Empirical SCOTUS: What to expect from Kavanaugh’s first term

on Oct 10, 2018 at 1:44 pm

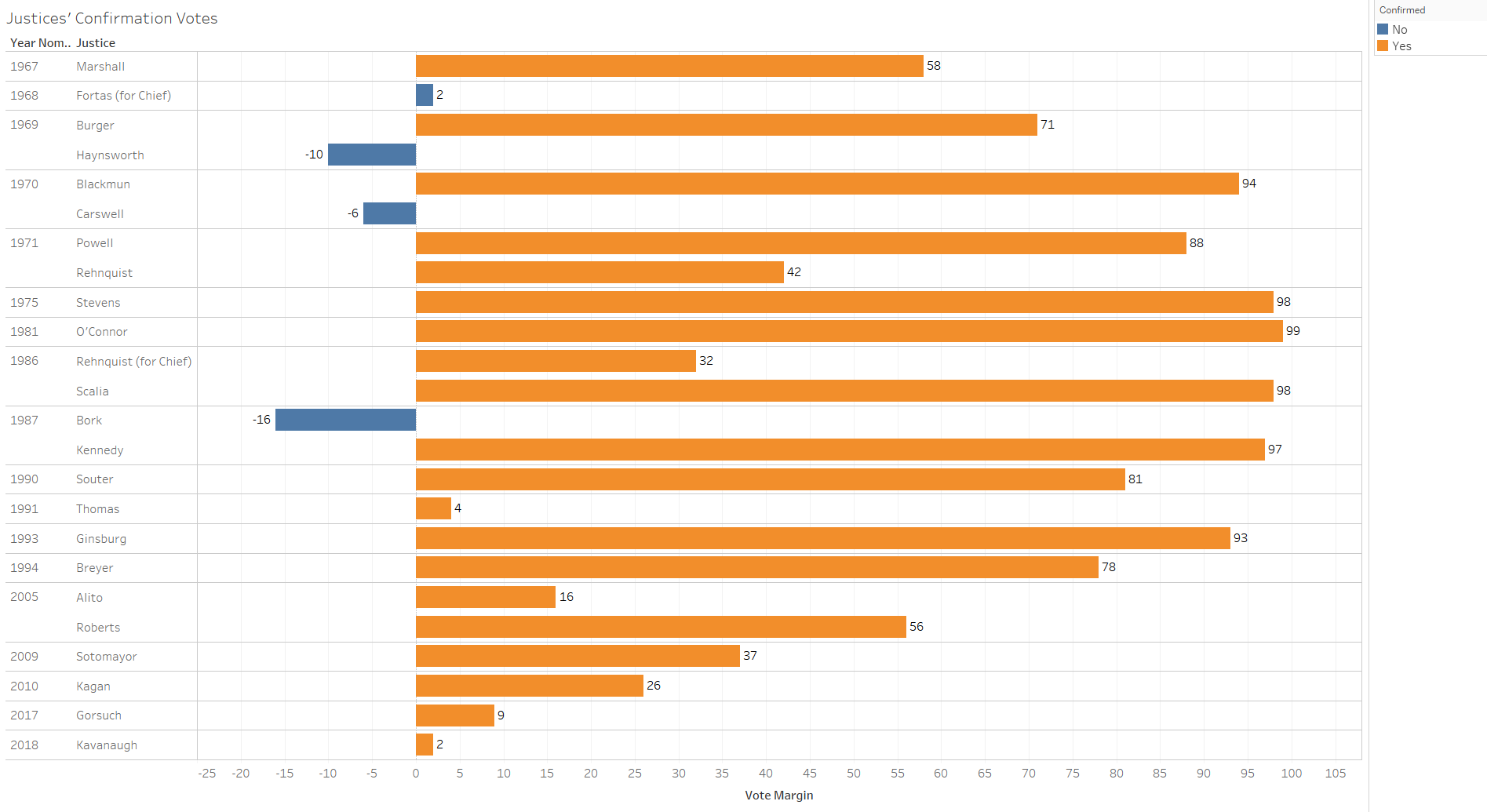

The tense waiting is now over as Justice Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to the Supreme Court on October 6, 2018. One of the big stories about Kavanaugh has been his low rate of public approval. This low rate of approval was apparent soon after Kavanaugh was nominated. Not only this, but as the figure below shows, Kavanaugh was confirmed by the smallest vote margin of any sitting justice (He was actually confirmed by the smallest margin of any successful justice outside of Justice Stanley Matthews in 1881, who was confirmed by a single-vote margin.).

This leads to an interesting question – whether this low rate of approval both from the public and from the Senate will affect Kavanaugh in his early career on the court. Although each justice has his or her own particular reactions to such things, indications can be gleaned from the different justices’ experiences. Justice Clarence Thomas, for instance, has been silent for the vast majority of oral arguments in which he participated. Could this have had to do with his confirmation process and the subsequent fallout? Should we then expect the same from Kavanaugh?

Kavanaugh’s first oral arguments

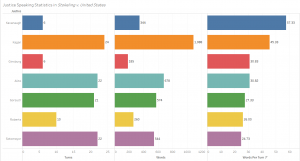

After one day of oral arguments, Kavanaugh has been more participatory than Thomas was in his first days working on the Supreme Court. During his first argument in Stokeling v. U.S., Kavanaugh fell in the middle of the justices for words spoken but actually said more per each talking turn than any of his colleagues.

The justices also heard argument yesterday in U.S. v. Stitt. When looking at Kavanaugh’s first-day speaking statistics as compared to the those of his fellow justices, he was on the low end for average words spoken (Thomas did not speak on his first day), but had more average words per turn than all justices except Justice Stephen Breyer.

A Kennedy court no longer

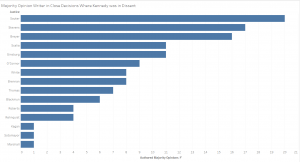

The last time the Supreme Court was without Kennedy was over 30 years ago, in the October 1986 term. During Kennedy’s tenure on the court, he was often described as the court’s most powerful justice. Kennedy also sat out very few cases while on the court. The following figure shows the number of decisions each justice participated in without Kennedy while Kennedy was a member of the court and the number of times the justices dissented in those decisions.

Justice John Paul Stevens voted in the most decisions in instances when Kennedy sat out. Although little else can be extracted from these data, Justice Antonin Scalia dissented more than any other justice.

Another way to gauge how things might change with Kennedy now retired from the court is through reviewing decisions in which other justices aside from Kennedy were in the swing-justice position. The following figure looks at cases decided by a single vote when Kennedy was in dissent.

Stevens and Scalia participated in the most of these cases, with Stevens in the majority in many more instances than Scalia. This figure helps clarify that close decisions when Kennedy was in dissent often moved in the liberal direction. The justices most frequently in the majority in these decisions were more liberal justices, including Justices William Brennan, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and David Souter, along with Stevens, Justices Thurgood Marshall and Sonia Sotomayor, and others. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was least frequently in the majority in such decisions.

The story is much the same with majority authors of such close decisions with Kennedy in dissent.

The top three justices with the most such majority opinions, Souter, Stevens and Breyer, were also from the court’s more liberal bloc. The main takeaway from these last two figures is that the court’s liberals were often in the majority in close cases when Kennedy was in dissent. With a potentially much more conservative justice in Kavanaugh filling Kennedy’s seat, we should not expect similar outcomes. Kavanaugh will likely disagree with his conservative colleagues less frequently than Kennedy did and will likely support a conservative majority in many of the court’s decisions that come down to one vote.

What we can learn from the other justices’ behavior

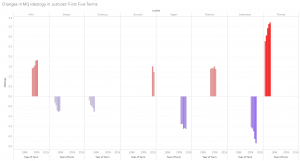

Even if Kavanaugh is a relatively conservative justice, this may not necessarily become apparent in his early career on the Supreme Court. If it does, we still may not know the extent of his liberalism or conservatism for many years to come. All of the justices aside from Chief Justice Roberts (for Justice Neil Gorsuch it is too soon to tell) were more moderate when they started on the Supreme Court compared with a few years down the line (This figure is based on the justices’ Martin and Quinn ideology scores.).

This trend basically holds true when looking at the justices’ voting behavior as either liberal or conservative and comparing their first 50 votes with their career track records on the Supreme Court.

Roberts, Justice Samuel Alito and Sotomayor show little change from their first 50 votes; much more change is evident from Breyer, Ginsburg, Justice Elena Kagan and Thomas.

First term legitimacy and confirmation votes

Looking back at the first figure, Ginsburg and Breyer were confirmed by the greatest margin of votes, while Thomas and Gorsuch had the fewest supporting votes of the sitting justices aside from Kavanaugh. Could a smaller voting margin portend less legitimacy among one’s peers on the Supreme Court? Might it cause a justice to feel greater frustration with the confirmation process? There are a few means to probe for answers to these questions.

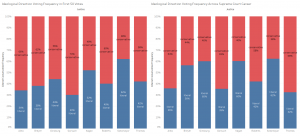

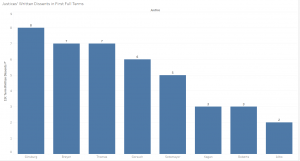

In terms of legitimacy, one possibility is that fewer justices vote alongside justices who were confirmed by smaller margins, especially early in the newer justices’ Supreme Court careers. The following figure looks at the average size of the court’s majority across when a justice authored an opinion in his or her first full term (For the purpose of this post, Thomas’ first term was 1991 even though he didn’t assume office until October 23, after the term had begun.).

This metric likely measures the relative fracturing nature of the decisions assigned to a justice as much as or more than it does the other justices’ views of the recently confirmed justice. This is apparent as Thomas’ majorities are toward the high end for majority-coalition size, while Gorsuch had the lowest average majority-coalition size, followed by Ginsburg. Gorsuch had more 5-4 decisions last term (his first full term) than any of the other justices on the court, while Thomas is known for being assigned relatively noncontentious decisions.

Frustration with the confirmation process might be measured in the form of written dissents, although dissents may also bear a strong relationship to case selection.

As we see, Ginsburg, Breyer and Thomas dissented the most in their first full terms, followed by Gorsuch. Because Ginsburg and Breyer were both confirmed by large majorities, the relationship between written dissents and confirmation-vote margin is not robust.

A third potential measure of legitimacy might be traced to the justices’ frequencies in the court’s majorities during their first full terms.

Only four justices were in the court’s majority less than 90 percent of the time in their first terms – Kagan, Sotomayor, Gorsuch and Thomas. Ginsburg was in the majority the greatest percentage of the time of all of the sitting justices. This measure holds some promise in terms of its relationship to the margin of a justice’s confirmation vote, and we’ll have to wait and see whether Kavanaugh falls to the lower end of this metric relative to his colleagues.

Relationship to colleagues

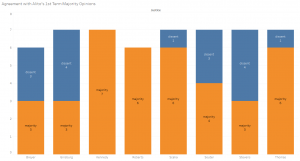

One thing we very well might learn about Kavanaugh in his first term is which justice coalitions he is likely to join. The justices tend to give a sense of this in their first terms, some more than others.

During Alito’s first full term, for instance, the more liberal justices were much more frequent dissenters from his majority opinions than were the conservative justices.

The same held true for Gorsuch — and it was even more pronounced because Gorsuch authored majority opinions in many tightly decided cases.

Ginsburg’s majority coalitions tended to be built with the liberal justices even in her first term on the court.

If expectations hold true to form, we should see more agreement from conservative justices when Kavanaugh authors majority opinions this term, although surprises are always possible.

All of this amounts to a few likelihoods and many uncertainties. We should expect Kavanaugh to vote more moderately this term than he does in future terms. Because he is already vocal at oral argument, he should continue to be so. The more conservative justices will likely vote alongside Kavanaugh and Kavanaugh’s behavior along with the cases he is assigned will likely dictate the level of support he gets from his liberal colleagues. Very little apparent fallout should be expected from the confirmation process. Kavanaugh said as much when he took the oath for the second time. The more latent effects from the confirmation process will be less apparent. Maybe there will be a lasting consequence in Kavanaugh’s behavior or in his relationships with the other justices, although neither will likely become immediately evident. Although much about Kavanaugh’s behavior as a justice on the Supreme Court will take years to process, we should start seeing inklings of his judicial behavior early this term — as we already did during his first day of oral arguments.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.