ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

In dispute over discovery requests in international arbitration, justices weigh text, comity, academic literature, and their own role

on Apr 29, 2022 at 10:51 am

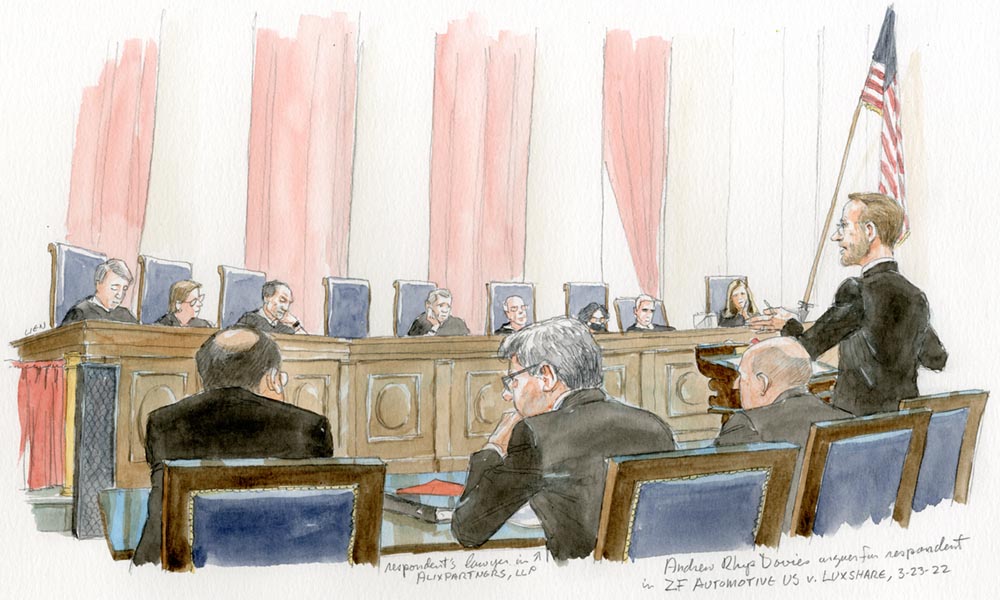

On March 23, the Supreme Court considered the appropriate scope of 28 U.S.C. § 1782, which authorizes a federal district court to compel individuals and companies within its jurisdiction to provide discovery to proceedings pending in “foreign and international tribunals.” In an oral argument that lasted almost two hours over two consolidated cases, ZF Automotive US Inc. v. Luxshare Ltd. and AlixPartners LLP v. The Fund for Protection of Investors’ Rights in Foreign States, the justices wrestled with whether private commercial arbitrations and bilateral investment treaty arbitrations qualify as tribunals within the meaning of the statute.

The first case involves the application by a Hong Kong company, Luxshare, Ltd., to obtain discovery from ZF Automotive US, a Michigan subsidiary of a German corporation. Luxshare wants to use the information in a private commercial arbitration proceeding in Germany to demonstrate that it had been fraudulently induced to sign a contract. Because the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit had previously ruled in a binding precedent that private commercial arbitration panels are “foreign tribunals” for purposes of Section 1782, a district court in Michigan granted Luxshare’s application. The Supreme Court agreed to review the decision before the 6th Circuit completed its appellate process, presumably in recognition of a circuit split on this issue.

In the second case, the government of Lithuania allegedly expropriated the investment of a Russian national in a Lithuanian bank. The Russian investor (known as The Fund for Protection of Investors’ Rights in Foreign States) invoked a pre-existing bilateral treaty that gives the national of one country the option to seek arbitration against the other country for discriminatory official treatment. The treaty does not establish a standing arbitral body. Instead, the claimant must elect to proceed in one of the three established private arbitration centers or initiate an ad hocarbitration under the rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. The fund sought discovery from AlixPartners, which had served as bankruptcy receiver for the bank. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit held that the arbitration is sufficiently state-sponsored to fall within the ambit of Section 1782.

During oral argument, the justices and advocates parsed the questions from multiple perspectives, including the plain text of the statute, the degree of governmental involvement required, comity, the appropriate role for the judiciary, and the relevance of academic literature.

Plain text of the statute

ZF did not achieve a knock-out win based on the plain text of the statute. Its counsel, Roman Martinez, tried to argue that two words in the phrase “foreign tribunal” had to be read together to require a governmental affiliation for the arbitration tribunal. He pointed out that while one may think of the leader of the Manchester United soccer club as a leader based in a foreign country, he is not a “foreign leader” in the vernacular sense.

But Chief Justice John Roberts was not persuaded. He suggested that “tribunals” mean adjudicatory bodies and that “foreign” merely refers to where the body is established. He further said “foreign” is not a “gratuitous word that can only convey the notion of governmental.” The chief justice expressed support for the view that a private arbitration center that is located in (for example) France should be considered both a tribunal and foreign, thereby meeting the definition of “foreign tribunal” even though it lacks a governmental connection.

Justice Elena Kagan likewise opined that any college located abroad would qualify as a “foreign university,” even if the school is privately run. Justice Brett Kavanaugh then also expressed skepticism that the court should artificially combine the two words to get the meaning that ZF desires, as opposed to reading the words separately.

Nor did Martinez make much headway using the corpus linguistics methodology. This technique involves electronically analyzing large bodies of text to detect linguistic patterns of use. According to Martinez, a study using this technique demonstrated that the term “foreign tribunal” meant only an entity exercising governmental authority to resolve a dispute. But Roberts said he was not sure “what to make of that” and that he had not relied on the method before in interpreting a statue. Justice Amy Coney Barrett then jumped in to clarify that the court itself had never embraced this method as a tool of statutory construction.

Degree of governmental involvement

There were meandering and ultimately inconclusive discussions on the level of governmental involvement that would be sufficient to meet the requirements of Section 1782, assuming that some governmental involvement is required. When asked by Kavanaugh whether arbitrators themselves must be appointed, paid for, or removable by the government, Martinez did not give a direct answer. Joseph Baio, counsel for AlixPartners, on the other hand, proposed that to qualify as a tribunal under Section 1782, there must be a standing arbitral body and the arbitrators must be governmental officials. Under that theory, the Russia-Lithuanian arbitration would fall outside of Section 1782.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor pushed back and said that she had a “very hard time understanding that distinction.” She did not see an issue with a treaty giving an investor (as opposed to a state) the ability to select arbitrators because ultimately that ability to choose flows from “an agreement between two sovereign nations to submit a dispute that could involve both of them in an adjudicatory body that they have created.” Kagan likewise indicated that she did not see a meaningful distinction between a standing system (which arguably exists under the Russia-Lithuania treaty) and a standing body (which is lacking). Addressing Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler, who argued on behalf of the federal government in support of the petitioners, Sotomayor continued to express her skepticism, stating that she did not understand why the court should insist on the “formality” of a standing arbitral commission.

There was also discussion of three past international government commissions involving the United States: the Jay Treaty commission after the American Revolution, a mixed claims commission set up after World War I to resolve claims with Germany, and a U.S.-Canada commission set up to resolve maritime border disputes. Because Congress no doubt had these commissions in mind when it enacted the term “international tribunals,” the petitioners made the case that only a substantially similar international body would fall within the scope of Section 1782.

Arguing for The Fund for Protection of Investors’ Rights in Foreign States, Alexander Yanos emphasized that when government officials served on those commissions they were not doing so in their official capacity. “They were arbitrators. They were sitting in a dispute effectively private between two sovereigns.” More fundamentally, Yanos tried to get his fact pattern closer to that of those examples by emphasizing that the fund was standing in the shoes of the government of Russia. He contended that Lithuania allegedly violated its treaty obligation of fair treatment to Russia, not to his client. Historically the Russian government would have taken up his client’s cause directly with the government of Lithuania, either through a quasi-legal process or using tools of diplomacy. Indeed, in the Jay Treaty commission process, the U.S. government asserted and settled claims for American citizens whose property was damaged by British forces during the war. Here, in the modern commercial age, the two governments agreed that the fund could proceed directly with a legal claim against the government of Lithuania. This modern innovation in which the Russian government takes a much attenuated role should not make the arbitration proceeding less official.

Comity

The Supreme Court generally takes the executive branch’s views on comity seriously, and Wheeler’s presentation focused heavily on that theme. A central purpose of Section 1782 was to convince foreign governments to enact similar laws. But, Wheeler argued, because foreign arbitral tribunals have no authority to reciprocate, this rationale is on the surface not applicable here. Counsel for respondents countered that foreign governments have themselves invoked Section 1782. In addition, major arbitral centers, including the United Kingdom and France, have reciprocated by providing discovery assistance for international arbitration.

Wheeler also argued that the use of Section 1782 discovery in investor-state arbitrations would undermine comity and create foreign policy friction by subjecting foreign governments to Section 1782 proceedings. But because foreign governments are already subject to this statute when they are parties to court proceedings, it is not clear if this concern is genuine. In fact, most bilateral investment treaties give an aggrieved party the option to proceed in a court or in an arbitral forum. If the Supreme Court excludes investor-state arbitrations from Section 1782, an aggrieved investor could still subject a foreign government to a Section 1782 proceeding by proceeding in court.

Should the court defer to Congress?

When the current version of Section 1782 was enacted in 1964, international arbitration (both private and investor-state) as we know it today did not exist. Several justices expressed concern about whether they should presume to make a policy judgment that should be rendered in the first instance by the political branches, given the foreign policy implications and the potential to create significant new work for the federal district courts. As Justice Stephen Breyer pointed out, users and targets of Section 1782 are sophisticated companies capable of lobbying Congress, which may be the most suitable forum for resolution of the dispute.

The position of the Restatement

American Law Institute’s Restatement of the U.S. Law of International Commercial and Investor-State Arbitration, which was written by some of the country’s most preeminent scholars on the subject, takes the unequivocal position that Section 1782 covers both private arbitration and investor-state arbitration. This academic view has made a strong impression on Breyer. He said at one point that he is “having trouble with this case” because the federal government and the scholars take completely divergent views.

Conclusion

Given the competing considerations, this is clearly not an easy case for the court. Oral argument did not shed light on which direction the court is leaning. If the Supreme Court were to affirm the decisions below, it would most likely craft a legal test to ward off abusive practices and to ensure that discovery for arbitration proceedings is manageable for the district courts. If the court were to reverse the decisions below, it would most likely invite Congress to resolve the issue. A decision, eagerly anticipated by the international business community, should be announced by June.

Correction (May 11 at 9:50 a.m.): An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the lawyer who argued on behalf of the The Fund for Protection of Investors’ Rights in Foreign States. The lawyer is Alexander Yanos.