Empirical SCOTUS: One opinion more complex than the next

on Jun 13, 2018 at 3:23 pm

The Supreme Court finally appears decently situated to complete its decision-making for the term. Some holdups are still in play, including the long-since-argued case of Gill v. Whitford. Gill was argued 255 days before the next possible opinion release date of June 14, 2018. Only 10 cases have taken longer to decide since 1946. With 39 signed decisions so far this term composed of over 90 different opinions, the justices have cobbled together opinions of varying complexity. That the justices feel the need to defend their positions is evident from the six decisions with 5-4 voting splits along ideological lines that left the liberals in dissent.

It is one thing to say a case or an opinion is complex. Measuring varying levels of complexity is an entirely different animal. Past papers have used the number of legal provisions and issues as a proxy for case complexity. Another way to observe decision complexity is through elements distinct to each opinion rather than each case. Two basic metrics that shed light on this type of complexity are word count (a topic previously covered by this post) and citation count. Along with these two elements, this post examines components of the citations in each case to further peruse the diversity of justices’ choices within opinions.

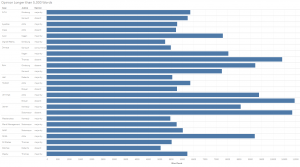

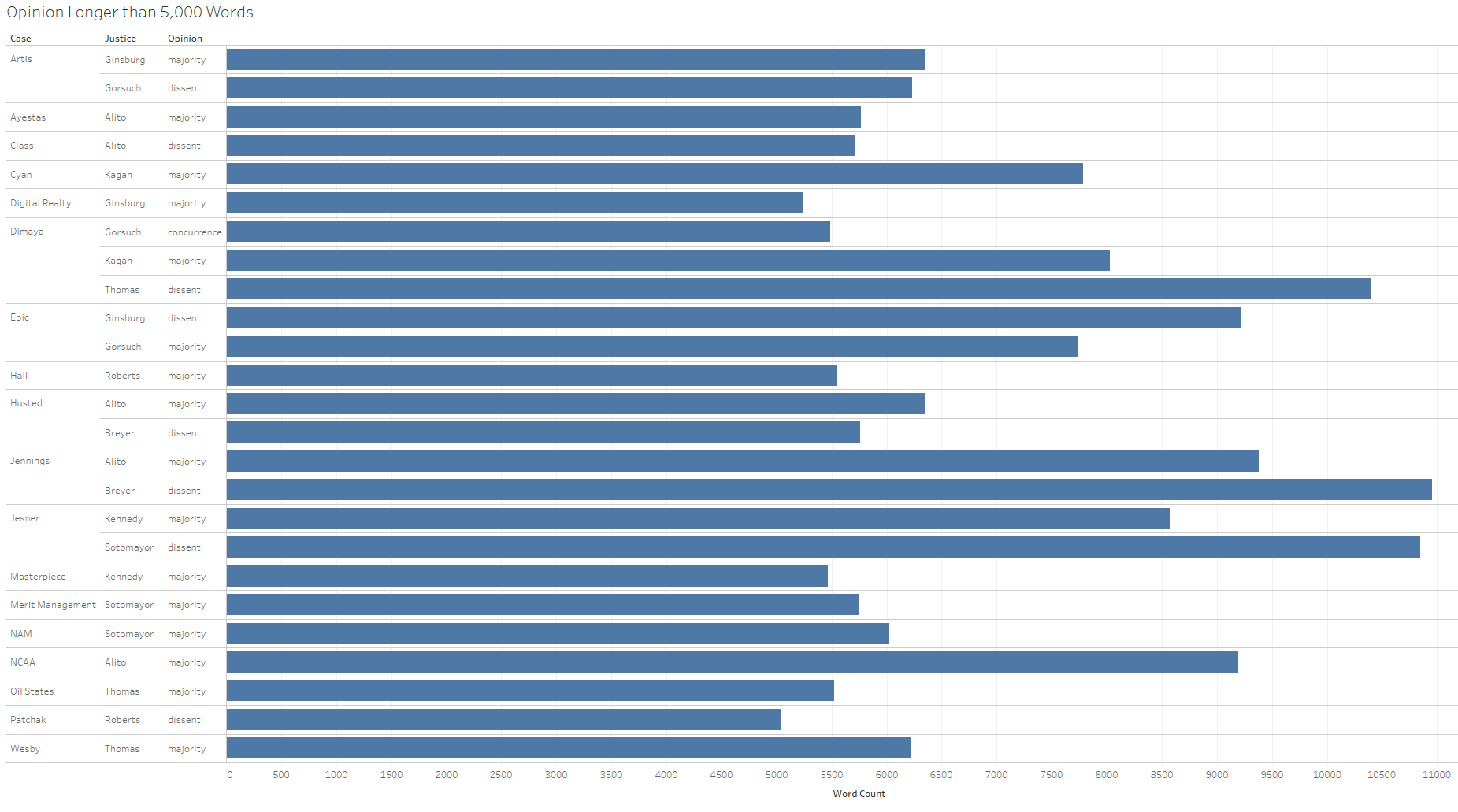

While some justices are naturally inclined to greater verbosity, the justices have each written a fairly similar number of opinions of more than 5,000 words so far this term.

Justice Samuel Alito, although historically not often the justice with the longest opinions, is clearly ahead of the pack of other justices for most opinions lengthier than 5,000 words so far this term. But as University of Washington law professor David Ziff recently pointed out, it is Alito who railed against Justice Stephen Breyer for the length and complexity of his dissenting opinion in Husted.

Alito’s concern over length is a bit perplexing, because his majority opinion is almost 500 words longer than Breyer’s dissent (The lengths of both are shown in the first figure.). Conversely, in 10 instances or over a quarter of the decisions so far this term, a dissenting opinion has been lengthier than the majority opinion. Those instances are shown next.

To be fair to both Alito and Breyer, Breyer’s dissent in Jennings v. Rodriguez, the longest opinion so far this term, was much longer than Alito’s majority opinion in that case.

Opinion length is related to multiple factors. These include the authoring justice’s writing style but also the case facts, the applicable law as the justice sees it, and the justice’s perception of how to respond to other related opinions from the same case and from the Supreme Court’s catalog of precedent. With all of these factors weighing on a justice’s choices when writing an opinion, it should be no surprise that there is actually great variability in opinion length both within this term and across terms. The following figure shows the opinion length distribution for all opinions so far this term.

Although the distribution is clearly skewed to the low end based on many of the justices’ curt separate opinions, many of the opinions are also in the 3,000 to 5,000 word range.

When we look at the justices’ average opinion length by opinion type we can begin to gather an additional sense of the source of variation in relative opinion length.

In general, majority opinions this term have been longer than dissents, which have been longer than concurrences. But the third figure in this post shows that this ordering of opinion types by length is not always consistent.

The notion that the justices personally diversify opinion length is apparent from the variation in length of majority opinions so far this term.

Alito, for instance, not only wrote the longest majority opinion in Jennings and the second longest in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association, but he also wrote the shortest majority opinion in Koons v. United States. Justice Elena Kagan, who has authored some of the lengthiest opinions in recent terms, authored the fourth and fifth longest majority opinions so far this term with Sessions v. Dimaya and Cyan Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund. The highly anticipated decision in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission turned out to fall in the middle of opinion length so far this term with 5,465 words.

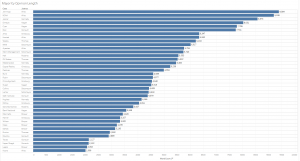

Opinion length only tells part of the story of opinion complexity. A look at the relevant law analyzed in each opinion gives a different perspective on complexity. One way to measure citations is through distinct cites or unique case cites within an opinion. For example, if two citations within an opinion cite the same case, then these are treated as one distinct cite. The opinions this term with the most distinct cites are covered below.

Justice Clarence Thomas’ dissenting opinion in Dimaya far out-cites all other opinions so far this term. The opinion with the next most distinct citations is Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis. Interestingly, 25 opinions so far this term have included at least 25 distinct citations.

Thomas not only cited the most distinct cases in Dimaya, but also cited the most distinct cases in the aggregate so far this term by a large margin.

The extent of the difference in cite counts between Thomas and the rest of the justices connotes the possibility that he has more detailed legal analyses in his opinions this term, although, like most justices, Thomas uses many of his citations as support for positions and does not analyze them in great depth. This count data still do likely present an important gauge of relative clerk workload.

We can also turn this around a bit and look at the cases that have been distinctly cited most often this term.

The case with the most distinct cites to it so far this term is Arbaugh v. Y & H Corp., which deals with the Supreme Court’s proper jurisdiction. While Arbaugh appeared in seven opinions so far this term, several other cases appeared in six, including the court’s decision two terms ago in Bank Markazi v. Peterson, which relates to whether certain statutorily directed judgments pass constitutional muster.

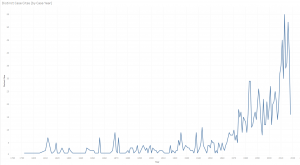

Looking at the number of citations in a case or the number of times a case is cited gives a sense of complexity and case importance. Another metric of case importance has to do with case age. Several empirical papers show an inverse relationship between the age of cases and the frequency with which the justices cite them. With this implication in mind we can look at the age of distinct Supreme Court cites so far this term for consistency with this hypothesis.

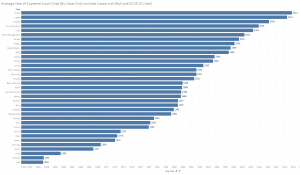

Expectations based on this graph may be that the court tends to cite more recent cases with greater frequency or that older cases that are cited must stand for particularly important positions. The choice of precedent by age is not always an entirely subjective decision, though, as the line of precedent related to individual cases might warrant or require the application of older or newer precedent. The distinctions at the case level are visible in the figure below, which shows the average decision year of Supreme Court cases cited in this term’s opinions.

The 226 years of variation in age for cases cited this term leaves quite a bit of room for older cases to skew the average. That being said, the 59-year spread between the average year of the cases cited in Koons and in Hall v. Hall or Patchak v. Zinke still says a lot about the variation in age of precedent cited in different cases.

This variation is not only visible at the case level but also among justices.

So far this term Kagan and Justice Anthony Kennedy, for instance, have utilized much more recent precedent in distinct cites than either Breyer or Justice Neil Gorsuch. This likely relates to case-specific factors as well as to personal predilections. Looking at case age or year alone hides the substance of the cases that compose these measures. The next two figures look at some of the oldest and newest cases cited in this term’s opinions.

The following figure looks at the number of distinct cites to cases decided on or before 1850.

Another jurisdictional case tops this list — The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon. Schooner Exchange was actually looked at more frequently this term than much more recognizable cases like McCulloch v. Maryland and Fletcher v. Peck. The trailblazing decision of Marbury v. Madison only appeared in one opinion so far this term.

The Supreme Court was quite willing to cite recent decisions in its opinions this term. This includes a cite in Koons to the decision in Hughes v. United States, which the court released the same day. The following figure isolates distinct cites to decisions from the past two years.

Ziglar v. Abbasi, the most-cited recent decision, appeared in Alito’s majority opinion in Jennings, Thomas’ majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Wesby, Kennedy’s majority opinion in Jesner v. Arab Bank, Gorsuch’s concurrence in Jesner, and Thomas’ concurrence in Collins v. Virginia. This term’s decision in Jennings was already cited in Alito’s dissent in McCoy v. Louisiana, Thomas’ concurrence in Husted v. Randolph Institute, Breyer’s dissent in Husted, and Alito’s majority opinion in Murphy v. NCAA. Although more recent precedent played a greater role in this term’s decisions so far, several older decisions have clearly also left their marks.

These measures show varying levels of opinion complexity. They convey potentially different amounts of effort required by particular cases as well as the justices’ willingness to dive into the panoply of the Supreme Court’s historic decisions. Opinion complexity is difficult to establish with an individual measure, but the convergence of multiple measures gives a sense of the combined pressure put on each justice with each opinion, and the self-imposed workload choices the justices have made so far this term.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.