Argument analysis: Justices seem divided about government right to challenge patents in administrative process

on Feb 19, 2019 at 4:02 pm

The justices have a light calendar this week, with only two arguments. If the first argument of the week (Return Mail Inc. v. U.S. Postal Service) is any guide, they’ve spent their extra time focusing carefully on the relatively thin session. At first glance, Return Mail is a simple statutory case, involving another in a long line of drafting flaws in the AIA (Congress’ 2011 patent-reform bill, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act). But the argument presented a highly engaged bench, with all of the justices (except Justice Clarence Thomas) asking pointed questions, several of which seemed to raise the stakes higher than we might expect for a simple patent case.

The case involves a series of provisions in the AIA that establish procedures for “post-grant review” of patents. Those procedures permit any “person” to ask the Patent and Trademark Office to review previously issued patents and invalidate them if the PTO decides that it made a mistake when it issued the patent initially. In this case, for example, the U.S. Postal Service asked the PTO to reconsider a patent previously issued to petitioner Return Mail for an invention involving the use of bar codes in facilitating the processing of undeliverable mail. The question for the justices is whether the Postal Service (or other agencies of the federal government) is a “person” entitled to use those procedures. The Dictionary Act establishes a presumption that “person” is limited to private entities; the question in this case is whether there is any adequate reason to override that presumption.

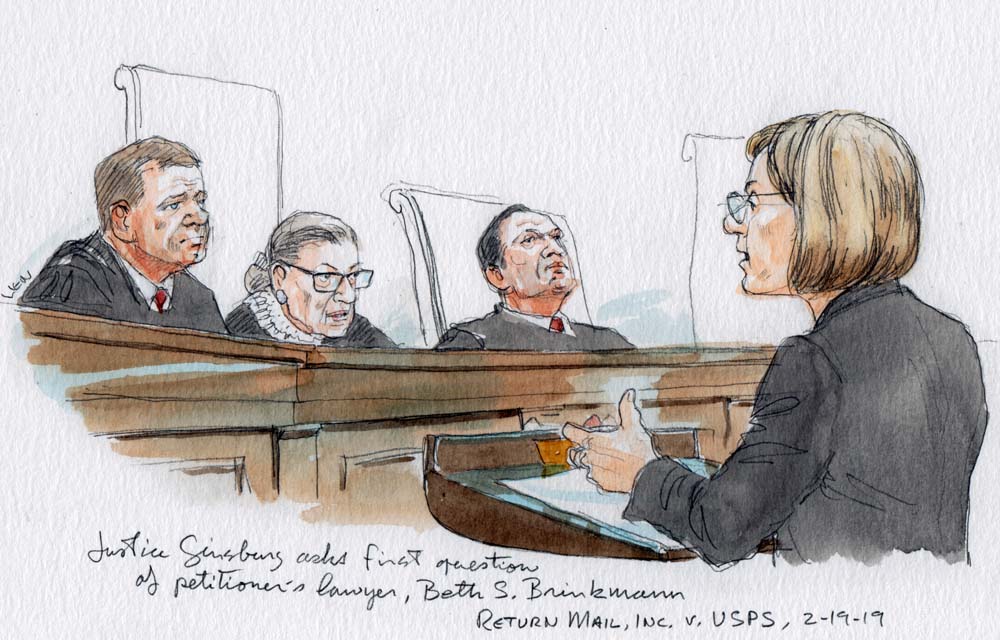

The relentless questioning during the presentation of Beth Brinkmann, representing Return Mail, would have suggested that Return Mail had little chance of prevailing. One line of inquiry, pursued by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer, asked why Congress possibly could have intended to exclude the government from the benefits of post-grant review. Recognizing that the premise of the statute is that the administrative process provides a path cheaper than litigation for businesses to eliminate weak patents asserted against them, Ginsburg asked, for example, “[W]hy would Congress want to leave a government agency out of this second look if the idea is to weed out patents that never should have been given in the first place?” Similarly, Sotomayor asked, if “this is a defense tool for [alleged] infringers, [d]oes it make logical sense to deprive the government of the tool of being able to invoke this proceeding?” Even more pointedly, Breyer asked, “[W]hy would Congress not want to allow that agency to use this fairly efficient method to get rid of what they see as an invalid patent that blocks their way?”

Another group of justices seemed troubled by the implications of Brinkmann’s reading of the statute as applied to a process called “ex parte reexamination,” by which any “person” can ask the PTO to initiate administrative review. The problem started when Sotomayor asked Brinkmann how the Post Office would go about instituting ex parte re-examination if it is not a “person” entitled to send the communication that starts that process. Brinkmann responded by explaining that the affected agency should contact the director of the PTO directly and ask the director to institute the review. Her response struck several of the justices as unseemly.

Apparently incredulous, Justice Samuel Alito asked, “[D]o you think it would be proper for the Postal Service or some other federal agency to contact the PTO ex parte and say, ‘Hey, why don’t you sua sponte look into the validity of this patent?’ Is that what you’re saying? That would be proper?” When Brinkmann confirmed her position, Alito responded:

[T]hat’s an argument that makes me doubt your argument on the statutory language because I think if this were presented to Congress and the issue before Congress was do we want a federal agency to initiate one of these AIA proceedings in the open, in accordance with the law, or do we want to allow them to pick up the phone to the PTO … Do you think they chose the latter?

Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch voiced similar concerns.

As Brinkmann finished her presentation, the key problem for her side of the case seemed to be the absence of any strong reason why Congress would have wanted to exclude government agencies from the benefits of post-grant review. But Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart, representing the Postal Service, could barely start his argument before he faced a torrent of inquiries from three justices who seemed to have a well-attuned notion of why Congress would want to exclude the government. Surprisingly, first on the attack was Sotomayor. Referring to an amicus brief from the Cato Institute, she suggested a foundational problem with allowing the government to participate in administrative post-grant review proceedings:

The deck is stacked against a private citizen who is dragged into these proceedings. They’ve got an executive agency acting as judge with an executive director who can pick the judges, who can substitute judges, can reexamine what those judges say, and change the ruling, and you’ve got another government agency being the prosecutor at the same time. In those situations, shouldn’t you have a clear and express rule?

Gorsuch – not always Sotomayor’s intellectual soulmate – had a similar reaction. Imagining a case in which the PTO might resolve a post-grant review proceeding against the federal agency, he envisioned a “scenario” in which “the government speaks out of both sides of its mouth.” For him, “coming to Court for us to resolve that dispute about the executive department’s view of the law, that’s unusual. Not to say unprecedented, but unusual. And shouldn’t we, as Justice Sotomayor suggested, at least expect some sort of clarity from Congress when it wants that unusual arrangement to reign?”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh seemed the most settled in his aversion to the government’s routine participation as a challenger in post-grant review proceedings. Unlike Alito, he saw nothing troubling about informal communications between one agency and the PTO: “[W]hy is that [problematic]? Under Article II, I would think all components of the executive branch always are able to communicate with one another absent some rule to the contrary that Congress might try to insert.” So Brinkmann’s approach didn’t seem to bother him in the slightest. He was, though, unsettled by the hypothetical Gorsuch had posited, presenting “agency versus agency in federal court.” For him, because that arrangement was “not unprecedented, but unusual,” the statute’s failure to address the question seemed dispositive: “When you take a step back here and think about this case, there are provisions that specifically give the government the same rights as persons. … We don’t have them here, obviously.” For him, that suggested, “as Justice Sotomayor says,” that the justices should rely on “the presumption that the government is not a person.”

The most reflective passages of the argument came late in Stewart’s presentation when Alito suggested that the entire discussion was “indulg[ing] the possible fiction that Congress actually gave a second of thought to the issue that’s before us.” A few minutes later, Justice Elena Kagan picked up that reference with a rhetorical question: “[G]o[ing] back to Justice Alito’s question – does anybody really think Congress thinks about this as a default rule and legislates against it? And if not, shouldn’t we just do what strikes us as the thing Congress would have wanted done with respect to any particular statute?”

The schizophrenically heated argument suggests that it is not at all easy to predict how the justices will resolve this one. One clue may lie in Stewart’s answer to a question from Kavanaugh about the “real world problems for the government” that might flow from an adverse decision. When Stewart responded that federal agencies combined have submitted only 20 requests for post-grant review since enactment of the AIA, he almost seemed to concede that a ruling in favor of the government might create more trouble than it would be worth. At least for the justices who take seriously the problems fleshed out in their questioning of Stewart, a vote for Return Mail seems a simple way to force Congress to refine the statute in a way that delineates the government’s role with more care.

Editor’s Note: Analysis based on transcript of oral argument.