Empirical SCOTUS: Interpretive dance

on Mar 28, 2018 at 12:53 pm

In the Supreme Court’s first decision of the term, Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg cited language from the court’s 2010 decision in Magwood v. Patterson stipulating that “[w]e cannot replace the actual text with speculation as to Congress’ intent.” Indeed, as Justice Elena Kagan wrote in the 2015 decision Ross v. Blake, “[s]tatutory interpretation, as we always say, begins with the text.” Even with this prescription, however, the justices often disagree on how to interpret various statutes and code sections enacted by Congress. This post looks at the methods of interpreting these texts employed by the justices so far this term (this excludes the interpretation of federal rules as in Hall v. Hall and Class v. United States). It looks at the justices’ stylistic differences as well as differences on a case-by-case basis.

Although the justices often say the plain meaning of text is dispositive in their decision-making, the ways they reach outcomes take divergent paths. One difference between the justices relates to the methods of interpretation they are willing to employ. Linda Greenhouse expounded on this point in a recent New York Times piece, in which she examined Justice Antonin “Scalia’s Fading Legacy” regarding the Supreme Court’s willingness to use legislative history in interpreting statutes. During Scalia’s tenure on the court, legislative history was generally only mentioned in opinions as an aside and with various caveats such as, “for those who care about it,” as used by Kagan in her dissent in Yates v. United States. Even recently, Justice Neil Gorsuch described legislative history in similar terms in Murphy v. Smith (“[e]ven for those of us who might be inclined to entertain it, Mr. Murphy’s legislative history…”) Still, as Greenhouse notes, legislative history has made its way into decisions like the one in Digital Realty Trust v. Somers with more legitimacy than it had in prior years with Scalia on the court.

Now with Gorsuch on the court, one of the many interesting areas to watch is how the court’s interpretive tools will shift, if at all. Although many acknowledge Gorsuch’s prowess at interpretation, his pedantic style tends to dominate discussions, overshadowing even his thoughtful evaluation of statutes.

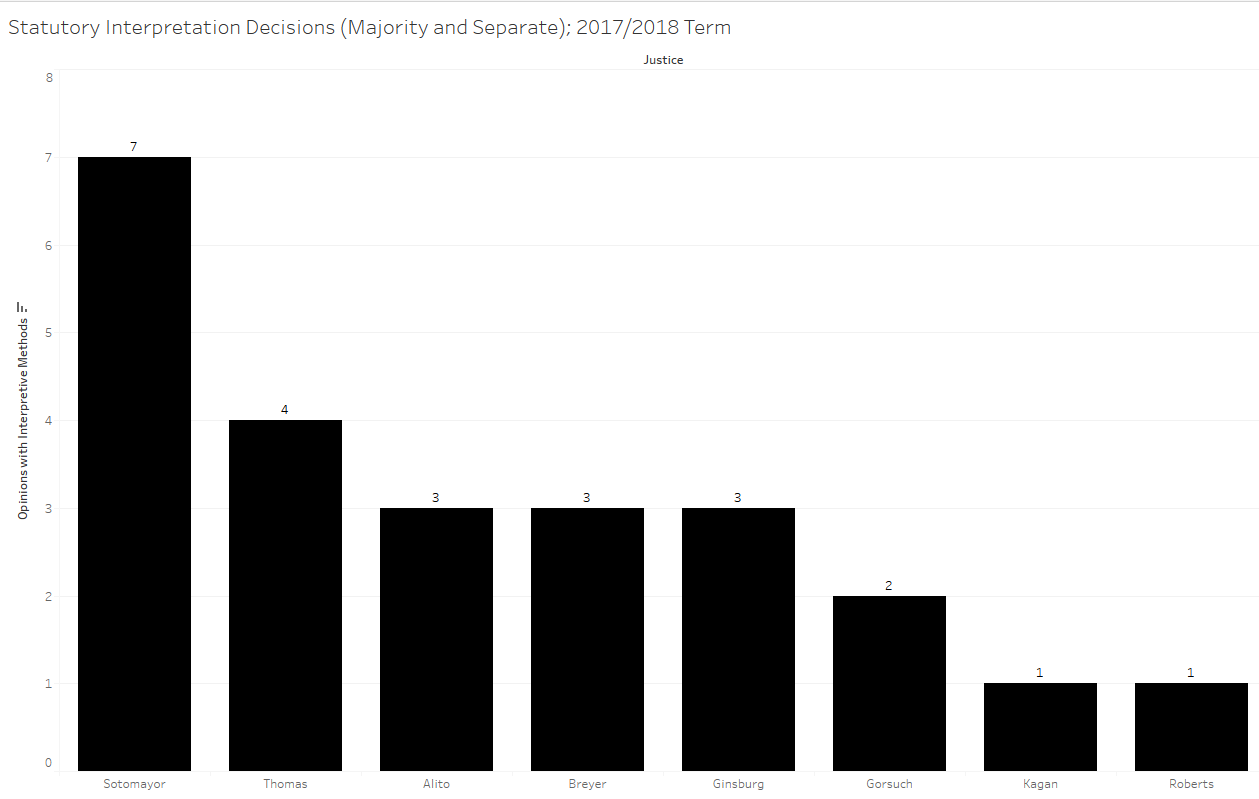

So how have the justices differed so far this term? First, a look at the number of combined majority and separate opinions authored by the justices so far this term in which such interpretive methods were employed.

The 12 cases in which the justices have relied on statutory interpretation in their decisions this term include Artis v. District of Columbia, Jennings v. Rodriguez, Ayestas v. Davis, Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, Digital Realty, Marinello v. United States, Merit Management Group v. FTI Consulting, Murphy v. Smith, National Association of Manufacturers v. Department of Defense, Patchak v. Zinke, Rubin v. Iran, and U.S. Bank v. Village at Lakeside. In Hamer, Ginsburg examined the statute that preceded the rule at issue in the case, although the decision relates to the rule and not the statute.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote majority opinions in the most cases in this set among the justices, with three (Merit Management, NAM and Rubin). She interpreted statutes in four separate opinions as well, which is the greatest number among the justices. Justices Ginsburg, Samuel Alito and Kagan each authored two of these majority opinions, with Alito authoring the decisions in Jennings and Ayestas, Ginsburg in Digital Realty and Artis, and Kagan in Cyan and U.S. Bank. Justices Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas and Gorsuch each authored one of these majority opinions apiece, in Marinello, Murphy and Patchak respectively. The two justices who tend to author many of the significant decisions later in the term, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy, have yet to write the majority opinion in a statutory interpretation case this term.

Within the cases, I focused on particular language referencing a method of interpretation as well as the number of times justices employed such methods. I excluded instances in which justices used a method of interpretation to rebut a point or say that someone else looked at a statute in such a fashion (e.g., in a lower-court opinion).

The two cases this term with likely the largest disputes among the justices centering on how to interpret statutes were Jennings and Murphy v. Smith. In Jennings, Breyer and Alito mainly engaged in debate regarding whether specific sections of the U.S. Code give detained aliens the right to periodic bond hearings during the course of their detention.

Alito attempted to focus on the plain meaning of the text of the code sections, with language like, “[t]he plain meaning of those phrases is that detention must continue” and “[b]y expressly stating that the covered aliens may be released ‘only if’ certain conditions are met, 8 U. S. C. §1226(c)(2), the statute expressly and unequivocally imposes an affirmative prohibition on releasing detained aliens under any other conditions.” Alito also attempted to use the text to rebut points made by the respondents and adopted by the dissent. Some examples of this are: “[d]espite the clear language of §§1225(b)(1) and (b)(2), respondents argue—and the Court of Appeals held—that those provisions nevertheless can be construed to contain implicit limitations,” and “[t]hat interpretation [by respondents] is inconsistent with ordinary English usage and is incompatible with the rest of the statute.”

Breyer, on the other hand, used a wider array of interpretive methods. To this effect he wrote, “In my view, the relevant constitutional language, purposes, history, tradition, and case law all make clear that the majority’s interpretation at the very least would raise ‘grave doubts’ about the statute’s constitutionality.” In fact, one of the focal points in his dissent is seeking to avoid a finding that the statute is unconstitutional as he says, “I would follow this Court’s longstanding practice of construing a statute ‘so as to avoid not only the conclusion that it is unconstitutional but also grave doubts upon that score.’”

While on balance in these cases the justices often discussed the plain meaning of statutes, the majority of references to methods of statutory interpretation so far actually focused on examining statutory context. Sotomayor provided several examples of this in NAM when she wrote, “The statutory context makes clear that the prepositional phrase—’under section 1311’—is most naturally read to mean that the effluent limitation or other limitation” and “whether it does so necessarily depends on the statutory context, and the word ‘any’ in this context does not bear the heavy weight the Government puts upon it.”

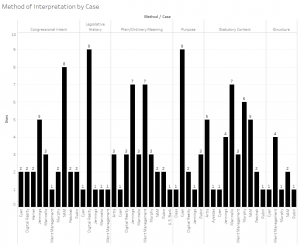

Using specific formulations of six methods of interpretation, I looked at how frequently the methods were used in this term’s cases so far. The focal points for interpretation and words I looked for were “context,” “plain,” “ordinary,” “purpose,” “history” and “structure.” When I located the use of such a term, I looked to see if the reference related to a statute. Below are the numbers of times a method of interpretation was invoked in an opinion.

Statutory context, plain meaning and congressional intent were utilized most frequently. The justices employed legislative purpose, structure and history a number of times, although to lesser degrees than the other methods.

Sotomayor, along with employing these methods of interpretation more often than the other justices so far this term, also used a diverse set of tools to interpret the statutes at issue in the cases. The following chart breaks down the uses by case and justice.

Sotomayor often explored legislative purpose and context and was not opposed to examining legislative history. Perhaps not surprisingly for those who follow such things, the four justices who found legislative history helpful in interpreting statutes so far this term were those on the Supreme Court’s left wing. Alito, Gorsuch and Thomas were much more prone to focusing on plain meaning and occasionally on statutory context.

The next chart shows how often the different methods were described by case.

To highlight some of the cases and methods: Congressional intent was mentioned most frequently in Murphy v. Smith, legislative history in Digital Realty, plain meaning in Jennings and Merit Management, legislative purpose in Cyan, statutory context in Marinello, and a statute’s structure in Merit Management.

Quite a diverse set of tools helped shaped the outcomes in cases so far this term. On this post-Scalia court it will be interesting to see how the justices’ tools of statutory interpretation change, if at all. Gorsuch has already engaged in significant statutory interpretation while on the Supreme Court and appears to have a hierarchy of interpretive methods similar to those of Thomas and Alito. If the separation between the court’s liberal and conservative justices on which methods of interpretation are valid continues unabated, we may well see contentious dueling interpretations in the weeks and months to come.

This post was originally published on Empirical SCOTUS.