Opinion analysis: A narrow, but unanimous, ruling on Arizona redistricting

on Apr 20, 2016 at 2:21 pm

In June 2015, the Supreme Court announced that it would review a challenge to the redistricting map drawn by Arizona’s independent redistricting commission. The plaintiffs in the case, a group of Arizona voters, argued that the commission had not distributed Arizona residents evenly among the state legislative districts: it put too many people in some Republican districts, while it put too few in some Democratic districts. This wasn’t a coincidence, the voters claimed. Instead, they contended, the commission drew the districts this way to help the Democratic Party – partisan gerrymandering, in other words. With the Court having announced just a month earlier that it would also take on a case alleging that Texas had violated the principle of “one person, one vote” in drawing its own legislative maps, some wondered whether the two cases might lead to a seismic shift in the Court’s voting rights jurisprudence.

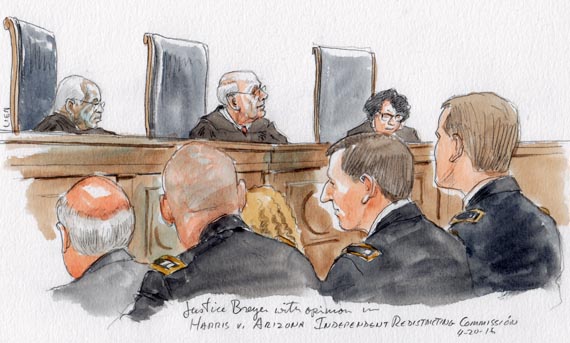

Or not. On April 4, a unanimous Court upheld the Texas voting map. And this morning, the Court – in an opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer that barely made it on to the eleventh page – unanimously upheld the Arizona one as well.

In his opinion for the Court, Breyer explained that the Constitution requires states to try to distribute residents evenly among legislative districts, but it “does not demand mathematical perfection.” In particular, states can draw districts with populations that aren’t perfectly equal if there is a good reason to do so – for example, to draw districts that are compact or to ensure that a city or county is not split up. And the fact that districts aren’t perfectly equal, standing alone, does not mean that a redistricting map violates the Constitution, Breyer explained, if the largest deviation from perfect equality is less than ten percent.

When, as in this case, the deviation is less than ten percent, plaintiffs like Wesley Harris and his fellow voters must meet a more difficult standard: they must show that “it is more probable than not” that the deviation is attributable to some other, illegitimate reason. And, the Court concludes, Harris cannot do so here. When the commission was drawing the maps after the 2010 census, its primary consideration was whether the maps would comply with the federal Voting Rights Act. Among other things, that act prohibits new redistricting plans that would decrease the number of districts in which minority groups can elect candidates of their choice. The evidence in the case, the Court reasons, reflects that any deviations from equally populated districts were largely attributable to the commission’s efforts to make sure that the plan contained enough of these “ability to elect” districts to pass muster under the Voting Rights Act.

But, the voters had protested, party politics must have entered (improperly) into the mix: after all, virtually all of the Democratic districts have populations that are lower than they would be if all districts contained the same number of people – which would give more voting power to the residents in those districts – while most of the Republican districts have populations that are greater than they would otherwise be, giving those residents less voting power. The Court seemed to regard this as a matter of correlation, rather than causation, though. Noting “the tendency for minority populations in Arizona in 2010 to vote disproportionately for Democrats,” it suggested that, in its efforts to ensure that it had enough “ability to elect” districts to comply with the Voting Rights Act, that the commission may have had to move “other voters out of those districts, leaving them slightly underpopulated.”

The Court also rejected out of hand the suggestion that, because Arizona is no longer required to obtain approval of its redistricting maps from the federal Department of Justice, a desire to comply with the Voting Rights Act could not have been a good reason to draw districts with unequal populations. The Court didn’t issue its decision in Shelby County v. Holder, striking down the formula used to determine which state and local governments need to get preapproval from the Justice Department, until 2013, while the commission created the redistricting plan at issue in this case in 2010. And so even if Arizona doesn’t need to get preapproval now, the Court stressed, it did in 2010 – which is all that matters for this case.

Both the brevity of today’s opinion and the text itself seem to suggest that the decision is a relatively narrow one. When a state or local government draws a redistricting map that does not distribute the population completely evenly, but still keeps the deviations from perfect equality under ten percent, the map can still survive unless the challengers can show that something more nefarious was going on. Exactly how nefarious that conduct must be is an open question, but the Court’s opinion strongly indicates that challenges will succeed “only rarely, in unusual cases” – a high bar indeed.