Argument preview: Is there a substantial chance the justices will affirm the Federal Circuit’s reading of “substantial”?

on Nov 29, 2016 at 7:50 pm

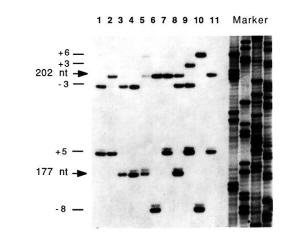

A figure from the patent involved in the case.

Though Life Technologies v. Promega arises out of patent infringement litigation, the issue at the Supreme Court is really a classic statutory interpretation dispute turning on the meaning of the word “substantial.” Because the concept of substantiality is so ubiquitous in law (from the “substantial factor test” in tort causation to the “substantial evidence” test in administrative law), this seemingly narrow patent case should be of interest as much to general appellate practitioners as to patent law specialists.

The statute at issue is Section 271(f)(1) of the Patent Act, which makes it an act of infringement for a person to supply from the United States “all or a substantial portion of the components of a patented invention” so as to actively induce a combination of components overseas that would infringe the patent if that combination occurred in this country. The statute was enacted in response to Deepsouth Packing Co. v. Laitram Corp., a 1972 case in which the Supreme Court held that making or selling a patented invention for export was not infringement provided that some additional assembly remained to be done when the exported shipment left U.S. territory. Many in Congress viewed Deepsouth as creating a “loophole” in patent infringement liability, and Section 271(f) was enacted in 1984 to close that loophole.

Everyone agrees that the statute creates infringement liability where a U.S. company exports all of an invention’s components with “some assembly required” (the exact facts in Deepsouth). But what if someone exports only a few or even just one of the components of a patent invention? The statutory liability extends to supplying “a substantial portion of the components,” but how much is that?

The invention at issue in this case is a DNA testing kit, and the accused infringers in the case exported only one of the components of the kit. The kit, however, has just five components (or at least the parties have assumed that it has just five components – more on that point later). The component supplied from the U.S., a complex catalytic enzyme known as “Taq polymerase,” is essential to the operation of the testing kit. Is one in five – or 20 percent – “a substantial portion of the components” if one component is sufficiently important to the operation of the invention?

To answer that question, the parties are marshalling arguments about three major issues: the correct parsing of the word “substantial” and its immediately surrounding statutory text; the implications of the overall statutory structure of Section 271; and the relevance of the canon of statutory construction against extraterritorial application of U.S. law. The respondent, the patent holder Promega Corporation, has good arguments on the first and second points, but the structural arguments might very well carry the day for the petitioners, Life Technologies Corporation and two other companies accused of infringing Promega’s patent. Let’s examine these arguments in turn.

If the justices focus just on the word “substantial” and its immediately surrounding statutory text, Promega might have the better of the fight. Even the federal government, which filed a “friend of the court” brief in support of Life Technologies, concedes that “[u]ndoubtedly there are many contexts in which a single important component could reasonably be described as a ‘substantial portion’ of a larger whole.” That seems like a wise concession given that the word “substantial” is used in many legal contexts, and its typical meaning would include 20 percent or even 10 percent of a whole. To take just one example, the “substantial factor” test in tort causation clearly embraces situations in which an actor’s negligence is only 10 percent or 20 percent responsible for causing an accident.

Nevertheless, both the government and the Life Technologies contend that the language immediately surrounding the word “substantial” signals a special meaning here. These arguments seem a bit strained. For example, the government maintains that Promega would have a better case if the statute said all or a substantial portion “of a patented invention” rather than “of the components of a patented invention.” The addition of the words “of the components” indicates a congressional intent to focus on numerosity, the government argues, and thus to exclude situations in which a person supplies only a single component. Presumably, the government’s argument means that supplying one in three (33 percent) or even one in two (50 percent) of the components of an invention could never trigger the statute.

Even for a close reader of statutory language, the government’s parsing of the statute seems too clever by half. Among the problems with such a reading is that it suggests a quite different approach when two in ten components are supplied as compared to a situation involving one in five components. Such an approach would elevate in importance how one counts “components” in an invention, and there’s no standard way to do that.

This case provides a good example. The parties have litigated the case assuming that the invention has five components, but that assumption is not obviously correct. The relevant patent divides the invention into five of what patent attorneys would call patent claim “elements,” but each of those five elements includes at least two components: a “vessel” and a substance inside the vessel. It is true that the substance inside the vessel has greater importance, from a technological standpoint, than the vessel. Yet the “vessel” itself is undeniably required by the patent claim and thus undeniably a part of the patented invention. This very case could therefore be viewed as involving the supply of not one in five components, but perhaps two in ten. (The record is not clear on whether the vessel is supplied from the United States.) Should that way of counting components make a big difference in the legal framework applicable to the case? I certainly hope not, for if it does, then future litigants can expect many pointless disputes about how to count “components” of an invention.

The larger statutory structure supplies Life Technologies and the government with much better arguments. Section 271(f) includes two paragraphs; the second paragraph imposes infringement liability when a party supplies a single component if and only if that component is “especially made or especially adapted for use in the invention and not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use.” That second paragraph seems to indicate a congressional judgment not to impose liability merely for selling a “staple article” of commerce. As it happens, the single component (or pair of components) supplied in this very case – Taq polymerase (or a vessel with Taq polymerase in it) – is a staple article of commerce. Although you can’t pick up Taq polymerase at your local supermarket or department store, you can buy it on Amazon.com (for the low price of $29.50 per 1000 units!), and it has substantial noninfringing uses.

That structural argument persuades me that something is amiss with the analysis of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which permitted liability against the defendants even though they are supplying merely a staple article in this field. The statutory structure suggests that no infringement liability should arise in such circumstances, without regard to whether the staple article counts as one component or two components.

I should note that there are counterarguments to Life Technologies’ structural argument. As Promega notes, Section 271(f)(1) requires that the supplier “actively induce” the overseas combination, and that requirement has been interpreted to include a high level of intent to infringe on the part of the defendant. I’m not sure this point is entirely convincing, but I hope that the justices expend most of their time on such competing structural arguments, which seem to be the real heart of the statutory issue.

The third and final issue concerns the canon against extraterritorial application of U.S. statutes. That canon played an important role in the Supreme Court’s 1972 Deepsouth decision, which appropriately stated that “[o]ur patent system makes no claim to extraterritorial effect.” But Congress clearly intended to overrule Deepsouth and to extend patent infringement liability to the supplying for export of “a substantial portion of the components of a patented invention.” If that phrase, fairly interpreted, would extend to supplying one in five, or 20 percent, of the parts of an invention, the Court should not put a thumb on the scale against that reading (for example, by raising the required portion to 30, 40 or 50 percent) merely to decrease the effect of a law that Congress clearly wanted to have some extraterritorial effect. Such a move would seem to have less to do with statutory construction than with a judicial bias against statutes that have extraterritorial effects.

Let me now answer the question posed at the beginning of this argument preview: Is there a substantial chance the justices will affirm the Federal Circuit’s reading of “substantial”? In its past three terms, the Supreme Court has granted certiorari in ten Federal Circuit patent cases and affirmed in only two, or 20 percent, of them. Once the Supreme Court grants certiorari, the smart money should always bet on a reversal of a Federal Circuit patent decision. Yet based on the data, I have to say that there’s a substantial chance of affirmance, but that’s just because I believe that 20 percent, or a one in five chance, is “substantial.”