Argument preview: Is a three-judge court “not required” when a pleading fails to state a claim?

on Oct 19, 2015 at 1:14 pm

Congress created the three-judge district court in 1910; the procedure directly responded to the Supreme Court’s decision in Ex Parte Young, which allowed a federal district court, presided over by a single judge, to enjoin enforcement of an unconstitutional state law. By moving such cases to three-judge district courts, Congress sought to achieve several things: to limit the power of a single district judge to enjoin enforcement of state (and later federal) laws; to make it more difficult for plaintiffs to obtain such injunctions; to ensure that any injunction is more authoritative, better reasoned, and more likely correct because multiple judges, many from outside the local area, were involved in the deliberation and decision; and to ensure that such injunctions receive expeditious and final Supreme Court review.

In Shapiro v. McManus, to be argued on Wednesday, November 4, the Court will consider the proper distribution of power in cases potentially governed by the three-judge procedure. Specifically, the Court must decide whether a single district judge can dismiss a complaint for failure to state a claim under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) without referring the case for three-judge consideration.

As amended in 1976 and codified at 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a), challenges to the constitutionality of apportionment of congressional and state legislative districts are resolved by three-judge district courts. Congress also may provide that cases under particular federal legislation must be heard by three-judge courts; examples include the Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act of 2002, the Communications Decency Act of 1997, and the Voting Rights Act. Judgments of three-judge district courts are immediately and mandatorily reviewable by the Supreme Court, without having to pass through the courts of appeals.

Prior to 1976, three-judge courts heard all actions seeking to enjoin enforcement of state and federal laws as unconstitutional. The amendments were designed to limit the frequency of three-judge proceedings and the docket pressures they had imposed on both district courts and on the Supreme Court — by the early 1970s, more than 300 three-judge courts were being convened annually — while retaining the procedure for legislative apportionment and in cases in which Congress specifically deemed it appropriate. The cases still subject to three-judge resolution are unified by a unique need for authoritative lower-court decisions and quick final review, either because they involve voting-rights issues that should be resolved prior to a looming election or because they involve questions of the constitutionality of legislation that Congress deemed sufficiently important.

Section 2284(b) dictates how a three-judge court is convened and functions, including the division of authority between the single judge and the three judges. A case is assigned to a single district judge pursuant to local rules and any party (usually the plaintiff) can request a three-judge court. The assigned judge notifies the chief judge of the circuit of the request; the chief judge appoints two additional judges, one of whom must be from the court of appeals, creating a panel comprised of the original assigned district judge, one circuit judge, and a third judge, who may come either from the circuit or from the district.

Importantly, however, the single district judge must refer the case for a three-judge court “unless he determines that three judges are not required.” This flipped the pre-1976 language, which required the single judge to notify the chief circuit judge whenever a three-judge court was “required.” Once the district court has determined that a three-judge panel is required and the panel is convened, Section 2284(b)(3) dictates the division of authority between the single judge and the three-judge court. The single judge can grant a temporary restraining order, conduct all pre-trial proceedings, and enter all orders allowed under the Federal Rules. But she cannot decide on preliminary or permanent injunctions or enter judgment on the merits; those decisions must be made by the full panel. In addition, the three judges can review any decision of the single judge prior to final judgment.

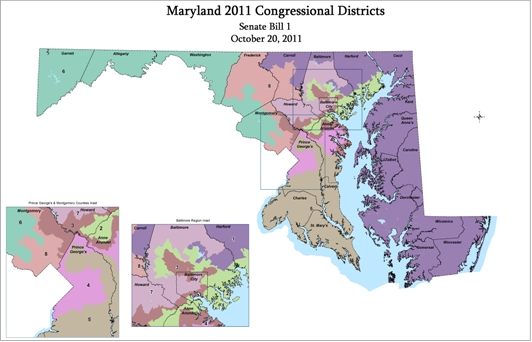

This case is a pro se challenge to Maryland’s redistricting plan; a group of voters allege that the state engaged in partisan gerrymandering in violation of the First Amendment and whatever remains of the jurisprudence over partisan gerrymandering after 2004’s Vieth v. Jubelirer. The single district judge refused to refer the case, applying Fourth Circuit precedent permitting a single judge to dismiss a legally insufficient complaint without referring the case for three-judge consideration. The single district judge did just that, concluding that the First Amendment arguments lacked merit. Because the single judge made the final decision, the appeal in the case ran to the Fourth Circuit rather than to the Supreme Court; the court of appeals summarily affirmed.

The voters argue that the text, structure, and purpose of Section 2284 prohibit a single judge from refusing to refer a case for a three-judge court by deciding that a pleading fails to state a claim.

Their starting point is what Section 2284(b)(1) means in allowing a single judge to determine that a three-judge court is not required. It obviously is not required when Section 2284(a) is not satisfied because the lawsuit does not challenge the constitutionality of apportionment or because another federal statute does not require a three-judge court. But, the voters accept, “like most things, it’s not quite that simple.” In some pre-1976 cases, the Court held that an action need not be referred if the court lacks federal subject-matter jurisdiction. This included cases in which the claim was constitutionally insubstantial, meaning wholly insubstantial or obviously and essentially frivolous. The challengers argue that the 1976 amendments must be read against that precedent and understood as incorporating it. Thus, a single judge can dismiss a claim as insubstantial or frivolous because such a claim does not fall within the court’s jurisdiction.

But, they argue, the Fourth Circuit’s jurisprudence erroneously equates insubstantiality not with frivolousness, but with failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6). A claim is not wholly insubstantial or frivolous merely because it fails to state a claim for relief; a claim can be non-frivolous but still be dismissed because of questionable merit. Moreover, by treating such insubstantial claims as outside the court’s jurisdiction, the insubstantiality doctrine works an exception to the general rule that failure to state a claim calls for a judgment on the merits and not dismissal for want of jurisdiction. Thus, a single-judge dismissal for failure to state a claim, in which that claim is not wholly insubstantial, is not the type of jurisdictional dismissal permitted by the Court’s pre-1976 jurisprudence that was incorporated into the amended statute. Rather, it violates Section 2284(b)(3)’s restriction on the single judge entering judgment on the merits.

The voters also insist that the Fourth Circuit’s rule is inconsistent with the general purposes of the three-judge process. It allows the single judge to render a decision on the substantive legal merits of a constitutional claim, rather than preserving that for the multiple minds of the three-judge court. It also adds multiple layers of litigation, slowing what is intended to be an expeditious process. Because a three-judge panel did not make the decision to dismiss for failure to state a claim, it is not directly appealable to the Supreme Court. It instead must be appealed to the court of appeals (as happened here) before seeking certiorari – a process that could add more than two years to the litigation. And if the Court ultimately reverses the dismissal, the case returns to the district court to start all over again for a decision by the three-judge court on the actual merits (as opposed to jurisdiction), which can then be directly appealed back to the Court. Under Fourth Circuit’s approach, the Court would not have had jurisdiction over last Term’s Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, or this Term’s Evenwel v. Abbott, both of which review dismissals by three-judge courts. On the other hand, if the single judge denies the Rule 12(b)(6) motion and refers the case, the defendant’s first move almost certainly will be to re-litigate that same motion, now seeking a judgment on the merits, before the three-judge court.

Judicial Watch, Common Cause, two law professors, and the NAACP filed separate amicus briefs in support of the challengers. All emphasized the special role of the three-judge court in voting-rights cases and the problem caused by delays in such cases from a single judge’s improper dismissal under Rule 12(b)(6). The NAACP ties its position specifically to Shelby County v. Holder; it argues that the elimination of pre-clearance under the Voting Rights Act places greater weight on post-enactment litigation to challenge discriminatory state voting laws, which requires a three-judge court and the efficiencies and benefits of the three-judge district court. The Fourth Circuit’s approach undermines those efficiencies.

The state officials offer a different view of Section 2284’s text and the purposes of three-judge courts, both of which vindicate the Fourth Circuit’s approach. They insist that nothing in the text precludes the single district judge from dismissing for failure to state a claim. Section 2284(b)(1) empowers the single judge to determine that three judges are not required, but it does not prescribe or limit the reasons the judge might reach that conclusion. Notably, Congress did not expressly incorporate the insubstantiality or frivolousness standard into the 1976 amendments, although it certainly knew how to include that language in a procedural statute. Nor is the single judge’s power to not refer limited to cases in which jurisdiction is lacking. Section 2284 is a non-jurisdictional statute; it establishes a procedural mechanism that is triggered only upon request by a party, not at the time of filing the complaint, and that can be waived if the parties do not request a three-judge panel. Thus, Section 2284(a)’s mandatory language — that a three-judge court “shall be convened” — is not absolute and is subject to judge-made exceptions.

Moreover, Section 2284(b)(3), which prohibits the single judge from entering judgment on the merits, does not affect the analysis. The division of authority between the single judge and the three-judge panel applies only after a three-judge panel has been convened. But this case concerns the prior question of whether a three-judge court is required in the first instance, a decision vested, without limitation, in the single judge under Section 2284(b)(1).

Because the text does not preclude a single judge from dismissing for failure to state a claim prior to referring the case for a three-judge court, the question becomes whether such a dismissal is consistent with Section 2284’s purpose. The state officials argue that the sole purpose of the three-judge procedure (as amended in the 1976 statute) is protecting states from having their hands tied by a single federal judge’s imprudent or hasty constitutional decision invalidating the state’s apportionment decisions. Cases must be resolved in the fastest, most efficient way possible; any procedure that gets states out of such constitutional litigation in a speedy or expeditious fashion is consistent with that purpose. The Fourth Circuit’s approach, they argue, does just that. It allows for quick resolution of a meritless constitutional challenge without imposing on the court and the state the burden, time, expense, or inconvenience of invoking the extraordinary and cumbersome procedure of the three-judge court. There is no reason, consistent with the statutory purpose, to require three judges to decide that a claim is plainly legally insufficient, a determination that single district judges regularly make. By allowing for such early termination, states are relieved of the burden of long or overly complicated constitutional litigation, consistent with the goals of the three-judge process.