Ask the author: “We the Corporations”

on May 15, 2018 at 2:25 pm

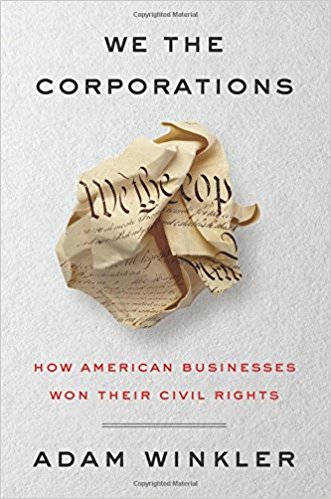

The following is a series of questions posed by Ronald Collins to Adam Winkler on the occasion of the publication of Winkler’s book “We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights” (Liveright, 2018, $28.95, pp. 471).

Adam Winkler is a professor of law at the University of California at Los Angeles. His last book was “Gunfight: The Battle over the Right to Bear Arms in America” (W.W. Norton, 2011).

Welcome, Adam, and thank you for taking the time to participate in this question-and-answer exchange for our readers. And congratulations on the publication of your latest book.

* * *

Question: Your book offers a new wrinkle on the founding of America and the Jamestown story of 1607. Do tell.

Winkler: Americans celebrate the liberty-seeking Pilgrims, but the first permanent English colony in the New World was 13 years earlier in Jamestown, which was a corporate business venture. Indeed, the Virginia Company came to America to make money. The company also introduced democratic reforms, such as the first representative assembly, not in the spirit of popular sovereignty but to pursue profit.

Question: How do dissent in the colonies and the Boston Tea Party of 1773 fit into your narrative?

Winkler: The American Revolution was also in small part a revolt against the world’s most powerful corporation, the East India Company. When the company’s fortunes soured, the British government deemed the corporation too big to fail — and, as part of a massive bailout, gave the company for the first time the right to sell tea in the colonies without American middlemen. The Boston Tea Party was an uprising by merchants who, that night, went out to throw the East India Company’s tea overboard.

Question: The way you tie all the conceptual dots together in your examination of corporations and the Constitution is impressive. One of those dots is Chief Justice John Marshall’s 1809 opinion in Bank of the United States v. Deveaux. Why is that case important?

Winkler: Decided a half century before the first Supreme Court cases on the rights of African Americans and women, Bank of the United States v. Deveaux was the first Supreme Court case on the rights of business corporations under the Constitution. The Bank of the United States, the nation’s largest and richest corporation, won the right to sue under Article III diversity jurisdiction, even though the text refers only to “citizens.” The case, which laid the foundation for two centuries of corporate-rights cases to follow, is one of the neglected landmarks of American constitutional law.

Question: Your book exposes a misleading argument presented to the Supreme Court by a railroad lawyer in the 1885 case San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company. Tell us a little bit about that disingenuous argument and how it played out in that case.

Winkler: In the 1880s, the Southern Pacific Railroad Company launched a remarkable series of what its lawyers called “test cases” — more than 60 in all — to win expansive rights for corporations under the 14th Amendment. Two of those cases made it to the Supreme Court. In the first, the railroad’s lawyer, Roscoe Conkling, who had been one of the drafters of the 14th Amendment, told the justices the provision was written to protect not just the freed slaves but also business corporations. He even produced a musty old journal that he said was a never-published record of the drafting committee’s deliberations. The journal was real, but historians who looked into the case years later quickly realized that the amendment had never been revised in the way Conkling claimed. As Howard Jay Graham, one of the leading historians on the 14th Amendment, concluded, Conkling had engaged in “a deliberate, brazen forgery” to win new rights for corporations.

Question: The following year the Supreme Court decided Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company. This time the inaccurate work was done by the court’s Reporter of Decisions. Who was that man and how did his handiwork shape the history of American constitutional law?

Winkler: Another of the Southern Pacific’s test cases reached the Supreme Court, but the justices declined to rule on the constitutional question, leading the colorful Justice Stephen Field to complain about the omission in a separate opinion. Then the case took a bizarre turn. The Reporter of Decisions, J.C. Bancroft Davis, included a headnote in the official published version of the opinion saying the court had held corporations were covered by the 14th Amendment. A few years later, Field, who was rumored to carry a gun beneath his robes and remains the only sitting justice ever arrested for a crime (and the charge was murder, no less), seized upon Davis’ headnote. In a majority opinion on a separate issue, he wrote that the court had held that corporations had 14th Amendment rights in the Southern Pacific case — something he clearly knew to be untrue.

Question: There is a fascinating discussion in your book about the 14th Amendment cases that were decided by the Supreme Court between 1868 and 1912. What happened?

Winkler: Once the Supreme Court extended 14th Amendment rights of equal protection and due process to corporations, businesses flooded the courts with constitutional challenges. The ensuing years would be known as the Lochner era, when the court broadly read the Constitution to protect business. Meanwhile, in cases like Plessy v. Ferguson, the justices refused to read the 14th Amendment to provide any meaningful protections for minorities. By 1912, the court had heard only 28 cases on the 14th Amendment rights of African Americans — and an astonishing 312 cases on the 14th Amendment rights of corporations.

Question: During the Lochner era (1897-1936), the Supreme Court bifurcated the constitutional rights of corporations. What did it do and why?

Winkler: Even though famously friendly to business, the Lochner-era Supreme Court also imposed new boundaries on the constitutional rights of corporations. They had property rights but not liberty rights. Government could not seize corporate property without just compensation. But corporations did not have rights tied to bodily integrity, political freedom or personal conscience. A century before Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, courts universally upheld campaign-finance restrictions on corporate money. In 1907, the Supreme Court in Western Turf Association v. Greenberg held that corporations holding themselves out to the public did not have a constitutional right to refuse service to unwanted customers — a case with more than a passing resemblance to this term’s Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission.

Question: What was the Michigan Supreme Court’s 1919 ruling in Dodge Brothers v. Ford Motor Company and why is it an important part of your story about corporate rights and wrongs?

Winkler: When Henry Ford raised wages and reduced dividends, the Dodge brothers, who were early investors already made enormously wealthy from their investment in Ford’s car company, sued to stop him. They won a landmark ruling that declared corporations were to be run in the interests of shareholders, not employees or customers. Just as corporations were winning more of the rights of people in constitutional law, corporate law was dictating that corporations value profit over all — that corporations become, as Kent Greenfield details in a terrific new book coming out this fall, less like people.

Question: Not long before he was nominated to the Supreme Court, Lewis Powell prepared a memorandum for the Chamber of Commerce. Tell us about that.

Winkler: Months before his nomination, Lewis Powell wrote a memorandum to the Chamber of Commerce outlining how the left threatened capitalism and calling for corporations to fight back aggressively. The chamber followed Powell’s advice, and his letter is often credited as influencing the business backlash of the late 1970s and 1980s. On the Supreme Court, Powell turned his memorandum into law, writing First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, which held that corporations had the First Amendment right to spend their money on politics three decades before Citizens United. The book tells the story of an amazing multi-media sendoff Philip Morris gives for Powell, a longtime board member who was leaving to join the court. At the end, Powell is called up to the stage where he ceremoniously receives his judicial robes, bestowed upon him by the chief executive of the tobacco giant.

Question: You write that Ralph Nader and Alan Morrison “developed an innovative and influential theory of free speech that ultimately helped commercial speakers.” How so, and what did they see as the limits of their theory?

Winkler: Representing consumers, Nader and Morrison’s Public Citizen Litigation Group challenged a Virginia law banning pharmacists from advertising drug prices. Because their clients were the consumers, Nader and Morrison argued the ban infringed the rights of the listeners regardless of the speaker’s rights. The Supreme Court agreed, adopting their innovative “listeners’ rights” theory of the First Amendment — and that same theory would be used in Citizens United to justify invalidating restrictions on corporate spending. Moreover, Nader and Morrison’s case also resulted in the commercial-speech doctrine, which has been used primarily by businesses to fight against laws designed to help consumers.

Question: You offer a nuanced look at Justice Anthony Kennedy’s 2010 opinion in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. Say a few words about that.

Winkler: For all the controversy over Citizens United and corporate personhood, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion for the Supreme Court never endorses nor relies upon the idea that corporations are people. Instead, Kennedy refers to corporations as “associations of citizens.” This is exactly how the Supreme Court has usually understood corporations over American history. In corporate law, personhood means the corporation is its own independent entity, with rights and duties wholly separate from those of its members. In expanding corporate rights, however, the court has often rejected corporate personhood and based the rights of corporations on the rights of their members.

Question: For purposes of First Amendment free-expression law, do you think the Supreme Court should distinguish between for-profit corporations (e.g., Exxon) and nonprofit corporations (e.g., the NAACP)?

Winkler: One of the surprising things I discovered in researching the rich history of the struggle for equal rights for corporations was that the Supreme Court has rarely differentiated between different types of corporations. Cases involving “corporations” that were not businesses, including Dartmouth College, the NAACP, and even Citizens United, all nonetheless established important precedents that helped for-profit companies. Another potential distinction is between media corporations, which won early and influential First Amendment cases like Grosjean v. American Press Company, and other corporations funding speech.

Question: What do you see as the next likely constitutional frontier that litigation on behalf of corporations will attempt to conquer?

Winkler: One pressing corporate-rights issue is the ability of businesses to use the Constitution to win exemptions from generally applicable laws, like antidiscrimination laws. In 2014, Hobby Lobby Stores Inc. used religious liberty under a federal statute to win the right to refuse to comply with a law requiring businesses to insure birth control in employee health plans. The Masterpiece Cakeshop case this term could establish a right of public businesses to deny service to LGBTQ customers. And, of course, corporations are very active in First Amendment litigation; businesses and trade associations bring nearly half of all free-speech challenges filed in the federal courts today.

Question: One final query: On the one hand, there is something rather shocking in your account of the historical rise of corporate rights, especially on the constitutional front. On the other hand, it might also be seen as an inevitable development in a highly capitalistic culture. If so, it seems that the decisive factor here is the culture, not the corporation. What are your thoughts on this?

Winkler: Culture is important, but so are structure and law. Despite our mythology of blind justice, the courts are a forum that favors corporations. Unlike the historically underfunded civil-rights and women’s-rights movements, the corporate-rights movement’s clients could afford to hire the best lawyers and pursue expensive, risky, cutting-edge lawsuits. We think of the Supreme Court as a bulwark for the protection of politically powerless minorities but, as the story of corporations winning constitutional protections highlights, the court has often used its power to protect the wealthy and the powerful.