A “view” from the courtroom: Wait, wait … there’s more

on Jun 25, 2018 at 3:23 pm

Today is the last day scheduled on the court’s calendar for the justices to take the bench. But most observers are not expecting the court to issue all six remaining merits opinions.

For one thing, although it was once routine for the justices to release as many as six opinions on a single day, the court generally sticks to fewer than that these days. For another, Chief Justice John Roberts this past Friday did not give the customary indication that today would be the last one and “at that time we will announce all remaining opinions ready during this term of the court.” (I mistakenly suggested in Friday’s “view” that it was Marshal Pamela Talkin who makes that statement, but as some astute readers reminded me, it is the chief justice.)

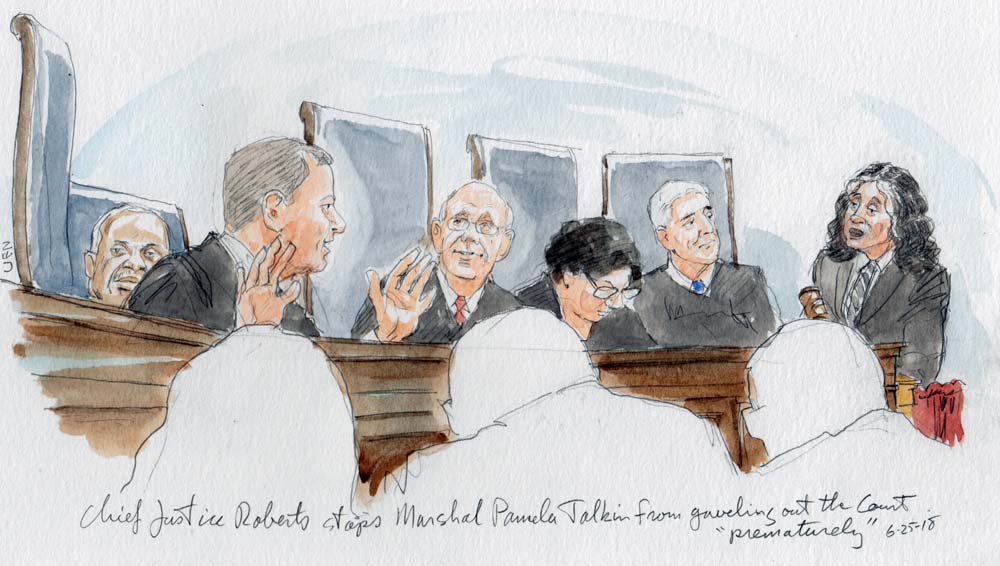

Chief Justice Roberts stops Marshal Pamela Talkin from gaveling out the Court “prematurely” (Art Lien)

Inside the courtroom, there is a growing number of interested observers — those awaiting the result in a particular pending case. In the center section of the public gallery, Illinois state worker Mark Janus is here, awaiting a decision in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Council 31, about whether public-employee unions may continue to collect agency fees from those members of a bargaining unit, such as Janus, who decline to join the union.

On Janus’ left is Gov. Bruce Rauner of Illinois, who launched the lawsuit that asks the court to overrule its 1977 decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. Rauner was found to lack standing in the matter, but Janus and two other state employees intervened, which allowed the case to make its way here, where Janus is the sole petitioner.

Also in the courtroom today are participants in the Supreme Court Summer Institute for Teachers, a joint effort of Streetlaw Inc. and the Supreme Court Historical Society. Two groups of teachers from around the country come to Washington for several days of instruction, a moot court at Georgetown University Law Center and various events at the court itself.

The case for moot court this year was Carpenter v. United States, about whether the government’s review of cell-site location information was a search under the Fourth Amendment. The court held that it was in most instances. The moot court justices of the teachers institute, however, ruled for the government, both in a session that occurred a week ago before the real Supreme Court had ruled, and in the second session this past weekend, after they had the additional resource of 118 pages of opinions from the real justices.

The VIP box looks pretty full this morning, but we see only one justice’s spouse—Joanna Breyer, the wife of Justice Stephen Breyer. In the press section, meanwhile, we have a guest whose face should be familiar to anyone who watched “The Fourth Estate,” the Showtime documentary series about The New York Times and its coverage of President Donald Trump’s first year in office. Michael Shear, a White House correspondent for The Times who appears prominently in the series, is helping the newspaper’s Supreme Court correspondent, Adam Liptak, who is down in the press room to receive opinions.

When the real justices take the bench at 10 o’clock, the chief justice settles in and appears ready to give his routine announcement that today’s orders have been duly certified and filed with the clerk. But his long, thin, adjustable microphone is tilted practically skyward, and Roberts looks askance at it momentarily before moving it down. At least two other such microphones on the bench are in the same position, as if someone had moved them to dust the desks and not returned them to the proper positions.

Roberts announces that Justice Samuel Alito has the opinion of the court in … and here Rauner and Janus perk up expectantly, because an Alito assignment in the Janus case would be good news for them. But it’s not the Janus case, it’s Abbott v. Perez, a racial-gerrymandering case from Texas (and a companion case with the same caption).

“The background of these case is somewhat complicated, but I will try to keep this summary relatively short,” Alito says.

He provides some of the background of this case that began with a 2011 remap of Texas congressional and state legislative districts, which led to a later plan that continues to be challenged for some racially gerrymandered districts.

Alito does fairly quickly summarize that the court’s holdings today, that the justices have jurisdiction to review the orders of the three-judge federal district court effectively barring the use of the plan in this year’s election, and that the district court erred in requiring Texas to show that the state legislature in 2013 had purged the taint that the court had attributed to the 2011 plan.

The court has never held that past discrimination “flipped the burden of proof on its head,” Alito says. Except with respect to one Texas House district, Alito says the district court erred in enjoining the use of the districting maps adopted by the state legislature in 2013.

Justice Clarence Thomas has written a concurring opinion, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch. Justice Sonia Sotomayor has written a dissent, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Breyer and Elena Kagan.

Justice Clarence Thomas is up next with the opinion in Ohio v. American Express Co., a big-ticket antitrust case over the credit-card company’s contractual provisions with merchants.

Like everyone else in the world, Thomas says he will refer to the company as “Amex for short.” The contractual provisions at issue prohibit merchants from discouraging customers from using their Amex cards at the point of purchase, a practice known as steering. Amex earns most of its revenue from merchant fees, which tend to be higher than those of its competitors, such as Visa, Mastercard and Discover, who collect fees from merchants but also interest from cardholders.

Amex was sued by the United States and several states, who argued that the anti-steering provisions in its contracts with merchants violate federal antitrust law.

Thomas concludes for the court that they do not. The two-sided platform in this area, involving merchants and cardholders, is still just a single market because only a company with both will to be able to participate in the market. And the challengers have not met their burden of showing anti-competitive effects because their argument that Amex’s anti-steering provisions increase merchant fees wrongly focuses on just one side of the market.

Among other things, Thomas says, “Amex’s competitors have exploited its higher merchant fees to their advantage,” such as by being more widely accepted.

Thomas wraps up quickly, noting that Breyer has filed a dissent, joined by Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan.

With that, before the chief justice says anything else, Marshal Pamela Talkin bangs her gavel, and court police officers begin to motion everyone to stand.

But wait. We’re apparently not yet done. Roberts interrupts Talkin and motions with his hands for all to remain seated. “Whoa, whoa,” he seems to say, then raising his hands to shoulder-height.

Breyer has a summary of his dissent to offer, and he starts delivering it even as there is still a small commotion of everyone settling back into their seats.

“The antitrust laws play a central role in our economic free-enterprise system,” he says. “This is a traditional Sherman Act, Section 1, antitrust case.”

He appears to ad lib the next line: “I don’t know if that excites you, but it is.”

Breyer provides his perspective on the anti-steering provision. Without such an agreement, a merchant might encourage a customer to use a lower-fee card, such as Discover, and might reward retail patrons with “a free shopping bag” or restaurant customers with “free butter.” (I’m not sure where Breyer dines where the butter costs extra.)

“But the merchant cannot do any of those things because of the nondiscrimination [or anti-steering] provision,” he says. “And the agreement thereby stops price competition in its tracks.”

He goes on at some length about the particulars of his dissent before seeking to put it in perspective. “I particularly fear the interpretive impact of the majority’s discussion of what it calls ‘two-side platforms,’ in an era when that term might be thought to apply to many internet-related goods and services that are becoming ever more important.”

“Just in case we’re wrong about everything I’ve said so far, and of course we’re not wrong,” Amex should still lose, Breyer says, before offering several reasons for that. (From the bench, he does not mention the term “laissez-faire capitalism”, which readers of the published slip opinion by this justice who sometimes delivers speeches in French are quickly pointing out is misspelled there as “lassez-faire.”)

More generally, he says, he wants to emphasize the importance of “traditional antitrust law,” which “insists on a freely competitive marketplace.”

“It has long helped this nation prosper by charting a middle path between monopoly capitalism and state economic control,” Breyer says. “Long gone, we must hope, are the days when great trusts unfettered by competition presided over the American economy.”

After a few more closing words, Breyer is finished, and so is the court for today.

With a slight smile on her face, Talkin bangs her gavel again, and says, the “honorable court is now adjourned until tomorrow at 10 o’clock,” with some emphasis on “now.”

And Roberts has not delivered the second-to-last day comment, so it appears there are two more opinion days for the four remaining opinions.

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is among the counsel on an amicus brief in support of the petitioners in this case. However, the author of this post is not affiliated with the firm.]