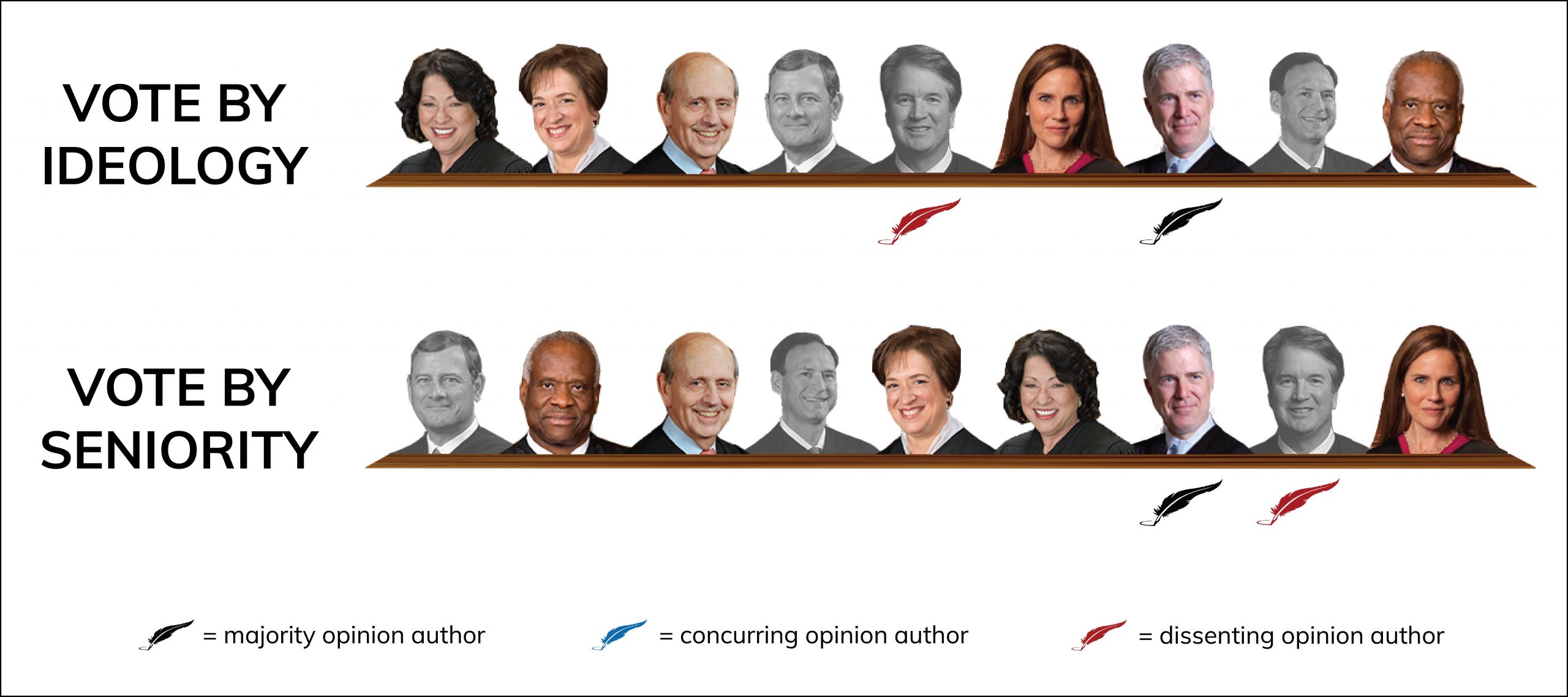

The majority opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch reverses the decision of the 6th Circuit and holds that all of the required notice information must be transmitted via a single document in order to trigger the stop-time rule. An unusual alliance of justices joined Gorsuch: the court’s three liberals – Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan – as well as two other conservatives – Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a dissent, which was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito.

While the majority rests its decision primarily on statutory interpretation, two broad themes animate the opinion. First, Gorsuch not-so-subtly telegraphs that the government should have learned its lesson in Pereira. Gorsuch notes the “outsized controversy” that the stop-time rule has generated, and laments that the government chose “to continue down the same old path” after Pereira. Second, the majority declines to accommodate the government’s desire for more flexibility in providing notice, especially when members of the public are held to exacting standards when completing government forms. What’s good for the goose, according to the six-justice majority, is just as good for the gander.

For the majority, Congress’ use of the indefinite article “a” in the stop-time rule signals its intent that the constituent information of the notice to appear be served via a single document. Specifically, INA Section 1229b(d)(1) notes that the stop-time rule is triggered “when the alien is served a notice to appear under section 1229(a).” Section 1229(a)(1), in turn, states that “written notice (in this section referred to as a ‘notice to appear’) shall be given … to the alien.” According to the majority, by using the indefinite article “a,” Congress conveyed its expectation that notice be provided via a single document at a fixed moment in time. In an effort to undercut the dissent’s reliance on the more ambiguous phrase “written notice,” the majority notes that even if that definitional phrase is substituted for “notice to appear” in Section 1229b(d)(1), the language still strongly suggests that a single document is required. As Gorsuch puts it, there is a “plain statutory command” that flows from the ordinary meaning of the terms.

The majority and dissent also spar about whether, and under what circumstances, an indefinite article might precede an item that could be transmitted via multiple parts. Gorsuch suggests that “a car” clearly cannot be delivered via its component parts, but Kavanaugh offers that items conveying information, such as a “a job application” or “a manuscript” might in fact be relayed in multiple pieces. According to the majority, however, the indefinite article “a” usually precedes countable nouns. Gorsuch also cleverly quotes the government’s oral argument in Pereira, when it analogized an NTA to an indictment or a complaint – pleadings which cannot be broken down into multiple pieces. The dissent counters once again, arguing that an NTA is distinguishable, in that it provides both charging and scheduling information.

To buttress its interpretation of the statute’s plain language, the majority also looks to neighboring INA provisions and to legislative history. Gorsuch identifies two sections of the INA – Sections 1229(e)(1) and 1229a(b)(7) – both of which use the phrase “the notice” in a way to suggest a single document is required. The majority also emphasizes that Congress affirmatively amended the INA to eliminate a past practice that allowed multi-part notice. Previously, the statutory provisions governing an order to show cause, the predecessor to the present-day NTA, permitted the government to serve time and place information separately from the order itself. But when Congress changed the name of the document in 1996, it deleted that more permissive language. Gorsuch also notes that the preamble to a 1997 regulation quite explicitly stated that time and place information must be included on the NTA.

Kavanaugh’s dissent seeks to poke holes in the majority’s reading of the statute and its legislative history. Seizing onto an argument made in the government’s briefing, he emphasizes that the statute itself defines “notice to appear” as “written notice,” the latter of which is not specifically framed as a single document. In an attempt to counter the majority’s structural arguments, Kavanaugh cites Section 1229a(b)(5) of the INA, which also uses the phrase “written notice” and which, according to the dissent, might reasonably contemplate multiple documents. As for the historical arguments, Kavanaugh dismisses the significance of the perambulatory language in the 1997 proposed rule, noting that the language of the rule itself required time and place information to be included only “where practicable.”

Beyond their respective readings of the statutory language and legislative history, the majority and dissent articulate different views of how to balance the need for bureaucratic flexibility with the interests of noncitizens. The majority is loath to cut the government any slack, fearing a slippery slope toward multiple, piecemeal notices that might be unintelligible for noncitizens with limited knowledge of English. The dissent suggests that the government has no incentive to issue such fragmented notices, but asserts that noncitizens might ultimately benefit from a two-part notice, as it would allow them additional time to prepare for their removal proceedings. Kavanaugh also catalogs a “litany of absurdities” that flow from the majority opinion, and he speculates about how the government might modify its practices in ways that disadvantage noncitizens. In one of the concluding passages, the dissent asserts, with limited support, that the court’s holding will further clog an overburdened immigration system with claims that are unlikely to succeed.

In an opinion that focuses heavily on the meaning of words, one additional semantic feature is noteworthy: the justices’ use of the term “alien.” The Biden administration recently ordered its immigration enforcement agencies to use the more neutral term “noncitizen” instead of “alien” – a term which pervades the INA yet which many consider to be dehumanizing. Notably, Kavanaugh’s dissent studiously avoids using the term “alien,” except when quoting statutory language. By contrast, Gorsuch, who held in favor of Niz-Chavez, uses the term more liberally. For a decision marked by unexpected alliances, the irony is fitting. But while noncitizens and their advocates might critique the majority’s use of outdated terminology, the ultimate outcome in Niz-Chavez – which holds the government to a stricter standard and expands access to an important form of relief – is one they will surely embrace.