Argument preview: Does no suit mean no suit?

on Nov 6, 2012 at 2:04 pm

At 10 a.m. Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hold one hour of oral argument on Already, LLC v. Nike, Inc. (11-982), a trademark dispute over sneaker design with the focus on federal court authority to rule on a mark’s validity. Arguing for sneaker producer Already will be James W. Dabney of the New York office of Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson, with twenty-five minutes of time. Representing Nike, also with twenty-five minutes of time, will be Thomas C. Goldstein of the Washington law firm of Goldstein & Russell. Between the two of them, representing the federal government, with ten minutes of time to argue that the case should be sent back to the lower courts for further review, will be Ginger D. Anders, an Assistant to the U.S. Solicitor General.

Background

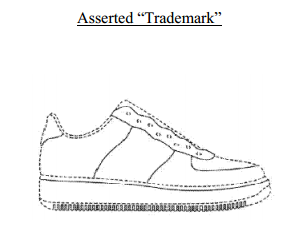

Few items on Americans’ shopping list are as popular as sneakers and, for some consumers, the brand name might be as important as how the shoe fits. Such a label can itself be a valuable status symbol, and it is thus worth protecting against would-be imitators. The big sports goods company, Nike, Inc., is diligent about protecting its trademarked products, and that includes its very popular low-cut sneaker design, “Air Force 1,” which sells in the millions every year. Nike in 2008 registered a trademark on that design, giving it an exclusive right to make and market that item with its particular look. It has been producing that shoe since 1982.

One way that a trademark owner can protect its mark is to sue a competitor, claiming that it is illegally copying the protected design or product. Nike did that. But there is another way, and that is what is at issue before the Supreme Court now. The trademark owner can move strategically to keep its mark intact, if a legal threat to its continuing validity arises. That is what Nike also did.

Nike’s trademark for its “Air Force 1” shoe covered the stitching on the outside, the design of the panels on the outside, the design of the eyelets for the laces, the design of a vertical ridge pattern on the sides of the sole, and the placement of those features in relation to each other. In late 2009, Nike discovered that another sneaker company, Already LLC, had hired two of Nike’s shoe engineers, and was producing shoes under the name “Yums.” In July 2009, Nike sued, contending that Already was selling shoes under the names “Sugar” and “Soulja Boy” with what Nike’s complaint called “a confusingly similar imitation” of “Air Force 1.” “Yums” sneakers were selling quite well, too.

One way that a company like Already can defend itself is to file an answering claim of its own, contending not only that it is not infringing on trademark rights, but — more importantly — arguing that the trademark is not valid, after all, and should be cancelled. That is what Already did in November 2009. The case was now set for review in a federal district court, with the commercial fortunes of both companies significantly at stake.

At that point in this dispute, there was, of course, a live controversy between the two companies. That is of fundamental importance, because no federal court has any authority to decide anything brought before it if the dispute is not a “case or controversy,” as Article III puts it. After suing, Nike and its lawyers decided that Yums shoes were not much of a threat after all. Some major department stores and sneaker retailers were not offering Yums, and the last significant one that did — Finish Line — stopped doing so in April 2010.

As Nike’s lawyers would later tell the Supreme Court, “in light of these developments, Nike concluded that [Already’s] activities were no longer significant enough to warrant the cost of litigation.” So, Nike extended to Already a promise that it would not sue — what lawyers call “a covenant.” Nike said it was attaching no conditions to the promise, and that it was “irrevocable,” and that the company was giving up “any action in law or equity” against Already.

Already would tell the Supreme Court that Nike had “abruptly delivered a document styled ‘Covenant Not to Sue.'” And, the competitor noted, Nike promptly asked the federal court to dismiss both sides of the court case, Nike’s and Already’s. From Nike’s perspective, there was no longer a “case or controversy,” so the district court had lost its jurisdiction to decide the case — including, of course, Already’s claim that the “Air Force 1” trademark was not valid.

Nike won that argument in the district court. Although Already had a legal right to ask the federal Patent and Trademark Office to cancel the Nike trademark, it did not do so, perhaps in part because the PTO had given Nike the trademark at issue. Instead, it decided that the better option was to try to persuade the Second Circuit Court to revive its counter-claim against that trademark. The company said in court filings that it was concerned that Nike’s lawsuit against it had harmed its commercial reputation, and was deterring investors from putting or keeping money in Already. And, it contended, the promise not to sue would not protect Already’s reputation, and was inadequate, anyway. The Circuit Court ruled for Nike, finding that the promise not to sue had resolved the infringement lawsuit, and thus had taken away the district court’s jurisdiction to decide Already’s plea to cancel the Nike trademark.

Petition for Certiorari

Already’s lawyers took the case on to the Supreme Court last February. No longer a marketing dispute about sneakers, the case was now a constitutional dispute about whether a court’s powers under Article III could be lost, at least in a trademark dispute, if the owner of the mark promised not to sue an alleged infringer. Because the scope of federal jurisdiction was a constitutional matter, the petition noted, this dispute could not be settled by Congress’s enactment of new legislation. It was up to the Court to decide.

The Yums company contended that Nike had used its promise not to sue to manipulate the federal courts, and to cover up the weakness of its claim to trademark rights. It said: “When the validity of a federally registered trademark is challenged in a federal court action, the registrant [the trademark owner] may have a strong motivation to try and prevent the court from reaching the merits of the validity issue. This motivation may be especially strong where a claimed trademark is a product configuration whose eligibility is highly suspect.”

If that strategy works, and the case is brought to an end, Already asserted, the trademark owner keeps its registration and can “continue to assert it in the future” against anyone, including a challenger like Already if it goes beyond the specific marketing activity that led to the infringement claim in the first place. The petition contended that the federal appeals courts were divided on the underlying Article III issue in the trademark context, at least if the promise not to sue is delivered after the lawsuit in federal court has begun. The Ninth Circuit Court, Already contended, had held that a covenant not to sue over trademark infringement must eliminate every risk of a potential future lawsuit — a standard that Already contended had not been met in the Nike case.

Nike opted not to respond to Already’s petition, but the Supreme Court asked for its views on April 4. Nike began its brief in opposition by defending the scope of its covenant not to sue, disputing Already’s characterization of it as applying only to Already’s commercial activities at the time Nike sued. The promise, Nike said, “was worded to include future sales,” and specified how free Already would have been to make and sells its Yums. The Circuit Court, the document said, had focused on that specific wording, and “it could not conceive of a potentially trademark-infringing product” that Already might produce that would not be protected by the covenant.

Nike’s filing also disputed that there was any dispute among the lower courts on the standard to be used to determine whether a promise not to sue was sufficient to put a stop to a lawsuit. The Ninth Circuit decision relied upon by Already, Nike said, depended upon a conclusion that the covenant at issue there was “incomplete and qualified.”

If Already were truly intent on challenging the validity of Nike’s “Air Force 1” trademark, Nike’s response said, it had the option of going to the PTO with a challenge, and it did not do so. Instead of doing that, Nike said, Already was trying to draw the Supreme Court into a fight that was only about the specific facts of this dispute — a point that Already sought to dispute in a reply brief.

Briefs on the merits

Already’s brief on the merits put particular emphasis on the fact that Nike had not moved to scuttle the lawsuit until after the case was in court, and Nike was facing a challenge to the validity of a mark that Already has insisted is undeserving of legal protection. The brief was careful to quote Already’s attorney as having told the district court that “I don’t think that there could be two more different appearing products in the marketplace” than Yums and Air Force 1.

On the jurisdictional issue, Already’s brief pointed out that the district court had jurisdiction of the case and had the clear authority to rule in Already’s favor to cancel the “Air Force 1” mark, so Nike had moved to divest the court of power that it already had. And, the brief went on, Nike was completely unable to show that the continuation of its trademark would not inhibit other producers of sneakers that Nike feared as competitors. The Nike trademark keeps out of the public domain even sneaker producers who would not actually imitate Nike’s design, but could be accused of doing so.

If a trademark registrant can always end a challenge in federal court by issuing a covenant not to sue, like the one Nike sent to Already, the brief argued, such a trademark would remain on the government’s register as nothing more than a “scarecrow” that harms both would-be competitors and the consuming public.

Already had the support of the Public Patent Foundation and of a group of professors of intellectual property, both of which filed an amicus brief on that side. The Intellectual Property Owners Association filed a brief that was said to be neutral, urging the Court to adopt a balancing approach when a holder of intellectual property rights seeks to end a court case against it.

Nike’s brief on the merits emphasized the reach of its promise not to sue, saying that Already’s attempt to scuttle the “Air Force 1” trademark could be a live controversy in constitutional terms “only if Already is threatened with concrete harm.” Under the covenant, it added, there is no “reasonable prospect of any controversy” arising between the two companies — over past, present, or future sneaker marketing activity.

The brief suggested that Already would have a claim in the future only if it were able to show that it has a plan to market a shoe that is outside of the scope of the covenant. It has made no such claim, and does not insist even now that it has any such plan, Nike said. There is simply no dispute between these two companies that goes beyond the specific terms of the covenant, according to the Nike brief.

Moreover, Nike contended, the attempts by Already to show that investor interest in it has dried up, or will, are speculative and unconvincing, especially in light of the broad sweep of the covenant not to sue.

And, it added, Already cannot salvage its lawsuit by arguing that Nike cannot end a case by changing Nike’s conduct as a litigant. What Nike’s conduct shows, according to its brief, is that it has vowed that it would not sue Already in the future for any marketing activity that Already might contemplate. “There is no realistic prospect of Nike returning to its conduct that gave rise to this dispute by enforcing the mark against Already,” the filing argued. It is simply “fanciful,” Nike contended, that it will continue in perpetuity to make “strategic use of covenants” to protect its trademark. If there were any proof of bad faith in this case, Already would have been eligible to recover its attorney’s fees and its costs, and the district court explicitly refused to make such an award here, Nike noted.

Lining up in support of Nike as amici are the International Trademark Association and the American Intellectual Property Law Association, and two companies that are owners of popular trademarks — Levi Strauss & Co. and Volkswagen Group of America, Inc.

The federal government, including the Patent and Trademark Office, has stepped into the case at the merits stage, not in support of either side but in a way that partially could help either side. The case, the federal brief argued, should be judged under the standard of whether “the voluntary cessation” of conduct by one side is sufficient to bring a lawsuit against it to an end. The standard under that approach, the brief said, is whether Nike can show whether its covenant not to sue makes it “absolutely clear” that a real dispute between it and Already “could not be reasonably expect to recur.”

The lower courts, the government document said, did not require Nike to meet that test. Moreover, it added, “the scope of the covenant and petitioner’s [that is, Already’s] planned business activities are unclear.” So, it contended, the Justices should vacate the Second Circuit decision and order it to apply the recommended test. What Already actually plans to do in the future, the brief said, is something that only Already knows, and so it should be put to a test of whether it plans to do anything that would not be protected by Nike’s covenant.

In Nike’s favor, the government brief argued that Already was wrong in contending that trademark owners should not be allowed to use covenants not to sue to head off a trademark invalidity lawsuit. The inquiry on this point, the brief said, should be confined to the two parties actually involved in the case, not third parties that are not within the scope of a promise not to sue. In a final point, the government suggested that, even if the case is not moot, it would be up to the district court to use its discretion to end the case anyway.

Analysis

Nike probably goes into this case before the Court with a slight advantage: this is a Court that tends to be quite strict against keeping cases in federal court, under the Constitution’s Article III, when there are good reasons to have them dismissed. The “standing” doctrine, and that is at the core of this dispute between Already and Nike, is generally being interpreted narrowly by the current majority, so the burden seems to fall most heavily on Already to show there is an ongoing dispute of genuine consequences.

The fact that Already attempted without success to show in lower courts that there was something beyond the covenant not to sue that would keep the dispute alive works against it before the Justices. Even so, the Justice Department/PTO entry into the case, suggesting that Already get another chance to make that same point with additional facts, may well have rescued the maker of Yums from an outright defeat at this stage.

On the legal point, about whether Nike actually was trying to manipulate Article III jurisdiction for its own commercial advantage, it appears that at least some of the Justices had that suspicion, and that is why they granted Already’s petition to have a closer look. Nike has tried in its filings to dispel that suspicion, but Already may have succeeded in keeping some life in it — especially if its lawyers find a way to prove that the company has aspirations to become again a genuine competitive threat to Nike.

(Disclaimer: Nike’s lawyer in this case, Thomas C. Goldstein, is the publisher of this blog, in addition to his role as an advocate before the Court. The author of this post, however, operates independently of the Goldstein & Russell law practice, and Mr. Goldstein had no role in the writing or editing of this post.)