ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

Court seeks to protect judicial remedies in case challenging lethal injection

on Apr 27, 2022 at 2:48 pm

The Supreme Court heard oral argument on Monday in Nance v. Ward, considering which of two procedural vehicles should be used to challenge Georgia’s planned execution method (lethal injection). When must state prisoners alleging unconstitutional execution methods use habeas corpus petitions, and when may they proceed under the more general civil rights statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1983? If a state prisoner must use habeas litigation, then federal courts will almost never reach the merits of the claim. Georgia wants the court to prohibit the Section 1983 litigation, but the state seemed to have a formidable skeptic: Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

First, some background on the case. Habeas corpus relief is severely restricted, so the Supreme Court has drawn a careful line between conditions-of-confinement claims that proceed under Section 1983 and other challenges to detention that must go forward under the habeas statutes. If a prisoner seeks relief that would necessarily invalidate a sentence, then habeas is the only remedial option. Claims that must go through the habeas pathway are said to be “Heck-barred.” Without something like a Heck bar, state prisoners could evade habeas restrictions simply by styling their constitutional challenges as Section 1983 claims.

Method-of-execution litigation has long taken place under Section 1983 on the theory that the underlying challenges were to sentence implementation rather than to the validity of the sentences themselves. When the Supreme Court decided Bucklew v. Precythe in 2019, however, it generated a new question. Bucklew required prisoners who challenge execution methods to plead “feasible and readily implemented” alternatives, but it also held that those alternatives need not be presently authorized under state law.

In this case, Michael Nance indicated a firing squad as the alternative, but Georgia doesn’t authorize a firing squad. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit held that the claim was Heck-barred. It reasoned that, because no statutorily authorized alternative would survive a decision against Georgia, the requested relief would necessarily invalidate the death sentence. Nance, with an assist from the United States, argues that his requested relief would leave the death sentence intact — there would be no resentencing, and the execution could proceed in some other way — and so the claim isn’t Heck-barred. Nance further argues that, even if the method-of-execution challenge is treated as a habeas claim, it avoids the restriction on “successive” habeas petitions.

Questioning by the three “median” justices— Chief Justice John Roberts, plus Kavanaugh and Justice Amy Coney Barrett — provided some clues. And of the three, Kavanaugh was the least comfortable with Georgia’s position. Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan appeared to line up behind Nance. Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch appeared to lean the other way, and any state-prisoner claimant faces an uphill battle to secure Justice Clarence Thomas’ vote.

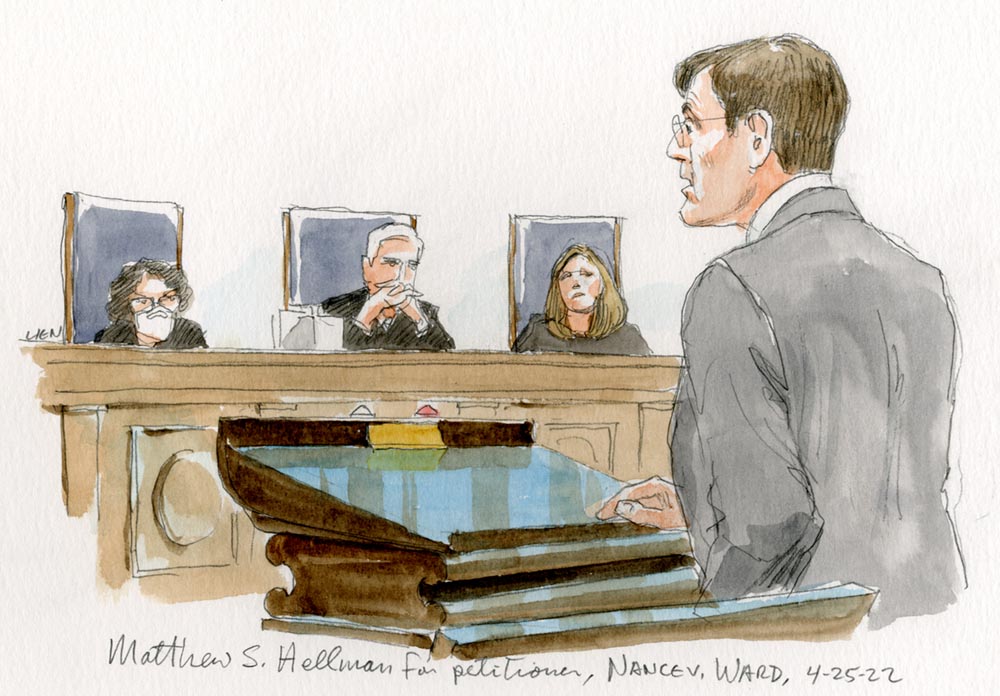

Matthew Hellman argued for Nance. Hellman fielded early variations of a question that would surface throughout oral argument: Does the analysis change if the judgment itself incorporates a specific method of execution. Hellman conceded that a method-of-execution claim implicating such a judgment might be Heck-barred, but underscored that Georgia death sentences specify no particular execution method. U.S. Assistant to the Solicitor General Masha Hansford gave a similar answer during her allotted time.

Assistant to the Solicitor General Masha Hansford argues for the federal government. (Art Lien)

Alito also posed another question that recurred throughout the morning. He wanted to know whether the analysis changed depending on the institutional response necessary to authorize the indicated alternative. He wanted to know whether the Heck bar might apply if the Georgia constitution were to identify lethal injection as the only permissible execution method. Hellman stated that the result would be unchanged, and that the litigation could proceed under Section 1983. Hansford later reinforced that position, insisting that the institutional response necessary to accommodate the indicated alternative did not change the equation — even though it might affect the merits analysis.

Kavanaugh had concurred in Bucklew to emphasize that the feasible-and-readily-implemented-alternative requirement would not always leave prisoners at the mercy of a state’s decision about which execution methods to authorize. He referenced his Bucklew concurrence during argument, and he seemed particularly concerned that Georgia’s position would undo what he considered to be Bucklew’s carefully crafted remedial balance. He called attention, for example, to the fact that Nance had lost in district court on timeliness, notwithstanding the fact that the district court analyzed the challenge as a Section 1983 claim. Kavanaugh seemed to believe that judges have the tools they need to deal with procedurally tainted method-of-execution claims, even under Section 1983. Kavanaugh’s early questioning of Georgia Solicitor General Stephen Petrany was particularly revealing: “We’ve been on a 15-year effort to organize how these method of execution claims should proceed, culminating in Bucklew. … My question is why would we upset all of that and create new complications.”

Petrany consistently invoked the purposes of the habeas statute to parry concerns that Georgia’s preferred rule would throttle remedies — including concerns expressed by the chief and Barrett. Petrany argued that the 1996 habeas legislation codified a powerful preference for state-court remediation, and that state remedies were sufficient to protect the underlying Eighth Amendment right. For example, Petrany relied on the idea of legislative purpose to argue that there need not be a federal remedy in cases where states change execution methods many years after the initial round of federal habeas litigation concludes. Per Petrany, the Section 1983 claim would be Heck-barred and the federal habeas statute would preclude successive litigation, but the remedial vacuum is nothing more than a consequence of intentional legislative design.

Toward the end of the argument, Petrany appeared to take a wrong turn in response to a line of questioning about the Supreme Court’s recent “spiritual adviser” cases. (These cases, including Ramirez v. Collier, involve Section 1983 claims contesting restrictions on spiritual advisers in execution chambers.) Kavanaugh, with some follow-up by Barrett, asked Petrany whether the spiritual adviser cases had been wrongly decided under a Section 1983 rubric. After Petrany said those claims should have gone through habeas — implying that they had indeed been decided in violation of the Heck bar — Kavanaugh gave Petrany an ominous signal. “Don’t take it the wrong way,” he said, “but if you were to lose this case, is it better for the state of Georgia to lose on the 1983 point or the second or successive point?”

Kavanaugh’s parting question probably indicates where the Supreme Court will go. It might decide that the claim is Heck-barred, but it is unlikely to thereafter hold that the habeas claim is impermissibly successive. Too many of the justices seemed too resistant to a legal rule that would largely extinguish federal remedies. But what would Nance win under such a decision? The restrictions on Section 1983 litigation are themselves formidable. Courts are willing to declare claims untimely even though earlier litigation would have required prisoner claimants to guess as to the eventual method of execution. Indeed, the district court did that very thing in Nance’s case. If Nance prevails, it might be that he wins nothing more than the opportunity to lose in a different way.