Justice Kennedy: He swung left on the death penalty but declined to swing for the fences

on Jul 2, 2018 at 11:27 am

Carol S. Steiker is the Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law and Faculty Co-Director of the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School. Jordan M. Steiker is the Judge Robert M Parker Endowed Chair in Law and Director of the Capital Punishment Center at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

As in many other areas of the law, Justice Anthony Kennedy often provided the key fifth vote in death penalty cases during his three decades on the Supreme Court. Swinging to the right, Kennedy was a frequent supporter of restrictions on the availability of federal habeas review of capital cases, a skeptic of claims challenging the constitutionality of lethal injection and a relatively reliable vote against granting stays of execution in end-stage capital litigation. Kennedy will likely be remembered more, however, for his swings to the left, because he was the author of numerous opinions that broke new ground in the court’s Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. Most importantly, he was the primary architect of the court’s proportionality doctrine that led to exemptions from the death penalty for offenders with intellectual disability, juvenile offenders and nonhomicide offenders. He also ultimately joined decisions embracing a broad right of capital defendants to present and have fully considered all relevant mitigating evidence. Finally, he was the first justice to raise concerns about the extensive use of solitary confinement on death row. Overall, he solidified the court’s role in subjecting American death penalty practices to frequent and detailed — though not particularly intrusive — constitutional regulation. Kennedy never joined calls from members of the court (Justices Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg) to reconsider the constitutionality of the death penalty as a punishment, but his jurisprudential glosses on the court’s proportionality doctrine arguably strengthen the case for judicial abolition.

In 1989, at the end of his first full term on the court, Kennedy joined majority opinions rejecting claims that offenders with intellectual disability and juvenile offenders should be categorically exempt from capital punishment under the Eighth Amendment. Many observers thought that these decisions represented the end of the road for proportionality challenges to the scope of the death penalty. But starting in 2003, the court’s proportionality jurisprudence was expanded in a series of five key majority opinions, all of which were joined by Kennedy, and three of which he authored. The first, Atkins v. Virginia, authored by Stevens, overturned one of the 1989 decisions and declared the death penalty unconstitutional for offenders with intellectual disability. Stevens noted that 16 states had outlawed the execution of offenders with intellectual disability between 1989 and 2003 and explained that the “consistency of the direction of change” suggested an emerging consensus against the practice. Stevens also noted in a footnote that there was “additional evidence” of “a much broader social and professional consensus” in the views of expert organizations, representatives of diverse religious communities, the world community and the general public as reflected in polling data — a footnote upon which Justice Antonin Scalia bestowed a sarcastic “Prize for the Court’s Most Feeble Effort to fabricate ‘national consensus.’”

Two years later, Kennedy built on Stevens’ decision in Atkins when he authored the opinion for the court in Roper v. Simmons, overturning the second 1989 decision and declaring the death penalty unconstitutional for juvenile offenders. The number of states rejecting the practice was identical to that in Atkins, and Kennedy doubled down on the “world opinion” aspect of Stevens’ footnote, defending in ringing terms the relevance of international practice to constitutional decision-making: “It does not lessen our fidelity to the Constitution or our pride in its origins to acknowledge that the express affirmation of certain fundamental rights by other nations and peoples simply underscores the centrality of those same rights within our own heritage of freedom.”

In 2008, Kennedy wrote for the court in Kennedy v. Louisiana, applying the Atkins/Simmons framework to reject the death penalty for offenders convicted of raping children. Only a handful of states had authorized death sentences in such cases, so the legislative nose count was quite lopsided against the practice. However, Kennedy wrote the opinion more broadly than the case required in two ways. First, he made clear that the holding was not limited to the crime of child rape but rather extended to all crimes against individual persons short of murder. Second, Kennedy rested the court’s decision in part upon the troubling tensions within the court’s Eighth Amendment jurisprudence that had led Blackmun to call for the constitutional abolition of the death penalty in his dissent from denial of certiorari in Callins v. Collins shortly before his retirement. In Kennedy’s view, the court’s work was “not all together satisfactory” and thus called for “confining the instances in which capital punishment may be imposed.”

The final two proportionality cases broke down the wall separating the Eighth Amendment’s application in capital and noncapital cases. In 2010 in Graham v. Florida, Kennedy wrote for the court holding unconstitutional a sentence of life without parole (LWOP) for juvenile offenders convicted of nonhomicide crimes, applying the proportionality analysis that had been developed in Atkins, Simmons and Kennedy. Two years later in Miller v. Alabama, Justice Elena Kagan extended Kennedy’s analysis in Graham to preclude the mandatory imposition of an LWOP sentence on juvenile offenders convicted of homicide. Kagan built on Kennedy’s reasoning likening the sentence of juvenile LWOP to the death penalty, because it is an unusually severe penalty and the harshest one constitutionally available for juveniles. These juvenile LWOP cases further entrenched and expanded the court’s Eighth Amendment proportionality doctrine and for the first time suggested that it had application beyond the hermetic world of capital litigation.

In addition to crafting a substantial expansion of the court’s proportionality doctrine, Kennedy also provided a key vote to strengthen the pre-existing requirement that defendants be permitted to introduce all relevant mitigating evidence in capital sentencing. When Kennedy arrived in 1988, the court was just beginning to wrestle with the tension between the two most conspicuous pillars of its Eighth Amendment jurisprudence: the commitment to “guiding discretion” in sentencing proceedings to prevent arbitrariness, and the guarantee of “individualized sentencing” to ensure defendants could present (and have considered) all mitigating evidence that might support a sentence less than death. In 1989, the court held in Penry v. Lynaugh that the Texas death penalty statute that it had provisionally approved in 1976 was inadequate to facilitate consideration of a defendant’s evidence of childhood abuse and intellectual disability. Kennedy joined Scalia’s dissent, which argued that an expansive approach to individualized sentencing was inconsistent with the court’s commitment to narrowing discretion in capital cases. The stakes of the case were high because Texas was emerging as the most active executing state in the country, and the decision threatened to reverse scores of death verdicts obtained under the challenged statute. Kennedy wrote a crucial decision a few years later in Johnson v. Texas narrowing the Penry majority’s holding. He reasoned that states need only provide for “some” consideration of a defendant’s mitigating evidence and need not ensure that such evidence is considered in all of its dimensions. That decision allowed Texas to continue its leading role in executions.

In a series of subsequent decisions, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor urged a more robust reading of the individualization requirement, arguing that capital defendants should be afforded “full consideration” of their mitigating evidence. It wasn’t constitutional, in her view, to limit consideration of a defendant’s mitigating evidence to narrow questions concerning whether the defendant acted “deliberately” or whether the defendant would be dangerous in the future. Instead, states are required to provide a vehicle for jurors to consider mitigating evidence as it relates to a defendant’s reduced moral culpability. Kennedy ultimately changed course and provided the crucial fifth vote in two 2007 decisions, Brewer v. Quarterman and Abdul-Kabir v. Quarterman, upholding this broader individualization right. Without Kennedy’s change of heart, the court might well have resolved the tension between guidance and individualized sentencing by jettisoning the individualization requirement entirely.

Although Kennedy did not join others on the court in calling for a reconsideration of the death penalty as a punishment, he took a particular interest in a widespread aspect of its present administration — the housing of death-row inmates in solitary confinement. His interest in this issue was striking because it was not based on inmates challenging such incarceration in litigation before the court. During oral argument in 2015 in Davis v. Ayala, a case concerning race discrimination in jury selection, Kennedy seemingly out of the blue asked counsel about the nature of his client’s death-row confinement, including how long the inmate was allowed outside of his cell. Kennedy ultimately provided the crucial fifth vote to overturn relief for the inmate on the race-discrimination ground, stating that his rejection of the inmate’s claim was “unqualified.” But he wrote separately in Ayala to call attention to the fact that the inmate had spent more than 25 years in solitary confinement on death row. He emphasized specific details of that confinement, including that the inmate’s windowless cell that was no larger than a parking spot and that the inmate had little opportunity for interaction or conversation with anyone. Kennedy highlighted the “human toll” of such confinement, and asserted that despite its cruelty, the practice of solitary confinement had not been subject to adequate public scrutiny. He closed by quoting Dostoyevsky, who famously observed that “the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.”

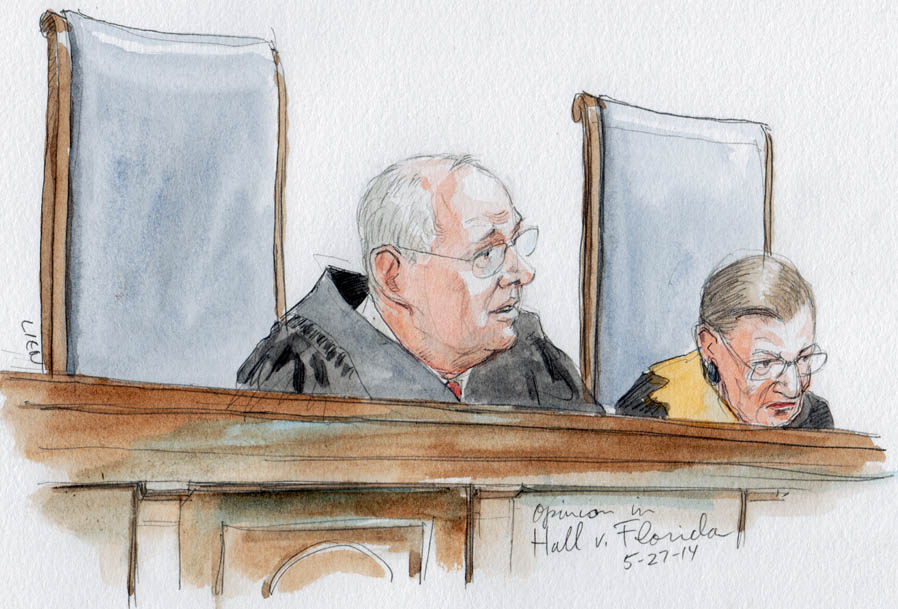

Kennedy’s concern about the cruelty of solitary confinement provides some support for Breyer’s global attack on the death penalty, particularly Breyer’s insistence in his dissent in Glossip v. Gross that the death penalty combined with lengthy solitary confinement amounts to double punishment that is both excessive and cruel. Indeed, Kennedy separately queried whether lengthy death-row confinement is consistent with “the purposes that the death penalty is designed to serve,” raising the question of his own accord during oral argument in Hall v. Florida, another case not formally presenting the issue. Ultimately, though, in his refusal to unsettle the death penalty status quo, Kennedy seemed more inclined to gauge the degree of civilization in American society by its prisons than by its execution chambers.