CASE PREVIEW

Florida and Georgia face off again in long-running fight over water rights

on Feb 19, 2021 at 5:29 pm

On Monday, the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear Florida v. Georgia, round two. At issue is whether the court will require Georgia to cap its water use in the Apalachicola River system and allow more water to flow downstream into Florida. Georgia says its water use is reasonable and insists that a cap would severely harm the Atlanta metropolitan area and the state’s agricultural industry. Florida says that Georgia is using far more than its fair share of the water, depleting flows into the Apalachicola Basin and wreaking havoc on Florida’s oyster fisheries.

Because the dispute is between two states, it falls under the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction – meaning it has not been litigated in the lower courts. Critical to the case are reports by two different court-appointed special masters, as well as thorny questions of evidence and the addition of two new justices since the last time this case was before the court in 2018. Given the special master’s most recent report and the acting U.S. solicitor general’s recommendations, Florida faces a challenge to prove its case for an “equitable apportionment” decree.

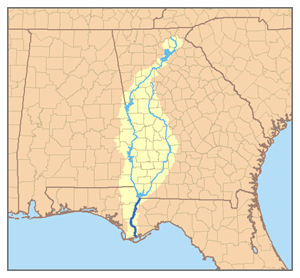

The Apalachicola River system stretches from northern Georgia through the Florida panhandle. (Pfly via Wikimedia Commons)

Monday’s argument comes more than seven years after Florida originally submitted its leave to file a bill of complaint in 2013. The court appointed Special Master Ralph Lancaster to oversee the dispute in November 2014. Lancaster conducted a lengthy trial in 2016 and issued his report in February 2017, rejecting Florida’s argument that Georgia’s water consumption should be limited. He concluded that Florida had “not proven by clear and convincing evidence” that putting a cap on Georgia’s water consumption would improve flows during a drought. Further, because the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dams and reservoirs in this river system, was not a party to the case, he found that Florida could not receive the relief it requested.

The Supreme Court reviewed Lancaster’s report, issuing a 5-4 decision on June 27, 2018 — the last day of its term — holding that Lancaster had applied too high of a standard of review for redressability and noting that the U.S. Army Corps “will work to accommodate” a decree. After listing specific questions to be addressed, the court remanded the case for further review. Since that decision, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett have replaced Justices Anthony Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg (both of whom were in the five-justice majority in 2018).

In August 2018, Lancaster “was hereby discharged with the thanks of the Court” in favor of a new special master, Judge Paul Kelly of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. After a swift start and then somewhat delayed proceedings, Kelly heard oral argument on Nov. 7, 2019.

Just over a month later, Kelly submitted a lengthy report to the court. He declined to decide whether Florida had to meet a standard of clear and convincing evidence, and he issued a report in Georgia’s favor. Kelly found that a preponderance of the evidence (a lower standard) supported his conclusion that the benefit to Florida would not outweigh the harm to Georgia by limiting the latter’s water use.

The court distributed the report for conference on Jan. 24, 2020, and after both states filed their briefs, the court scheduled oral argument for Feb. 22, 2021.

Florida’s arguments

On April 13, 2020, Florida filed its “Exceptions to the Second Report of the Special Master,” asking the court not to adopt Kelly’s recommendations and to overrule Kelly’s “refusal to allow additional evidence” about circumstances beyond the 2016 trial.

Florida emphasizes that even after the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision, “this case is in more need of this Court’s attention than ever.” Florida notes that Kelly held a single one-and-a-half-hour hearing, then issued a report “that flipped Special Master Lancaster’s core conclusions” and “rewrote this case from the ground up” through a “series of cascading errors.”

After reviewing the factual background of the case, Florida argues that the court should provide an equitable apportionment to protect “both States’ right to reasonable use of the waters.” Florida emphasizes that Lancaster found Florida “had suffered real harm from decreased flows, especially as to Apalachicola’s oysters, and that Georgia’s unrestrained consumption was unreasonable” but that relief was denied “because there was ‘no guarantee’ that the Corps would facilitate a decree.” Florida then cites the court’s 2018 decision, which stated that “an equity-based cap on Georgia’s use of the Flint River” – which flows south through Georgia and converges with another river at the Florida border to form the Apalachicola River – “would likely lead to a material increase in streamflow.”

Florida laments that the case “went awry” under Kelly: He refused to hear more evidence, dismissed Lancaster’s conclusions, found that Georgia’s water consumption was reasonable and had not harmed Florida, and asserted that the Corps would not accommodate a decree. Throughout its request for exceptions, Florida also argues that Kelly incorrectly dismissed its evidence and experts in favor of Georgia’s evidence and experts.

Florida asks the court for de novo review, noting that “this Court defers to no one” in resolving equitable apportionment cases over water between states. Florida argues that the court’s 2018 decision required an “equitable-balancing inquiry” and a determination of the extent of harm with deference to the previous findings. The court never suggested that a new special master should “start from scratch.”

Florida maintains that it has already been harmed by Georgia’s water consumption, with particular impact to oyster fisheries. Florida says the “chain of causation” is “hardly novel,” and is like the seminal equitable apportionment case New Jersey v. New York, an early 20th century decision about water flow and salinity impacts in the Delaware River system. Because Kelly’s finding on harm was “erroneous,” his entire balancing analysis was “corrupted,” the state argues.

Florida also says Georgia’s water use “has been unreasonable and unrestrained,” and that Georgia officials acknowledged the need to limit irrigation but failed to take adequate action. Florida disagrees with Kelly’s finding that “Georgia’s use is ‘not unreasonable,’” characterizing his conclusion as contradicted by evidence and compounded by errors.

Reinforcing its argument under the equitable-balancing inquiry, Florida states that it is entitled to a decree apportioning the water in the Apalachicola Basin and reasons that increasing the streamflow by even 1,000 cubic feet/second “would help facilitate meaningful recovery.” Florida revisits the issue of the Corps’ involvement, noting the flexibility implied by the court’s 2018 decision. Florida argues that Kelly “wiped out the benefits” while “overstating the costs” to Georgia of reducing wasteful and inefficient water uses, enforcement and other measures. In addition, Kelly erred because he assumed that Florida wanted irrigation in Georgia to be eliminated; rather, Florida proposed “reasonable limits,” thus changing the cost assumptions.

Florida closes by emphasizing the court’s authority — not that of the special master — to decide the case and the “commonsense principle that all States have an equal right to the reasonable use of shared resources.”

Georgia’s arguments

After receiving an extension, Georgia replied on June 26, 2020. Georgia provides its own view of the facts and proceedings on remand before making five arguments: (1) Kelly followed the court’s instructions by issuing factual findings on all relevant issues; (2) Florida failed to prove that Georgia caused Florida harm; (3) Kelly correctly found that Georgia’s water use was reasonable; (4) the benefits of a decree would not outweigh the costs; and (5) Florida cannot obtain a decree without proving its case on the merits.

Georgia begins with a pointed statement: After more than six years of litigation, “it is now clear that Florida’s case was built on rhetoric and not on facts.” Because Lancaster limited his findings to a single discrete issue — whether he could issue a finding absent the Corps’ involvement — Georgia argues that the court “explicitly invited Special Master Kelly to make ‘more specific and factual findings and definitive recommendations’” on remand. Further, Georgia argues that after reviewing the “voluminous” record, Kelly “correctly found that Florida’s arguments suffered from a multitude of evidentiary failures that cut across nearly every aspect of the case.”

Digging deeper into the law, Georgia reiterates that to obtain equitable apportionment, “Florida must prove two things: (1) it has suffered serious injury caused by Georgia’s consumptive use, and (2) the benefits of the apportionment outweigh the harm that might result.” Georgia argues that Florida failed to make those showings by clear and convincing evidence — or even by the lower preponderance-of-evidence standard. Further, Georgia suggests that Kelly did not reverse either Lancaster or the court’s conclusions, but rather “reached manifestly correct conclusions supported by the extensive record.” Georgia says that Lancaster had made suggestions but “stopped short of making actual findings” on key issues.

On the questions of harm and causation, Georgia argues that the collapse of the Apalachicola Bay oyster industry in 2012 was due to extreme natural drought and Florida’s mismanagement, not Georgia’s water use. Georgia emphasizes that Lancaster “acknowledged that the 2012 oyster collapse constituted ‘real harm’” but “did not make any findings on whether Georgia’s water use caused the collapse.” Kelly did not “improperly dismiss” government experts, Georgia says, but instead found their evidence was “not persuasive.”

Georgia then emphasizes that after reviewing the evidence, Kelly “correctly found” that its water use is “reasonable,” especially “relative to its population share and economic output, including the economic value of agriculture in the area.” Further, Georgia argues that its recent conservation efforts are extensive and its permit system has been overhauled.

Georgia states that a decree is not warranted because “the benefits to Florida are small and speculative,” while the “costs to Georgia … are certain and severe.” Florida must prove its case “by clear and convincing evidence,” including the balancing inquiry, Georgia reasons, but it failed to do so. Georgia claims its water use is less than that predicted by Florida’s experts, and argues that any cap “would result in only rare and unpredictable increases of Apalachicola flows during drought because of Corps operations.” Finally, Georgia asserts that its costs in complying with a decree would be “massive.”

Amicus brief from the federal government

In addition to the filings from the parties, the acting U.S. solicitor general filed an amicus brief supporting Georgia on two points. The government’s filing addresses two questions:

-

-

- Whether Kelly erred “in concluding that the Corps would not allow the additional water generated by a decree to pass through to Florida when needed and would apply its Master Manual without modification.”

- Whether Kelly erred “in declining to allow additional evidence, as to circumstances after the 2016 trial, concerning reasonable modifications that could be made to the Corps’ Master Manual to accommodate a decree.”

-

The government answers both questions in the negative. Because Kelly determined that capping Georgia’s water use would not benefit Florida, the brief argues, “there was no need for the Special Master to consider the extent to which the Corps could reasonably modify its operations in the Basin” and no need to figure out whether the manual could be “reasonably modified.”

Other amicus briefs

In addition to the federal government, several other entities filed amicus briefs. The Franklin County Seafood Workers Association presents evidence of the impact of Georgia’s water use to Florida oyster fisheries and to seafood workers in Franklin County, a small county in Florida’s panhandle that sits on the gulf of Mexico. The National Audubon Society, Defenders of Wildlife, Florida Wildlife Federation and Apalachicola Riverkeeper asked the court to rely on an amicus brief submitted in 2016; they argue that the “ecological injuries and values at stake” for the Apalachicola Basin could and should be considered, and that the court should use its discretionary authority to recognize ecological values and harm to the environment resulting from Georgia’s water consumption as a matter of law. The Atlanta Regional Commission, supported by a number of Georgia counties, focuses on the Atlanta metropolitan region’s dependence on water from this river system, arguing that Florida abandoned any challenge to metro Atlanta’s water use, which the commission maintains is reasonable.