Empirical SCOTUS: Retirement plan blues

on May 23, 2018 at 1:19 pm

It is that time of year again. As we near the end of the Supreme Court term, we are experiencing another round of prognostications on whether Justice Anthony Kennedy will retire, leaving another vacancy for President Donald Trump to fill. (Last year’s take on the possibility of Kennedy’s retirement can be found here.) About this time last year, the headlines ranged from describing the conflicting retirement rumors to exploring the potential effects and dire consequences of such a vacancy. This year pundits on the left and right are forecasting along similar lines.

Kennedy, the second-oldest justice on the Supreme Court at 81 (after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who is 85), is at an age where retirement not only is reasonable but should be expected. This is not to say he will retire this year or anytime in the imminent future. Across the history of the Supreme Court the two oldest justices to leave the court — Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Paul Stevens — did so at the age of 90. (Professor Lee Epstein’s Supreme Court Justices Dataset is a main resource used for justices’ age-related data.) Both retired from the bench. On the other end of the spectrum, Justice Benjamin Curtis was the youngest justice ever to retire at the age of 47, in 1857. Focusing on justices who joined the Supreme Court after the beginning of the 20th century, Justice Wiley Rutledge was the youngest justice to depart the court, as he died while still a member of the court in 1949 at the age of 55. Justice William Moody was the youngest to retire after the beginning of the 20th century, at the age of 56 in 1910.

Fifty-five justices have retired from the Supreme Court since it was established in 1789 and 35 justices have retired since 1900. For this group, the average age at retirement is 73.6, or between seven and eight years younger than Kennedy’s current age. This all goes to show that Kennedy’s departure would hardly be unexpected based on the court’s history.

To probe a bit deeper, how better to get a sense of the likelihood that Kennedy will depart than by looking at previous retirees? Nine justices retired between and including Chief Justice Warren Burger in 1986 and the most recent retirement of Stevens in 2010. The figure below looks at three timelines that track when these nine justices joined the court, retired, and, where relevant, passed away.

If Kennedy were to retire at the end of this term, his placement on such a timeline would not look anomalous.

The retirees can be split along many different dimensions. One fault line used in this post is between “contented retirees” and “discontented retirees.” Although both types of justices may retire, a justice’s relative contentment, the immediacy or urgency of their intended retirement and their perception of the balance of the court upon their departure may heavily influence a justice’s decision.

Disagreement measures

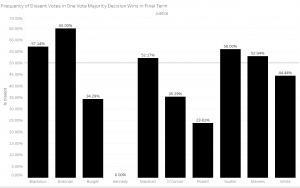

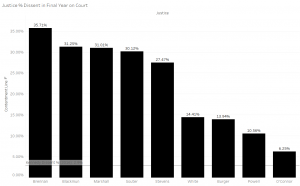

According to individual disagreement measures, Kennedy should be quite satisfied with his place on the Supreme Court. The measures that convey this are his dissents in cases decided by one vote and his dissenting frequency last term. (The last term prior to retirement is used for all other justices.)

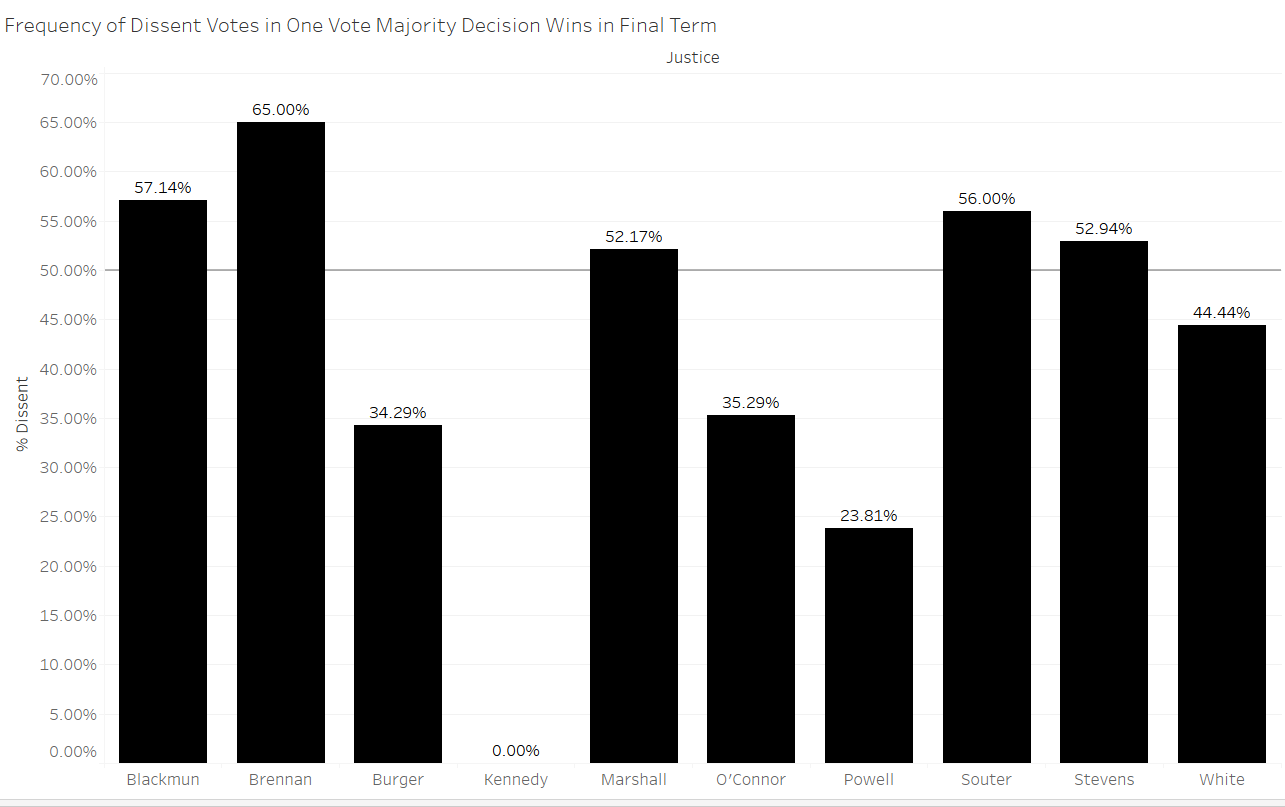

The first indication that Kennedy should be satisfied with his place on the Supreme Court comes from his lack of dissents in cases decided by one vote last term.

As with much of the data on the retirees, there is a clear distinction between liberal and conservative justices. Because conservatives have been in the majority on the Supreme Court since the early Burger court, all of the justices examined in this post retired from a court with a conservative majority. The liberal-voting justices in the figure above dissented more than 50 percent of the time in cases decided by one vote in their final terms, while the more conservative justices are all below the 50-percent line. Kennedy’s zero percentage reflects that he did not dissent in a case decided by a one-vote margin in the 2016 term, the last complete term available for this analysis. However, he has already dissented in two such cases during the 2017 term – Sessions v. Dimaya and Artis v. District of Columbia.

The second measure is overall dissent frequency. So far this term Kennedy has dissented four times, or in about 13 percent of the signed decisions. Based on last term, though, his dissent frequency was also lower than any of the last nine retirees in their final full terms.

Similar to the previous figure, there is a large disparity between the justices on the conservative and liberal ends of the spectrum. Although Kennedy’s frequency dissenting across the 2016 term is far below any of the justices pictured above, his current frequency for the 2017 term is in line with the dissent frequencies of the four more conservative justices.

Agreement measures

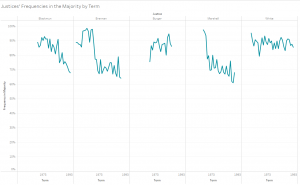

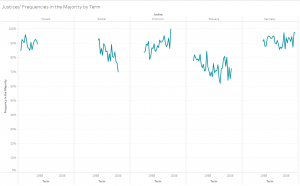

The second set of analyses looks at the question of contentment from the opposite perspective — that of how well the justices agreed with the court’s majority. Kennedy has been one of the court’s most frequent members in the majority over the last several terms.

Kennedy’s frequency in the majority has hovered at about the 90 percent level across his career on the Supreme Court. The more liberal justices’ frequencies tend to fall well below this marker, while the more conservative justices are all in a similar range.

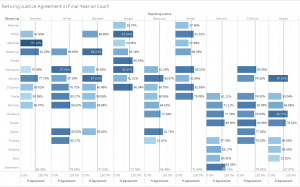

Looking at the retiring justices’ agreement levels with the other justices on the court in their final terms shows a similar distinction between more and less contented justices. Note that the darker bars in the figure below correspond with higher agreement levels and the gray lines are the retiring justices’ average agreement levels for the term.

Justice Byron White had the highest average agreement level at 78.66 percent. Similar to the previous figures, the more liberal justices in this figure are all below the 70-percent average agreement level, while the more conservative justices’ levels are all above the 70-percent mark. Per SCOTUSblog’s statistics for the 2016 term, Kennedy agreed with all justices aside from Justice Clarence Thomas at least 80 percent of the time.

Political climate

If justices are concerned with the potential consequences of their retirement and the future direction of the court, they may care about specific retirement timing. This theory, known as strategic retirement, posits that justices care about the president in office when they retire because the president ultimately makes the decision on whom to nominate to fill their seat.

Two aspects that might play a role in the justices’ decisions are whether their policy preferences accord with those of the sitting president and whether the public has a favorable view of the president.

Professor Michael Bailey’s data bridge presidents’ ideology scores with those for Supreme Court justices. These data, which go through the 2007 Supreme Court term, provide additional insight into the justices’ strategic decision-making. The figure below looks at the absolute difference between the appointing president’s ideology and the justice’s ideology in the first year on the court and then between the president’s ideology upon their departure and the justice’s ideology in their final term on the court. The most important calculation here is the difference in relative ideology upon retirement.

Most justices in the figure above retired with low relative absolute differences in ideology scores. Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had the highest difference in score upon his retirement, was already in declining health when he left the court and was primarily a member of the court’s dissenting coalitions at that time. Even though Stevens and Justice David Souter do not have available scores for the years of their retirements, both tended to vote on the liberal end of the spectrum and retired under President Barack Obama, and so neither would likely have had a great absolute difference in ideology from the president upon their retirements.

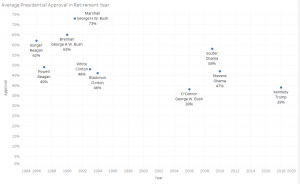

A final measure looks at the president’s approval rating at the time of the justice’s retirement as a marker of a president’s strength in office, which may influence a justice’s retirement decision timing. The approval data comes from the UCSB Presidential project and is averaged across the president’s approval rating for the justice’s last year on the court. (The data for Kennedy is Trump’s average approval so far in 2018.)

If Kennedy were to retire right now, he would retire under the second-lowest average presidential approval level for the justices measured in this post. Only President George W. Bush’s approval rating in 2006 was lower. The rest of the justices retired under presidents with at least a 40-percent average approval rating in the justice’s final year, suggesting a potential albeit tenuous relationship that may factor into a justice’s calculus.

Some justices don’t have the luxury of choosing when to retire, while others can be more strategic about their decisions. Going back to the first figure in the post, Marshall passed away merely two years after retiring, which shows that even if he had not retired when he did, he would not have been an active member of the court for much longer. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor would have retired earlier than she did to take care of her ailing husband had Chief Justice William Rehnquist not passed away. Others like Souter who retired at an early age could be more cautious about when and in what political environment to retire. Right now, as far as we know, Kennedy is in good health (although as this report from Fix the Court indicates, the justices are often not transparent with their current health statuses).

If we presume that contented justices in good health are more likely to stay on the court, especially when their ideologies do not correlate with those of the incumbent president, then signs point to Kennedy remaining on the court past this term, notwithstanding all of the discussion surrounding his retirement (assuming Trump’s views do not align with those of Kennedy). Kennedy might also be wary that the center of the court will almost assuredly shift to the right if he leaves at the end of the term. Although, based on his age and tenure on the court, Kennedy is not likely to remain on the court much longer, the data suggest he may stay put for now.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.